Guest essay by Andrew Sottile

I was driving away from Boothbay Harbor along

River Road, a windy, crowned cutoff, toward Damariscotta, another small

township off Maine’s coastal Route 1. I’d called the bookstore there, which had the text I was after, a history of Maine’s lobster fishing culture, an

acclaimed nonfiction narrative. Maine’s answer to

The Perfect Storm, I figured

. Or better yet, something like

Into

the Wild. I was going to be an adventure writer. This is what I’d told

myself. The next Junger, a younger Krakauer, the reviewers would say. I’d been working on a magazine feature, a profile of Boothbay’s lobster industry. I

conducted interviews, poured over library books and microfiches, even arranged

myself a lobster boat ride on which I nearly fell asleep on my feet from the

dreaded side effects of Dramamine. I had hours of voice recordings—the thick

drawls of lobster fishermen and quantitative theories of marine biologists—but

no real story of substance.

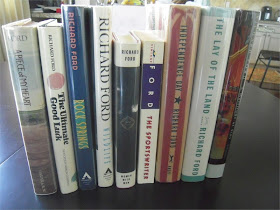

In the front lobby of the Damariscotta

bookshop—Maine Coast Books, it’s called— a whiteboard sign read,

Richard Ford, Tonight at Skidompha Library. Taped

to the sign was a photograph of this Ford character, a black and white author

shot. Gray eyes. Gleaming forehead. And next to the sign were stacks of books.

The Sportswriter I’d heard of.

Independence Day, too. They were about

New Jersey, a place I’d never been and whose residents I resented for staking

summer claim on this beloved northern New England coast. I picked up a

yellow-spined copy of

Rock Springs, its

cover showing a lone mailbox and a vast expanse of prairie—I’d never seen

this one before—and flipped to the first page and read the title story’s first lines:

“Edna and I had started down from Kalispell, heading for Tampa-St. Pete where I

still had some friends from the old glory days who wouldn’t turn me in to the

police.” Then I thumbed forward: “This is not a happy story. I warn you.” I sat in a vinyl-cushioned chair by the window—arrested by the voice, the

frankness, how

real these stories

seemed. I read on. An hour passed. Then another. By now it was nearly seven

o’clock. I purchased the collection with a swamp-ass-soaked twenty, and made my

way to the library next door, where Ford spoke and read from a work-in-progress

and mentioned his very own Boothbay

home, which gave me a thrill. When he was through I shook his hand, said we had

a place near Boothbay, too, and asked about how he writes short stories. I wanted

to know about his approach. “Oh, just write them,” he said. “That’s all you can

do. Just write them.”

I finished

Rock Springs a day later. And if you’d asked me why those stories

made my face feel numb, what about the first-person voices captured me, or how

the narrative structures made them seem truer than any fiction I’d read before,

I couldn’t have told you. All that needed time to steep.

Ford’s short story “Optimists” opens with this sentence: “All

of this that I’m about to tell happened when I was only fifteen years old, in

1959, the year my parents were divorced, the year when my father killed a man

and went to prison for it, the year I left home and school, told a lie about my

age to fool the Army, and then did not come back.” Ford gives his plot

away and reveals what is presumably all the story’s incidents.

His new novel

Canada opens similarly: “First, I’ll tell about the

robbery our parents committed. Then about the murders, which happened later.

The robbery is the more important part, since it served to set my and my

sister’s lives on the courses they eventually followed. Nothing would make

complete sense without that being told first.” These openings,

as Ford has said, “spill the

beans.” He even

told an interviewer he found

Canada’s opening “an irresistible hook.” But

there’s more at work here, something more covert. Ford doesn’t just give away his

story arc; he also creates temporal texture. Both voices establish themselves

as distanced from the stories’ events, which is to say that the passage of time

is obvious in the narrative. Because Ford’s narrator says, “when I was only

fifteen,” the reader understands this story happened long before the actual

telling takes place. And in

Canada, by

referring to lives and “the courses they eventually followed,” Ford implies

that those paths, courses and lives have changed and passed and are now

someplace else, a place different from the story’s setting—in both time and

place.

Ford takes a risk, giving away these climactic

events so early on, yet his stories remain tension-packed. In

Rock Springs’ “Optimists,” for

example, he sets the eventual murder scene with this foreboding sentence: “It

was on a night that Penny and Boyd Mitchell were in our house that trouble came

about.” The line serves as a reminder that the narrator, Frank, has lived

through the story’s events. Then the in-scene story begins. When his

father gets home from work, the narrator says, “I have never seen a look on a man’s

face that was like the look on my father’s face at the moment. He looked wild.

His eyes were wild.” Most important here is that the in-scene character

does not know

why the father is

wild-eyed; neither does the reader. It eventually becomes clear that the father

“saw a man be killed tonight” And when houseguest Boyd Mitchell hostilely

suggests that the father “should’ve put tourniquets on” the dying man, the

reader begins to understand this scene will not end well. Boyd Mitchell will,

of course, lose his life by the hand of the narrator’s father. And while the

narrator ultimately knows this outcome, his in-scene character lacks privilege,

obviously doesn’t know the consequences of the events, or even the events

themselves as they are about to take place. Ford plays with classical dramatic

irony—that is, the discrepancy between what readers know and what characters

know. His readers become more informed, more privileged than the characters

themselves. As Ford

puts it, “I didn't think giving the events away was a risk, but created

its own suspense.” We feel the tension mostly because Ford frontloads

his opening lines.

Many years later, in

Canada, Ford uses charged details to

achieve similar narrative tension. After his parents commit a bank robbery, for

example, the narrator, Dell Parsons, and his sister, Berner, take a ride around

town with their father. Dell finds a packet of money in between the cushions in

the backseat. This detail obviously carries its own feeling of mystery, but

because Ford has already mentioned the robbery, we understand that it did, in

fact, take place at the “

Agricultural

National Bank, Creekmore, North Dakota,” as the money packet indicates.

Now the robbery, and all its baggage, has come back to Great Falls.

Dell’s discovery opens up a whole world of tension in the short car ride. The

reader knows more than Dell does. “I was astounded,” Dell narrates. “I said

‘Oh,’ loud enough to make my father instantly look at me in the driver’s

mirror… ‘Did you see the goddamn cops?’ my father said.” The anxious mood

in the car and the emotions of its characters become obvious—Dell’s fear and

confusion, the father’s paranoia.

Later (and more simply crafted) on their

drive, they pass “the back of the Cascade County jail.” When reading that

line, knowing with certainty the car’s driver, the narrator’s father, will soon

be a resident there, I can’t help but imagine the inside, the gray cells, the

stale light, the cold bars. But here, in this scene, those details are implied

as part of the subtext; the actual jail doesn’t appear until much later—when,

of course, Dell’s parents end up there.

When Gustav Freytag published

Technik des Dramas in 1863, he gave

language to an ancient plot structure, which stems back to the Greeks, on

through Shakespeare and into modern tragedy. In Freytag’s pyramid-based

dramatic model, the climax does not, as one might expect, occur near the end of

a story. Instead this “crisis” typically occurs during the third act of a five-act

play—about midway through a story. Dr. Kip Wheeler of Carson Newman College

calls the moments after the climax the “reversal…[a time] in which the protagonist's

fortunes change irrecoverably for the worse.” And while such a structure

appears less frequently in contemporary fiction, Richard Ford uses the early

reversal and climax as many classicists did; he emphasizes the consequences of

the events he gives away in his first lines. But Ford takes this mode a bit further

and constructs recurring scenes, what I will refer to as

mirrored scenes, in which he shows a scene before the drama, before

Freytag’s pinnacle, and then the same scene again during the reversal, after

the bomb has gone off and the dust has settled at the onset of the falling

action. Ford shows us how quickly (or in some cases how profoundly, after time)

things can change.

The first time I read “Optimists”—that

night when I returned to Boothbay—I flipped ahead upon reaching the page break

after the murder. I remember

wondering where Ford was headed now. These mirrored scenes are an essential

element to the structural success of that story. Before his father comes home, Frank

tells us of a nearly jovial scene. “I was in the kitchen, eating a sandwich…and

my mother was in the living room playing cards with Penny and Boyd Mitchell.

They were drinking vodka and eating the other sandwiches my mother had made.”

But notice how the initial scene is told; it lacks finite images. Ford

leaves the shown details for a later scene, after

the narrator and his mother have bailed the father out of prison:

Inside our house, all the lights were

burning when we got back. It was one o’clock. There were still lights in some

neighbors’ houses. I could see a man at the window across the street, both his

hands to the glass, watching out, watching us…My father stood in the middle of

the living room and looked around, looking at the chairs, at the card table

with cards still on it, at the open doorways to the other rooms. It was as if

he’d forgotten his own house and now saw it again and didn’t like it.

There’s

so much implied, so much subtext when Ford slows down and

shows us the scene. The lights and neighbors, how the family has

become exposed, the cards and card table, how earlier people had been enjoying

this house now laced with violence, the open doors, the father looking around,

how he might’ve taken a different path. Ford patiently skates over the details early,

allowing their meanings and consequences to surface now.

Ford also uses mirrored scenes in

Canada. The night before Dell’s parents

get carted off to jail, Dell and his father work together on a puzzle. “I found

my father alone at the card table with his Niagara Falls puzzle…All the lights

in the front of the house were on. Niagara Falls was almost complete. Only a

few pale pieces of jagged sky needed setting in.” Ford, unlike his

approach in “Optimists,” gives this scene intense detail. He uses Niagara

Falls, of course, to foreshadow the narrator’s looming fate in Canada (another

example of dramatic irony). The lights suggest exposure and an inability to

hide. And Ford presents detail here because, we eventually learn, this is the

last ordinary conversation Dell will have with his soon-to-be-incarcerated father. Then

Dell’s father “suddenly popped the puzzle piece in his mouth, chewed it and swallowed

in a big gulp.” Dell believes his father has performed a magic trick. But

when Dell insists on knowing the piece’s whereabouts, his father claims to have

eaten it, saying, “It’s not a trick

every

time.” Ford suggests that familiar things can and suddenly will

change.

The next morning, Dell’s mother frantically

packs after announcing an unexpected trip to Seattle (an escape plan, of

course). “We have to go now,” she tells Dell. “Put what you’re taking in this.”

She hands him a “pink pillowcase with white scalloped edges.” Dell

gathers his essentials and joins his doomed family in the living room. When

the police finally knock, Dell’s mother drops a dish on the kitchen floor. “It

broke into bits just as my father was pulling the door back to whatever news

was waiting for us.” Ford slowly paints a portrait of this family before its

Freytagian crisis. Ford gives us details we’ll remember.

Ford revisits those details after the

parents get cuffed and stuffed into a police cruiser:

The Niagara Falls puzzle, all put

together, still lay on the card table, lacking only the piece my father had

eaten. It could never be finished and was useless…I stood alone in the middle

of the living room and looked around, my heart beating fast…There was my

pillowcase with my belongings; my mother’s suitcase…I picked up the pieces of

the broken dish my mother had dropped earlier and put them in the trash.

This

scene works similarly to the one from “Optimists.” Dell examines the room, as

if searching for a different path his life could have taken, and he surveys the

immediate wreckage left by his parents’ actions. Ford seems to have mapped his story

out and selected a climax right in the middle of a single scene. The arrest is

sandwiched between these mirrored images because Ford aims to show how quickly

things can turn for the worst. “Those little calibrations are really little,”

Ford recently

told an interviewer. “And their consequences are really big. The

difference between the normal and the aberrance—I've always had an interest in

that…you make one little mistake, you take one star out of the constellation,

and it suddenly no longer is Orion.” Ford shows such a hiccup in

the “calibrations” of this family. A normal morning turns to one littered only with

shards of a life now gone by.

Charles Baxter, in his essay “Against

Epiphanies,” shows hostility toward moments of realization. He’s sick of epiphanies:

“In most anthologies of short stories published since the 1940s, insight

endings or epiphanic endings account for approximately 50 to 85 percent of all

the climactic moments.”

Baxter goes

on to say, “The logic of unveiling has become a dominant mode in Anglo-American

writing, certainly in fiction…We watch as a hidden presence, some secret logic,

rises to visibility and serves as the climactic revelation.” He believes

the epiphanies he reads are unearned.

But Ford’s protagonists do not come to understand

their lives until long after changes take place. Ford doesn’t give his

characters a “hidden presence” or an in-scene insight.

Instead he uses the aforementioned reflective

narrative voice, the temporal space it allows, and the Freytagian story

structure to flash forward and show the consequences of the stories in the present

day, which for “Optimists” is over twenty years to 1982, and for

Canada is nearly fifty years to 2010.

Ford allows for realizations, but not until his stories’ falling actions and

eventual denouements, long after traumatic actions take place.

He wants “

to see that arc of consequence,” wants to see how hardships can be ultimately overcome,

or at least dealt with reasonably in the future.

The final scene from 1959 in “Optimists”

isn’t the last scene of the story, and doesn’t, as one might expect, possess

any epiphanic qualities. Conversely, the narrator, Frank, and his mother

examine their inability to make sense of his father’s actions. His mother tells

about a duck she once saw frozen into the ice, left helpless as its mates flew

away into the wintertime sky. “It’s wildlife,” the mother laments. “Some always

get left back…Maybe that’s just what this is. Just a coincidence.” With

these lines, Ford acknowledges life’s unknowable things, how we can’t

rationally explain much until later. And, as Charles Baxter says, characters needn’t be

“validated by a conclusive insight or a brilliant, visionary stop-time moment.

Stories can arrive somewhere interesting without claiming any wisdom or

clarification…can be a series of clues but not a solution, an unfolding of a

mystery instead of a revelation.” Ford and Baxter both suggest that

it’s okay to lack a lexicon, to be rendered speechless.

At the onset of the story’s denouement,

Ford finally allows Frank, now a man of forty-three, to make a bit of sense from

the events of years before:

The most important things in your life

can change so suddenly, so irrevocably, that you can forget even the most

important of them and their connectedness, you are so taken up by the

chanciness of all that’s happened and by all that could and will happen next. I

now no longer remember the exact year of my father’s birth, or how old he was

when I last saw him…

The

narrator has nearly come to believe what his mother told him twenty years

before. Even now the “epiphany” is vague and doesn’t give finite meaning to the

murder his father committed and its effect on the family. Ford then moves the

story forward, starts disclosing information about the time that’s passed since

1959; he describes the tangible consequences. Frank has, in a sense, erased his

father from memory, and he presents this material as if he’s not surprised by

the outcome, saying, “When you’re young, these things seem unforgettable and at

the heart of everything. But they slide away and are gone when you are not so

young.” All this seems natural to think about years after. The narrator

has had plenty of time to wonder about the year when “life changed for all of us and forever.”

Then Ford brings the story present. “A

month ago I saw my mother,” Frank says. After he mentions he’s been through a

divorce, she replies, “You’ll never get anything fixed just right. That’s your

mother’s word. Your father and I had a marriage…A lot of it was just wrong.”

Even years later, Ford alludes to the mysteries of our actions and

decisions. Nothing will ever get “fixed,” or entirely figured out. But the

scene ends with an oddly hopeful moment. The mother says her son reminds her

of his father, calls their family’s time together before the murder “happy

enough times.” The story closes like this: “And she bent down and

kissed my cheek through the open window and touched my face with both her

hands, held me for a moment that seemed like a long time before she turned

away, finally, and left me there alone.” Hope can be found in a small

moment years after terrible events. If this story has an epiphany, that’s

it. Horrible things are survivable. Frank’s encounter with his mother presents

the realities of their lives—that they’ve lost touch and will probably never

regain closeness, that a mother can still give her son a wise word and have a tender

moment with him years after their family’s collapse.

Canada ends in similar

fashion. After their parents’ incarceration, Dell’s twin sister Berner flees to

California and Dell is taken across the Canadian border and put in the care of

an American, Arthur Remlinger. Dell digs goose-hunting pits and sets decoys for

tourist hunters. But Remlinger is in exile, running from a crime committed in the

US years before. And by the end of his stay in Saskatchewan

, Dell becomes an accomplice in a double-murder, eventually burying

the bodies in the goose pits he earlier helped dig (another example of a

mirrored scene). After the murders, Ford eases Dell into that temporally

reflective voice, which Ford has dipped into throughout the novel. But even then

Dell does not claim to understand the events of his youth—a time now fifty

years behind him. He says, “Can I even speak of the effect of witnessing the Americans’

killing—the effect on me? I’ll have to make the words up, since the true effect

is silence.” “Events must sink into the ground,” he continues, “and

percolate up naturally again for me to pay them proper heed” Ford, it

would seem, agrees with Baxter, who says, “We can have stories of real consequence in

which no discursive insight appears.” Both writers suggest that a truth-bearing

consequence to a reader is more important than an epiphany is to a fictional

character.

Dell goes on to say that since 1960, he

has tried “to mediate among the good counsels… generosity, longevity,

acceptance, relinquishment, letting the world come to me—and, with these

things, to make a life.” In that life Dell comes to reside in Canada, and,

after several years, when he revisits the site where he buried

the murdered men, Dell still can’t mine meaning from all that’s happened. “I

stood [where I helped bury the men], hands in my trouser pockets, toes in the

dust, and tried to make it all signify, be revelatory, as if I needed that. But

I couldn’t.” Ford turns the expectation of an epiphany on its head and

presents a man who

wants the

epiphany, wants to feel overcome with clarifying emotions; yet Dell is at a

loss.

The true consequences of Dell’s

experiences finally surface in

Canada’s

final twenty pages. Berner, whom Dell has seen just a few times since their

separation in 1960, is dying of lymphoma. After hearing the news, Dell muses on

his conduct since his family’s ruinous end. “It made me realize how much I’d

wanted to erase them,” Dell says of his family, “how much my happiness was

pinioned to their being gone.” Now Ford allows Dell a bit of a realization;

it takes place fifty years after the novel’s events. Ford’s novel does not lean

on, as Baxter says, a “hidden presence” or “secret logic.” Instead, it uses the mitigating

effects of the passage of time.

In his final meeting with Berner, Dell

begins to understand that he’ll never really know his sister. As he waits

outside her home, he has a moment with her partner, who “turned and walked in a

stiff, dignified way to the corner of the trailer and was gone…He didn’t want

to meet me. I understood perfectly well. I was late on the scene.” Dell

begins to wrestle with the long-term consequences of his choices—not just on

him but on his sister and the way she views him, at a distance from her failed

life, from a life that took her through “at least three husbands” and several

jobs, including “a waitress in a casino…a waitress in a restaurant…a nurse’s

assistant in a hospice.” Dell wonders if he’s partially to blame—for not

sticking around or tracking her down, for not guiding her toward a successful,

ultimately prosperous life like the one he’s attained as a grown man. Berner is

“bitter about the ‘substitute life’ she’d led instead of the better one she

should’ve led if it had all worked out properly.” And therefore the only

epiphany here, the one that speaks a universal truth, is a simple one: “If you

tolerate loss well,” as Dell says in the final passage of the novel, “manage

not to be a cynic through it all; to subordinate, as Ruskin implied, to keep

proportion, to connect the unequal things into a whole that preserves good”—you can ultimately aspire to an all right life after your world gets

rocked by the poor decisions of others. But if you fail to do those things, as

Berner has, you’ll over-think what could have been. This is the real

consequence of the robberies and murders, and Ford’s reflective voice and

Freytagian story arc allow us to go as far into the future as needed to better

understand the meaning of Dell’s story and, most importantly, his

earned revelation, which he’s only come to

understand over the course of fifty years.

Ford follows similar patterns throughout

his body of work. His 1990 novel

Wildlife

opens like this: “In the Fall of 1960, when I was sixteen and my father was

for a time not working, my mother met a man named Warren Miller and fell in

love with him.” Ford’s novel deals with the violent consequences of

infidelity. During the falling action of his story “Great Falls,”

Ford writes, “Things seldom end in one

event,” thus acknowledging his interest in what happens

after.

Ford goes so far to have a character, in his novella “Jealous,”

another Montana story from his collection

Women with Men, say this: “Of course it’s not what happens, it’s what you do with

what happens.” And even Ford’s

classic Frank Bascombe novels deal with consequence.

The Sportswriter begins with the death of the protagonist’s son and

the end of his marriage.

The Lay of the Land starts with Bascombe recovering from prostate cancer. The list goes on.

In

The Guardian, Ford once called himself “a comer-backer.”

That day I drove back to Boothbay and continued

reading

Rock Springs. That night I

read until I slept. That next morning I drank coffee and read “Communist” and

the collection’s haunting final lines: “My mother and I never talked in that

way again, and I have not heard her voice now in a long, long time.” I was

spellbound but didn’t know why. Now, years later I see, at least initially, the

stories reminded me of the books that turned me into a teenaged reader, a

wannabe writer, stories like

Into the

Wild and

The Perfect Storm, stories

that deal with real-life truths, books that spill the beans up front and deal

with tragic consequences.

I never finished writing the piece on

Boothbay’s lobstermen. But that day in Damariscotta ultimately turned me toward

contemporary fiction. Ford’s work led me to the rest of the “dirty realists,” Raymond

Carver, Tobias Wolff, Ann Beattie and others: writers in a tradition that every

day I work to be a part of. Back then I couldn’t have told you I’d care more

about fiction than most anything else, or that I’d enroll in a graduate creative

writing program and send stories to journals and works-in-progress to writers I

deeply admire. It takes time to find a vocabulary for the events that mean the

most, on and off the page. I’m certainly glad I drove River Road and found a

display of Richard Ford’s fiction laid out like a meal before me.

Andrew Sottile lives, writes and teaches in Oregon. An MFA candidate at Pacific University, he is at work on a collection of stories set on the coast of Maine and a novel.