Today marks the anniversary of Charles Dickens' almost-death (in 1865) and his actual-death (in 1870). For someone like Dickens--whose works teem with coincidence, fate, mistaken identities and sub-plots that merge and bring his novels full circle with a sentimental clash and clatter--the fact that near-death and eventual-death were on the same day five years apart...well, the mind reels at how perfectly it all played out. I'm tempted to believe Dickens wrote his own death scene.

I, too, almost died on this date. Again, the brain spins at the coincidence. I make no secret of the fact that Dickens has been, is, and will always be my inspiration, my lamppost, my touchstone, and my mapmaker in all of my writing. I share with John Irving the deepest respect and reverence for our greatest novelist. To know that we share a Near-Deathday is both weird and delightful.

My story is less like a scene from a Victorian novel than one from a poorly-acted action-comedy. On this day in 1982, I was hiking in Grand Teton National Park with a buddy of mine. We'd set out from Jenny Lake, bound for Inspiration Point, but stopped for a rest beside a glacial stream. I saw what looked like a good photo opportunity and ventured out along the rocks which lined the swift-running water (which, I wrote that night in my diary, looked like "thousands of gallons of spittle"). I had my eye to the viewfinder and didn't see the algae slicking the rock under my tennis shoe. It was straight out of a cartoon where the clumsy oaf hits the banana peel and there's a rising whistle sound on the soundtrack:

whup-whup-whooo! The foot slipped, I cartwheeled, the camera arced through the air, and I plunged into the ice-cube water. My hands dug for a fingerhold on the bank but the current sucked me to the middle of the stream. I went under, I inhaled water, I popped up like a cork, then I was pinballed between three boulders. At one point, The Hand of God conveniently spun me around so I was facing downstream.

Except that there

was no downstream. The water ended abruptly fifteen feet in front of me and I was looking at blank air between me and the crowns of the nearby pine trees, whose trunks were twenty-five feet somewhere below me.

In the space of the next five seconds, here's what went through my brain:

00:00:01 What the fuh--?

00:00:01.5 Ohmygod it's a waterfall, I'm on the lip of a waterfall!

00:00:02.3 I'm going to die

00:00:02.6 Aaaiiiiiiiiiiieeeeeeeeeee!

00:00:03 Gosh, I always loved Mom's homemade chocolate-chip cookies and now I'll never get to taste them again, and what about marriage and kids, and, dammit, I'll never know whether or not George Lucas will ever finish the Star Wars trifecta of trilogies like he promised....

00:00:04.5 This is it, this is it, this is THE END

00:00:04.7 My life flashed, etc.

00:00:05 Why oh why did I never read all of Charles Dickens' novels like I said I would?

There came a watery swoosh, the silence of falling, then a roaring splashdown in a pool at the foot of the waterfall.

I was okay. Drenched, gagging water, and a little ashamed of the girly-scream I'd unleashed up there before The Plunge, but otherwise okay. I stood there in the shallow water for several minutes, shaking and wondering what kind of life I'd lead from here on out, now that I'd been killed and resurrected in the blink of an eye.

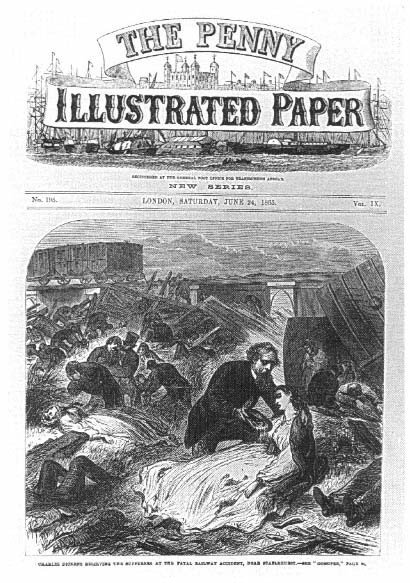

On this same date back in 1865, Charles Dickens got just as close to the Great Beyond. Dickens, then 53 years old, was traveling by train while returning from a trip to Paris when he was involved in what became known as the Staplehurst Railway Disaster. Riding in the first-class carriage with the novelist were his mistress Ellen Ternan and her mother. In his coat pocket, Dickens carried the latest handwritten pages of

Our Mutual Friend

, his novel-in-progress. Here is how Edgar Johnson described the incident in

his biography of Dickens

:

At eleven minutes past three the train entered on a straight stretch of track between Headcorn and Staplehurst. One third of the way there came a slight dip in the level country to a stream bed crossed by a railway bridge of girders. Suddenly the driver clamped on the brakes, reversed his engine, and whistled for the guards to apply their hand brakes. He had seen a flagman with a red flag and a gap of ripped-up rails.

A crew of repairmen were carrying on a routine replacement of worn timbers, but their foreman had looked at the time-table for the next day and imagined the train would not be along for another two hours. The flagman was supposed to be 1,000 yards beyond the gap and to have laid down fog signals, but that day he had neglected the signals and was only 550 yards from the bridge. When the engineer saw him it was too late. As he reached the bridge the train was still going almost thirty miles an hour.

The engine leaped the 42-foot gap in the rails and ran to the farther bank of the river bed. The guard's van that followed was flung to the parallel track, dragging the next coach with it. The coach immediately behind was that in which Dickens and Ellen were seated. It jolted partly over the side of the bridge, ten feet above the stream, with its rear end on the field below. The other coaches ran down the bank, turning upside down in the marshy ground, where four of them were smashed to matchwood.

Dickens climbed out of his dangling railcar through a window, and found a worker to give him a key so he could free Ellen and her mother from the tilting carriage. He went back for his brandy flask, filled his hat with water and started walking through the wreckage and the carnage, giving first aid wherever he could. Johnson continues:

The screams of the sufferers were appalling. A staggering man covered with blood had "such a frightful cut across the skull," Dickens said, "that I couldn't bear to look at him. I poured some water over his face, gave him some drink, then gave him some brandy, and laid him down in the grass...." One lady who had been crushed to death was laid on the bank just as her husband, screaming, "My wife! my wife!" rushed up and found her a mangled corpse. Dickens was everywhere, helping everyone. When he had done everything he could, he remembered that he had the manuscript of the next number of Our Mutual Friend with him, and coolly climbed into the carriage to retrieve it.

In the Postscript to

Our Mutual Friend, Dickens wrote with characteristic wit about how he returned to save his characters:

On Friday the Ninth of June in the present year, Mr and Mrs Boffin (in their manuscript dress of receiving Mr and Mrs Lammle at breakfast) were on the South Eastern Railway with me, in a terribly destructive accident. When I had done what I could to help others, I climbed back into my carriage— turned over a viaduct, and caught aslant upon the turn—to extricate the worthy couple. They were much soiled, but otherwise unhurt. The same happy result attended Miss Bella Wilfer on her wedding day, and Mr Riderhood inspecting Bradley Headstone's red neckerchief as he lay asleep. I remember with devout thankfulness that I can never be much nearer parting company with my readers for ever, than I was then, until there shall be written against my life, the two words with which I have this day closed this book:—THE END

THE END would come sooner than he imagined (and much, much sooner than we, his legion of fans, would have wanted).

Our Mutual Friend was the last novel Dickens would ever complete--and, in my opinion, it remains one of his best, if not

the best (I also have a fondness for the less-popular

Dombey and Son

).

Dickens never got over Staplehurst. In

his biography

, Peter Ackroyd writes, "travelling became for him the single most distressing activity." Dickens' daughter Mary recalled, "My father's nerves never really were the same again...we have often seen him, when travelling home from London, suddenly fall into a paroxysm of fear, tremble all over, clutch the arms of the railway carriage, large beads of perspiration standing on his face, and suffer agonies of terror. We never spoke to him, but would touch his hand gently now and then. He had, however apparently no idea of our presence; he saw nothing for a time but that most awful scene."

(Speaking of "most awful," if you want an alternate version of the Staplehurst accident and its residual effect on Dickens, you can slog through Dan Simmons' novel

Drood

. I don't recommend it, but masochistic readers can get their 770-page fill of how Dickens and Wilkie Collins descend to the sewers under London pursuing, and pursued by, a monster called Drood who first appears to Dickens out of the Staplehurst wreckage in the novel's opening pages.)

Dickens ducked the Grim Reaper's scythe at Staplehurst, but he wasn't so quick on his feet five years later. On June 8, 1870, he awoke early "in excellent spirits," Ackroyd tells us. After breakfast, he went to the writing desk in his custom-built Swiss chalet and worked on

The Mystery of Edwin Drood

for several hours. He ate lunch, smoked a cigar, then returned to

Drood, penning a final passage which opens with "A brilliant morning shines on the old city"--which, Ackroyd reminds us, "echoes the very first sentence of his first novel,

The Pickwick Papers

: 'The first ray of light which illumines the gloom...'"

Like I said, it's as if Dickens was neatly writing his death scene, one eye on the sentimental movies which were half a century in the future.

He returned to the house for dinner, appearing "tired, silent and abstracted." As he sat down to the meal, his sister-in-law Georgina "noticed a change both in his colour and his expression," Ackroyd writes.

She asked him if he were ill, and he replied, "Yes, very ill; I have been very ill for the last hour." She wanted to send immediately for a doctor but he forbade her to do so, saying that he wanted to go to London that evening after dinner. But then something happened. He experienced some kind of fit against which he tried to struggle--he paused for a moment and then began to talk very quickly and indistinctly, at some point mentioning (his close friend and biographer) Forster. She rose from her chair, alarmed, and told him to "come and lie down."

"Yes," he said "On the ground."

But as she helped him he slid from her arms and fell heavily to the floor.

Dickens never regained consciousness. Doctors arrived, but could do nothing for him; the stroke had done its work. Telegrams were sent and family members rushed to the Gad's Hill home, standing helpless at his side, weeping as he slipped away from them. He lingered in that suspended state for nearly a day. Then, Ackroyd concludes in his biography:

At five minutes before six o'clock in the evening his breathing suddenly diminished and he began to sob. Fifteen minutes later he heaved a deep sigh, a tear rose to his right eye and trickled down his cheek. He was dead. Charles Dickens had left the world.

One-hundred-and-twelve years later, I would find myself teetering on the edge of a waterfall, certain I was about to plunge to my doom. Instead of making a last-minute bargain with God, I made a personal vow to read the complete works of Charles Dickens.

To this day, I have read every novel, every short story, his early journalism and the account of his visit to America. The only books on my Dickens shelf which remain unread are

Holiday Romance and Other Writings for Children

,

Pictures From Italy

and

The Uncommercial Traveller

.

I only hope I live long enough to read them.