Postcards. As I stumble, fumble, tumble, bumble, mumble my way through

Lolita, and reach the first two chapters of Part Two, my head fills with postcards. As those of you who have read Vladimir Nabokov's 1955 novel may recall, these are the chapters where Humbert Humbert and Lolita spend a year ("1947-1948, August to August") criss-crossing the United States, trying to stay one step ahead of the law and its Mann Act (though I don't think H. H. sees it quite that way).

|

| Cover design by Peter Mendelsund |

For those of you who

haven't read

Lolita (if not, why not? [pot calling the kettle names here because, until September of last year, I, too, was a

Lolita virgin]) and who want to remain blithely spoiler-free: feel free to skip over the next paragraph and just dive headlong into the novel excerpts.

Astute readers will also remember this jalopy jaunt across America marks the sexual blossoming of the Humbert-Lolita relationship now that Charlotte, Lolita's mother, is out of the picture (and growing hazier by the minute). There is much I could say in this space about the sex, and even more I could say about Nabokov's delicious, delirious punnage, but what I'm most interested in today is the way he captures post-war America. And so, on this Memorial Day weekend, when many of you are probably preparing to drive, fly, paddle, and pogo-stick out on your own (presumably shorter) vacations, I thought it would be interesting to capture the Hum-Lo trip visually. I've inserted photos and postcards to show the places (actual, and merely imagined on my part) the lovers visited on their odyssey. It was, Humbert later tells us, an "extravagant year....lodgings and food cost us around 5,500 dollars; gas, oil and repairs, 1,234, and various extras almost as much; so that during about 150 days of actual motion (we covered about 27,000 miles!) plus some 200 days of interpolated standstills, this modest

rentier spent around 8,000 dollars, or better say 10,000 because, unpractical as I am, I have surely forgotten a number of items." But there is much he remembers. Ladies and gentlemen of the jury, I present you with Exhibits A & B, the last paragraph of Chapter 1 and the beginning of Chapter 2. Buckle up and enjoy the ride.

My lawyer has suggested I give a clear, frank account of the itinerary we followed, and I suppose I have reached here a point where I cannot avoid that chore. Roughly, during that mad year (August 1947 to August 1948), our route began with a series of wiggles and whorls in New England, then meandered south, up and down, east and west; dipped deep into

ce qu’on appelle Dixieland, avoided Florida because the Farlows were there, veered west, zigzagged through corn belts and cotton belts (this is not

too clear I am afraid, Clarence , but I did not keep any notes, and have at my disposal only an atrociously crippled tour book in three volumes, almost a symbol of my torn and tattered past, in which to check these recollections); crossed and recrossed the Rockies, straggled through southern deserts where we wintered; reached the Pacific, turned north through the pale lilac fluff of flowering shrubs along forest roads; almost reached the Canadian border; and proceeded east, across good lands and bad lands, back to agriculture on a grand scale, avoiding, despite little Lo’s strident remonstrations, little Lo’s birthplace, in a corn, coal and hog producing area; and finally returned to the fold of the East, petering out in the college town of Beardsley.

* * *

Now, in perusing what follows, the reader should bear in mind not only the general circuit as adumbrated above, with its many sidetrips and tourist traps, secondary circles and skittish deviations, but also the fact that far from being an indolent

partie de plaisir, our tour was a hard, twisted, teleological growth, whose sole

raison d’ětre (these French clichés are symptomatic) was to keep my companion in passable humor from kiss to kiss. Thumbing through that battered tour book, I dimly evoke that Magnolia Garden in a southern state which cost me four bucks and which, according to the ad in the book, you must visit for three reasons: because John Galsworthy (a stone-dead writer of sorts) acclaimed it as the world’s fairest garden; because in 1900 Baedeker’s Guide had marked it with a star; and finally, because…O, Reader, My Reader, guess!…because children (and by Jingo was not my Lolita a child!) will “walk starry-eyed and reverently through this foretaste of Heaven, drinking in beauty that can influence a life.” “Not mine,” said grim Lo, and settled down on a bench with the fillings of two Sunday papers in her lovely lap.

We passed and re-passed through the whole gamut of American roadside restaurants, from the lowly Eat with its deer head (dark trace of long tear at inner canthus),

“humorous” picture post cards of the posterior “Kurort” type,

impaled guest checks, life savers, sunglasses, adman visions of celestial sundaes, one half of a chocolate cake under glass, and several horribly experienced flies zigzagging over the sticky sugar-pour on the ignoble counter;

and all the way to the expensive place with the subdued lights, preposterously poor table linen, inept waiters (ex-convicts or college boys), the roan back of a screen actress, the sable eyebrows of her male of the moment, and an orchestra of zoot-suiters with trumpets. We inspected the world’s largest stalagmite in a cave where three southeastern states have a family reunion; admission by age; adults one dollar, pubescents sixty cents.

A granite obelisk commemorating the Battle of Blue Licks, with old bones and Indian pottery in the museum nearby, Lo a dime, very reasonable.

The present log cabin boldly simulating the past log cabin where Lincoln was born.

A boulder, with a plaque, in memory of the author of “Trees” (by now we are in Poplar Cove, N.C., reached by what my kind, tolerant, usually so restrained tour book angrily calls “a very narrow road, poorly maintained,” to which, though no Kilmerite, I subscribe).

From a hired motor-boat operated by an elderly, but still repulsively handsome White Russian, a baron they said (Lo’s palms were damp, the little fool), who had known in California good old Maximovich and Valeria, we could distinguish the inaccessible “millionaires’ colony” on an island, somewhere off the Georgia coast.

We inspected further: a collection of European hotel picture post cards in a museum devoted to hobbies at a Mississippi resort, where with a hot wave of pride I discovered a colored photo of my father’s Mirana, its striped awnings, its flag flying above the retouched palm trees. “So what?” said Lo, squinting at the bronzed owner of an expensive car who had followed us into the Hobby House. Relics of the cotton era.

A forest in Arkansas and, on her brown shoulder, a raised purple-pink swelling (the work of some gnat) which I eased of its beautiful transparent poison between my long thumbnails and then sucked till I was gorged on her spicy blood.

Bourbon Street (in a town named New Orleans) whose sidewalks, said the tour book, “may [I liked the “may”] feature entertainment by pickaninnies who will [I liked the “will” even better] tap-dance for pennies” (what fun), while “its numerous small and intimate night clubs are thronged with visitors” (naughty).

Collections of frontier lore.

Ante-bellum homes with iron-trellis balconies and hand-worked stairs, the kind down which movie ladies with sun-kissed shoulders run in rich Technicolor, holding up the fronts of their flounced skirts with both little hands in that special way, and the devoted Negress shaking her head on the upper landing.

The Menninger Foundation, a psychiatric clinic, just for the heck of it.

A patch of beautifully eroded clay; and yucca blossoms , so pure, so waxy, but lousy with creeping white flies.

Independence, Missouri, the starting point of the Old Oregon Trail;

and Abilene, Kansas, the home of the Wild Bill Something Rodeo.

Distant mountains. Near mountains. More mountains; bluish beauties never attainable, or ever turning into inhabited hill after hill;

south-eastern ranges, altitudinal failures as alps go; heart and sky-piercing snow-veined gray colossi of stone, relentless peaks appearing from nowhere at a turn of the highway;

timbered enormities, with a system of neatly overlapping dark firs, interrupted in places by pale puffs of aspen; pink and lilac formations, Pharaonic, phallic, “too prehistoric for words” (blasé Lo);

buttes of black lava; early spring mountains with youngelephant lanugo along their spines; end-of-the-summer mountains, all hunched up, their heavy Egyptian limbs folded under folds of tawny moth-eaten plush; oatmeal hills, flecked with green round oaks; a last rufous mountain with a rich rug of lucerne at its foot.

Moreover, we inspected: Little Iceberg Lake, somewhere in Colorado, and the snow banks, and the cushionets of tiny alpine flowers, and more snow; down which Lo in red-peaked cap tried to slide, and squealed, and was snowballed by some youngsters, and retaliated in kind

comme on dit. Skeletons of burned aspens, patches of spired blue flowers. The various items of a scenic drive.

Hundreds of scenic drives, thousands of Bear Creeks,

Soda Springs,

Painted Canyons.

Texas, a drought-struck plain. Crystal Chamber in the longest cave in the world, children under 12 free, Lo a young captive. A collection of a local lady’s homemade sculptures, closed on a miserable Monday morning, dust, wind, witherland. Conception Park, in a town on the Mexican border which I dared not cross. There and elsewhere, hundreds of gray hummingbirds in the dusk, probing the throats of dim flowers. Shakespeare, a ghost town in New Mexico, where bad man Russian Bill was colorfully hanged seventy years ago.

Fish hatcheries.

Cliff dwellings.

The mummy of a child (Florentine Bea’s Indian contemporary). Our twentieth Hell’s Canyon.

Our fiftieth Gateway to something or other

fide that tour book, the cover of which had been lost by that time.

A tick in my groin. Always the same three old men, in hats and suspenders, idling away the summer afternoon under the trees near the public fountain. A hazy blue view beyond railings on a mountain pass, and the backs of a family enjoying it (with Lo, in a hot, happy, wild, intense, hopeful, hopeless whisper—“Look, the McCrystals, please, let’s talk to them, please”— let’s talk to them, reader!—“ please! I’ll do anything you want, oh, please …”). Indian ceremonial dances, strictly commercial.

ART: American Refrigerator Transit Company.

Obvious Arizona,

pueblo dwellings,

aboriginal pictographs, a dinosaur track in a desert canyon, printed there thirty million years ago, when I was a child.

A lanky, six-foot, pale boy with an active Adam’s apple, ogling Lo and her orange-brown bare midriff, which I kissed five minutes later, Jack. Winter in the desert, spring in the foothills, almonds in bloom. Reno, a dreary town in Nevada, with a nightlife said to be “cosmopolitan and mature.”

A winery in California, with a church built in the shape of a wine barrel.

Death Valley. Scotty’s Castle.

Works of Art collected by one Rogers over a period of years. The ugly villas of handsome actresses. R. L. Stevenson’s footprint on an extinct volcano.

Mission Dolores: good title for book.

Surf-carved sandstone festoons. A man having a lavish epileptic fit on the ground in Russian Gulch State Park.

Blue, blue Crater Lake.

A fish hatchery in Idaho

and the State Penitentiary.

Somber Yellowstone Park

and its colored hot springs,

baby geysers,

rainbows of bubbling mud—symbols of my passion.

A herd of antelopes in a wildlife refuge.

Our hundredth cavern, adults one dollar, Lolita fifty cents.

A chateau built by a French marquess in N.D.

The Corn Palace in S.D.;

and the huge heads of presidents carved in towering granite.

The Bearded Woman read our jingle and now she is no longer single.

A zoo in Indiana where a large troop of monkeys lived on concrete replica of Christopher Columbus’ flagship.

Billions of dead, or halfdead, fish-smelling May flies in every window of every eating place all along a dreary sandy shore.

Fat gulls on big stones as seen from the ferry

City of Sheboygan, whose brown woolly smoke arched and dipped over the green shadow it cast on the aquamarine lake.

A motel whose ventilator pipe passed under the city sewer. Lincoln’s home, largely spurious, with parlor books and period furniture that most visitors reverently accepted as personal belongings.

We had rows, minor and major. The biggest ones we had took place: at Lace work Cabins, Virginia;

on Park Avenue, Little Rock, near a school;

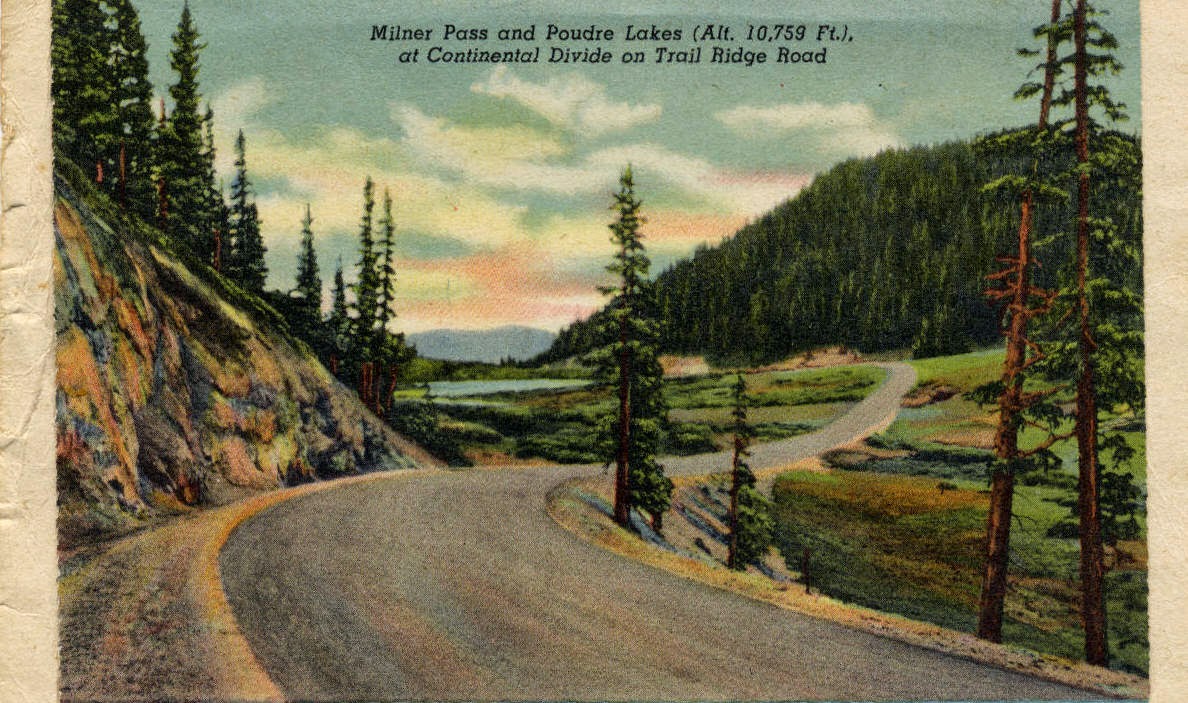

on Milner Pass, 10,759 feet high, in Colorado;

at the corner of Seventh Street and Central Avenue in Phoenix, Arizona;

on Third Street, Los Angeles, because the tickets to some studio or other were sold out;

at a motel called Poplar Shade in Utah, where six pubescent trees were scarcely taller than my Lolita, and where she asked,

à propos de rien, how long did I think we were going to live in stuffy cabins, doing filthy things together and never behaving like ordinary people? On N. Broadway, Burns, Oregon, corner of W. Washington, facing Safeway, a grocery.

In some little town in the Sun Valley of Idaho, before a brick hotel, pale and flushed bricks nicely mixed, with, opposite, a poplar playing its liquid shadows all over the local Honor Roll.

In a sage brush wilderness, between Pinedale and Farson.

Somewhere in Nebraska, on Main Street, near the First National Bank, established 1889, with a view of a railway crossing in the vista of the street, and beyond that the white organ pipes of a multiple silo.

And on McEwen St., corner of Wheaton Ave., in a Michigan town bearing his first name.

+(1).jpg)

.jpeg)