The Last Werewolf

Three months into 2011, and I may have already found my favorite book of the year.I love it when bloggers get all frothy around the mouth.

Due out this summer, Glen Duncan’s The Last Werewolf is being cast by some as “genre fiction for non-genre-fiction readers,” the same way as Cronin’s The Passage was in 2010. To be honest, that kind of terminology makes me cringe. To me, saying a novel transcends genre always sounds like an insult to genre fiction, literary fiction, and the book.

So, I’ll just say that The Last Werewolf is a fucking awesome book. It’s surprising, it’s beautiful, and it sets the bar high for every other book I read this year.

We the Animals

We wanted more. We knocked the butt ends of our forks against the table, tapped our spoons against our empty bowls; we were hungry. We wanted more volume, more riots. We turned up the knob on the TV until our ears ached with the shouts of angry men. We wanted more music on the radio; we wanted beats, we wanted rock. We wanted muscles on our skinny arms. We had bird bones, hollow and light, and we wanted more density, more weight. We were six snatching hands, six stomping feet; we were brothers, boys, three little kings locked in a feud for more.Months before its publication date, We the Animals already has the jet-propulsion of an endorsement from Michael Cunningham (The Hours

Jamrach's Menagerie

I was born twice. First in a wooden room that jutted out over the black water of the Thames, and then again eight years later in the Highway, when the tiger took me in his mouth and everything truly began.Honestly, do you really expect me to stop there? Must. Keep. Reading. Jamrach's Menagerie is due out this month and it already has my full, undivided attention.

The Map of Time

Andrew Harrington would have gladly died several times over if that meant not having to choose just one pistol from among his father's vast collection in the living room cabinet. Decisions had never been Andrew's strong point. On close examination, his life had been a series of mistaken choices, the last of them threatening to cast its lengthy shadow over the future. But that life of unedifying blunders was about to end. This time he was sure he had made the right decision, because he had decided not to decide. There would be no more mistakes in the future because there would be no more future. He was going to destroy it completely by putting one of those guns to his right temple. He could see no other solution: obliterating the future was the only way for him to eradicate the past.Here's the Jacket Copy: "Set in Victorian London with characters real and imagined, The Map of Time is a page-turner that boasts a triple play of intertwined plots in which a skeptical H. G. Wells is called upon to investigate purported incidents of time travel and to save lives and literary classics, including Dracula and The Time Machine, from being wiped from existence. What happens if we change history? Félix J. Palma explores this question in The Map of Time, weaving a historical fantasy as imaginative as it is exciting—a story full of love and adventure that transports readers to a haunting setting in Victorian London for their own taste of time travel." It sounds like a mishmash of Jasper Fforde's Thursday Next

In Caddis Wood

Carl sits upright in bed and gazes into the furry dark. Something hot and galloping in the room, black walls leaping like a Tilt-A-Whirl, the steady thump of his heart. Terror. Not from a dream, either. Hallie sighs and turns into his arm. There is a stirring in the corner behind the glass door, and he remembers a similar movement that afternoon while he was weeding in the garden. A motion as of a bird startled, jarred into flight. Scanning the shadowy contours of the room, he sees the pale curtain, the silhouette of clothing hung on hooks. He concentrates on each breath, his eyes locked on the steepled pines that frame the edge of the porch, then pads across the wooden floor.

The air outside is resinous, soft, completely still. Only the silver stream moves. Maybe it's the unnatural quiet that has awakened him, the absence of nighttime's customary clamor: leaves, the soughing wind, whine of insects. The moon is sickle shaped and bright, not a single cloud. Everything--trees, sky, birds--is watching.

The Leftovers

Lamb

About the tops of upturned trash bins, black flies scripted the air.I like the construction of the sentence, the specificity of the flies' blackness, and especially that verb "scripted." I don't know how the rest of the book holds up, but Nadzam sure has my attention at this point; she's a writer to watch. Here's the Jacket Copy: "Lamb traces the self-discovery of David Lamb, a narcissistic middle aged man with a tendency toward dishonesty, in the weeks following the disintegration of his marriage and the death of his father. Hoping to regain some faith in his own goodness, he turns his attention to Tommie, an awkward and unpopular eleven-year-old girl. Lamb is convinced that he can help her avoid a destiny of apathy and emptiness, and even comes to believe that his devotion to Tommie is in her best interest. But when Lamb decides to abduct a willing Tommie for a road trip from Chicago to the Rockies, planning to initiate her into the beauty of the mountain wilderness, they are both shaken in ways neither of them expects." Blurb-worthiness: "Lamb is a wonder of a novel. Bonnie Nadzam has offered an exploration of interpersonal and sexual manipulation and power that left me reeling. This is a novel about responsibility, complicity, blame, neglect, and finally love." (Percival Everett, I Am Not Sidney Poitier

Cabin: Two Brothers, a Dream, and Five Acres in Maine

The idea had taken hold of me that I needed nothing so much as a cabin in the woods--four rough walls, a metal roof that would ping under the spring rain, and a porch that looked down a wooded hillside.

I had been city-bound for nearly a decade, dealing with the usual knockdowns and disappointments of middle age. I had lost a job, my mother had died and I was climbing back from a divorce that had left me nearly broke. I was a little wobbly but still standing, and I was looking for something that would put me back in life's good graces. I wanted a project that would engage the better part of me, and the notion of building a cabin--a boy's dream, really--seemed a way to get a purchase on life's next turn. I won't lie. I needed it badly.

Alice Bliss

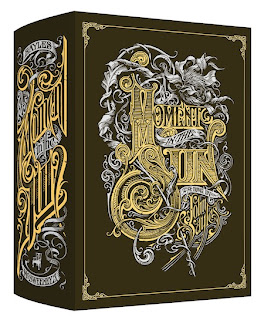

A Moment in the Sun

Johnny Appleseed

Near sunset, one day in mid-March 1845, a seventy-year-old man named John Chapman appeared at the door of a cabin along the banks of the St. Joseph River, a few miles north of Fort Wayne, Indiana. Barefoot, dressed in coarse pantaloons and a coffee sack with holes cut out for his head and arms, Chapman had walked fifteen miles that day through mixed snow and rain to repair a bramble fence that protected one of his orchards. Now, he sought a roof over his head at the home of William Worth and his family—a request readily granted. Chapman had stayed with the Worths before on those few occasions when he felt a need to be out of the weather, a little more than five weeks in all over the previous five-plus years.

Inside, as was his custom, Chapman refused a place at table, taking a bowl of bread and milk by the hearth—or maybe on the chill of the front stoop, staring at the sunset. Accounts vary. The weather might have cleared. Afterward, also a custom, he regaled his hosts with news "right fresh from heaven" in a voice that, one frontier diarist wrote, "rose denunciatory and thrilling, strong and loud as the roar of wind and waves, then soft and soothing as the balmy airs that quivered the morning-glory leaves about his gray beard."

One version of events has him reciting the Beatitudes, from the Gospel According to St. Matthew: "Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven. Blessed are they who mourn, for they shall be comforted. Blessed are the meek, for they shall inherit the earth. …" That could be, but for last words—and this was to be his final lucid night on earth—the Beatitudes are almost too perfect, like those morning-glory leaves fluttering in the old gray beard. More likely, Chapman expounded for the gathered Worth family on the "spiritual truths" of the Bible, its hidden codex, a subject for him of inexhaustible fascination.

John Chapman slept on the hearth, by the fire, that night. On that everyone agrees. By morning, a fever had "settled on his lungs," according to one person present, and rendered him incapable of speech. Within days, perhaps hours, he was dead, a victim of "winter plague," a catch-all diagnosis that dated back to the Middle Ages and included everything from pneumonia and influenza to the cold-weather rampages of the Black Death. Whatever carried him away, Chapman almost certainly did not suffer. The physician who pronounced him dying later said that he had never seen a man so placid in his final passage. Years afterward, Worth family members would describe the corpse as almost glowing with serenity.

That's overblown, of course, but with John Chapman—or Johnny Appleseed, as he eventually became known throughout the Old Northwest—just about everything is.

The Upright Piano Player

Henry Cage seems to have it all: a successful career, money, a beautiful home, and a reputation for being a just and principled man. But public virtues can conceal private failings, and as Henry faces retirement, his well-ordered life begins to unravel. His ex-wife is ill, his relationship with his son is strained to the point of estrangement, and on the eve of the new millennium he is the victim of a random violent act which soon escalates into a prolonged harassment.

As his ex-wife's illness becomes grave, it is apparent that there is little time to redress the mistakes of the past. But the man stalking Henry remains at large. Who is doing this? And why? David Abbott brilliantly pulls this thread of tension ever tighter until the surprising and emotionally impactful conclusion. The Upright Piano Player is a wise and acutely observed novel about the myriad ways in which life tests us—no matter how carefully we have constructed our own little fortresses.

Lost in Shangri-La

On May 13, 1945, twenty-four American servicemen and WACs boarded a transport plane for a sightseeing trip over “Shangri-La,” a beautiful and mysterious valley deep within the jungle-covered mountains of Dutch New Guinea. Unlike the peaceful Tibetan monks of James Hilton’s bestselling novel Lost Horizon, this Shangri-La was home to spear-carrying tribesmen, warriors rumored to be cannibals.

But the pleasure tour became an unforgettable battle for survival when the plane crashed. Miraculously, three passengers pulled through. Margaret Hastings, barefoot and burned, had no choice but to wear her dead best friend’s shoes. John McCollom, grieving the death of his twin brother also aboard the plane, masked his grief with stoicism. Kenneth Decker, too, was severely burned and suffered a gaping head wound.

Emotionally devastated, badly injured, and vulnerable to the hidden dangers of the jungle, the trio faced certain death unless they left the crash site. Caught between man-eating headhunters and enemy Japanese, the wounded passengers endured a harrowing hike down the mountainside—a journey into the unknown that would lead them straight into a primitive tribe of superstitious natives who had never before seen a white man—or woman.

Drawn from interviews, declassified U.S. Army documents, personal photos and mementos, a survivor’s diary, a rescuer’s journal, and original film footage, Lost in Shangri-La recounts this incredible true-life adventure for the first time. Mitchell Zuckoff reveals how the determined trio—dehydrated, sick, and in pain—traversed the dense jungle to find help; how a brave band of paratroopers risked their own lives to save the survivors; and how a cowboy colonel attempted a previously untested rescue mission to get them out.

By trekking into the New Guinea jungle, visiting remote villages, and rediscovering the crash site, Zuckoff also captures the contemporary natives’ remembrances of the long-ago day when strange creatures fell from the sky. A riveting work of narrative nonfiction that vividly brings to life an odyssey at times terrifying, enlightening, and comic, Lost in Shangri-La is a thrill ride from beginning to end.

Sigh. Between The Last Werewolf, Shangri-La, A Moment in the Sun, The Upright Piano Player, and a dozen other new releases, it looks like my summer is already booked.

*TIME magazine

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.