I'd hoped to be writing this morning about Ben Fountain, National Book Award winner. But alas, Billy Lynn's Long Halftime Walk didn't win in last night's ceremony. That honor went to Louise Erdrich's The Round House--which, from what I've heard, deserves the medal. I'd also been pulling for Kevin Powers' powerful Iraq War novel The Yellow Birds, but had actually thought Junot Diaz would take home the prize for This Is How You Lose Her. So, The Round House was the darkest of horses in my National Book Award race.

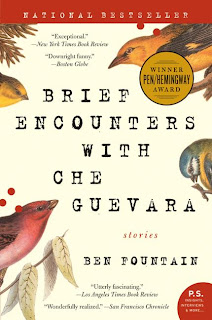

This is not a post meant to detract from Ms. Erdrich's win--I'm happy for her, I truly am. Instead, it's a pulpit for me to tell you how much I enjoyed both of Fountain's books--Brief Encounters with Che Guevara and Billy Lynn's Long Half-Time Walk (the NBA contender). I'd already planned to post this review, regardless of the ceremony's outcome.

Billy Lynn's Long Halftime Walk is like a poison-tipped knife stabbed into the belly of America. It is a scathing, effective criticism of how the nation flounders in a time of war. Well-meaning as some of the eye-bulging, neck-vein-popping post-9/11 patriotism may have been, Fountain sees it as misplaced and misguided. If you're one of those who say "Cut me--I bleed red, white and blue" or who reverently kneel at the Altar of George Dubya or who still believe there are weapons of mass destruction somewhere out there in the Iraqi sands, then you'd best steer away from this novel.

If, on the other hand, you find yourself saying (as Fountain did before he wrote the book), "What has America come to?" then step inside these pages for a closer look at our flawed, complicated country.

Billy Lynn's Long Halftime Walk follows one group of soldiers over the course of one day as they prepare to be feted at half-time during a Thanksgiving Day football game in Texas Stadium (home of "America's team," the Dallas Cowboys). The men of Bravo Squad, newly-famous thanks to footage of an intense firefight in Iraq broadcast by an embedded Fox News crew, will be joined at the center of the field by a pelvis-grinding Destiny's Child, phalanxes of Dallas Cowboy cheerleaders, and a sky full of fireworks. The T-Day game is the culmination of a PR-slick Victory Tour ("One nation, two weeks, eight American heroes") and reminded me of the 2006 movie Flags of Our Fathers, directed by Clint Eastwood, in which a band of survivors from Iwo Jima were paraded across America in the midst of World War Two.

For the soldiers of Bravo Squad, the football game appearance is bittersweet for, as Fountain writes, "in two days they will redeploy for Iraq and the remaining eleven months of their extended tour." But that's 48 hours down the road. "For now they are deep within the sheltering womb of all things American—football, Thanksgiving, television, about eight different kinds of police and security personnel, plus three hundred million well-wishing fellow citizens. Or, as one trembly old guy in Cleveland put it, 'Yew ARE America.'"

The novel follows the titular Specialist Billy Lynn and his comrades as they arrive at the stadium, meet the Cowboys team players, are served drinks in the owner's sky box, pose for photos, and negotiate a movie deal with a has-been Hollywood producer named Albert (my imagination casts Albert Brooks in the role). Fountain stuffs a lot of action into the plot's timespan, from the time the soldiers enter the stadium to the moment they depart in a limousine. Some of the day's events strain credibility, but throughout the book, Fountain makes up for any plot potholes by writing with words that fly like precision-guided missiles. Here, for instance, is how Specialist Lynn feels about being used as a pawn in the publicity tour:

Billy rises and assumes the stance for such occasions, back straight, weight balanced center-mass, a reserved yet courteous expression on his youthful face. He came to the style more or less by instinct, this tense, stoic vein of male Americanism defined by multiple generations of movie and TV actors, which conveniently furnishes him a way of being without having to think about it too much. You say a few words, you smile occasionally. You let your eyes seem a little tired. You are unfailingly modest and gentle with women, firm of handshake and eye contact with men. Billy knows he looks good doing this. He must, because people totally eat it up, in fact they go a little out of their heads. They do! They mash in close, push and shove, grab at his arms and talk too loud, and sometimes they break wind, so propulsive is their stress.

And later, Fountain writes: "People gather. The air turns moist with desire. They want words. They want contact. They want pictures and autographs. Americans are incredibly polite as long as they get what they want."

Speaking as someone who went to war and came back to that same chorus of "Thank you for your service" greetings at the airport and in coffee shops, bookstores and sidewalks across America, I can tell you that Fountain perfectly captured the earnest-but-ignorant attitude of those who never served. It's not their fault--America drinks from the teat of the media in small, 90-second sips--but, as I'm sure any veteran will tell you, the thankyouforyourservice has become something of a rubber mallet striking a knee. Thank you for thanking me, but what do you really mean? For some Americans, the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan are little more than political puzzles to be snapped together with bloodless practicality. As Fountain notes, "the war is a problem to be solved with correct thinking and proper resource allocation." Tell that to those who, as Fountain writes, have "dealt much death and received much death and smelled it and held it and slopped through it in their boots, had it spattered on their clothes and tasted it in their mouths." Nowhere is that military-civilian disconnect more apparent than it is in the flashback scene to the homecoming Billy endures at his parents' house a few days before the Thanksgiving game:

A few of the neighbors got word of Billy’s visit and dropped by with cakes and casseroles, as if there’d been a death in the family. Mr. and Mrs. Wiggins from church. Opal George from across the street. The Kruegers. We are so proud. We always knew. So brave, so blessed, so honored. Edwin! I yelled, come quick! Billy Lynn’s on TV and he’s taking out a whole mess of al-Qaedas! Nice people but they did go on, and so fierce about the war! They were transformed at such moments, talking about war—their eyes bugged out, their necks bulged, their voices grew husky with bloodlust. Billy wondered about them then, the piratical appetites in these good Christian folk, or maybe this was just their way of being polite, of showing how much they appreciated him.

Soon after finishing Billy Lynn's Long Halftime Walk, I turned to Fountain's first book, the 2007 collection of short stories Brief Encounters with Che Guevara. I was not surprised to find the same kind of finely-honed language which Fountain uses to dazzling effect--especially in his evocative and detailed descriptions of characters and settings. The phrases seem to be tossed effortlessly onto the page, but they struck me as so beautiful that I whipped out my highlighter pen. That pen nearly ran out of ink before I finished the book. Here are just a few of my favorite passages, thrown at you out of context but I think they stand alone just fine as individual gems.

He talked in the slow, careful manner of a man chewing cactus.

Outside the birds began singing like hundreds of small bells, their notes scattered as indiscriminately as seed.

....sex smelled a lot like tossed salad, one with radishes, fennel, and fresh grated carrot, and maybe a tablespoon of scallions thrown in.

A man of medium height, with brisk, officious eyes and the cinematic mustache he’d worn in the army, the pencil-thin wisp like an advertisement for how well the world should think of him.

....to the sort of serious, no-frills neighborhood bar where the walls sweat tears of nicotine and the waitresses have the grizzled look of ex–child brides.

And then these sentences from the collection's final story, "Fantasy for Eleven Fingers," which opens with a biography of Anton Visser, a fictional 19th-century composer who

played the piano like a human thunderbolt, crisscrossing Europe with his demonic extra finger and leaving a trail of lavender gloves as souvenirs. Toward the end, when Visser-mania was at its height, the mere display of his naked right hand could rouse an audience to hysterics; his concerts degenerated into shrieking bacchanals, with women alternately fainting and rushing the stage, flinging flowers and jewels at the great man.Visser composes the titular Fantasy, which is called “a most strange and affecting piece, with glints of dissonance issuing from the right hand like the whip of a lash, or very keen razor cuts.”

The story is perfect companion piece to Billy Lynn's Long Halftime Walk in the way it portrays the mass hysteria of a phenomenon (a child prodigy pianist, a war hero) which no one can understand. I believe Fountain truly cares about his objects of scorn--the lemmings of society who blindly follow a bullheaded president into a misguided war, for instance--and that he wants, more than anything, for his readers to wake up from their slumber of indifference. In both books, the bark of the whip leaves small, lasting razor cuts across our backs.

OK, this book needs to move up the priority list in my to-read column. It's been there since it came out, but I think I'm at a place where it would really resonate. I teach an Intro to Mass Media course at the local university, and it sounds like this book touches upon so much of what we discuss--the government PR machine, carefully crafted narratives of "hero," the inability to look beyond the surface of what we see on TV or read in the newspapers.

ReplyDeleteDid you read the profile of Fountain in the April edition of Poets & Writers? His story is fantastic--the writer who toils away for years, almost gives up, but then comes out with this gem.

All the NBA nominees were wonderfully deserving, but I take some pride in that two of the winners live in Minnesota :)

I must inform you, with some sorrow, that the game featured in the novel is NOT a Super Bowl game; it is the annual Thanksgiving game that the Cowboys play. Although the Cowboys did host a Super Bowl two years ago, it was not at the crumbling Texas Stadium featured in the novel, but the shiny new spaceship-looking-thing in Arlington. And - this is where the sorrow comes in - the Cowboys did not play in that game. The Super Bowl that year featured their arch-rivals, the Pittsburgh Steelers, and the victorious Green Bay Packers (another ancient foe). The Cowboys have not played in the Super Bowl in lo these many years, to my shame and embarrassment.

ReplyDeleteYou know what, Curtis--you are absolutely right. Why I never put two and two together before--i.e., that the game is played at Thanksgiving--I'll never know. Thanks for bring this to my attention. I'll make that fix right away.

ReplyDeleteChalk it up to the fact that I'm pretty ignorant when it comes to sports.