Wednesday, September 13, 2017

The Marriage of Shelves: Jay Baron Nicorvo’s Library

Reader: Jay Baron Nicorvo

Location: Battle Creek, Michigan

Collection Size: About 2,000

The one book I’d run back into a burning building to rescue: My MacBook Pro. On it is everything! I’d suffer burns on 38 percent of my lower body to save the early starts I have on a new novel and a memoir.

Favorite book from childhood: My Storybook Dictionary

Guilty pleasure book: My own. I’m sorry, but here we are a few months post-publication and I still have a hard time believing my novel indeed made it onto shelves, that I did in fact write it, and that someone from St. Martin’s isn’t going to steal into my house, repo all my copies, and leave a note on company letterhead saying the whole thing was a terrible misunderstanding, but it wasn’t their fault, it was mine.

I’m fascinated by literary couples. Part of the compulsion is tabloid—I was crushed when Paul Lisicky and Mark Doty split; no book made me sob harder than The Best Day the Worst Day, Donald Hall’s memoir of the life he shared with Jane Kenyon before her death—but some of my interest is logistical.

For instance, when two writers move in together, how in hell do they organize their respective libraries? Is there a trial period of shelf separation—yours, mine—before a ceremonial marrying of the titles? Two well-suited people will surely share some redundancy. What’s to be done with the doubles when shelf space, as it’s bound to, gets scarce? Whose copy is kept? And why? Oh, I see, yours is signed. But so’s mine.

Thisbe Nissen and I met at a writers conference and, a year later, we got engaged at said conference (during my introduction to her reading, I slipped in an on-stage, down-on-bended-knee proposal). When we bought our first house, outside Saugerties, New York, in the foothills of the Catskills, among the first things we did was have bookshelves built. A few years later, when we sold that house and decamped for the Midwest, before we set up our son’s bedroom or renovated the handicapped shower stall in the bathroom—the previous owner was paraplegic—we had bookshelves built.

Thisbe and I merged and purged at the very beginning. But we did decide, for reasons now lost to me, to segregate by genre—poetry from prose. This meant that when my first book, a collection of poems, was published, it got proudly sandwiched between Aimee Nezhukumatathil’s Lucky Fish and Nila NorthSun’s Diet Pepsi & Nacho Cheese. But it was far removed from Thisbe’s books of fiction.

Our poetry ghetto. You should be able to see that the Bible is shelved here, alphabetized under G, and at some point Sonne, too, got shelved in poetry. He was just learning to talk then—what a lyrical time. These days, at age seven, his yammering tends more toward prose, but for a wordy kid he’s rarely prosaic.

In our library sits my desk (Thisbe has her own office) which I made from the flooring of a collapsed barn, after planing off the manure, and old porch posts that flake lead paint I try not to eat. Or snort. Over my desk hangs a digitally altered image, in the style of Shepard Fairey, made for me by my brother Dane. The distorted photo is of that uxoricidal addict William S. Burroughs, which I can’t bring myself to shove in a closet. Seems unjust, after what Burroughs went through to get out. I have little loyalty to Old Bull Lee. If anything, I’m drawn more toward his son, William S. Burroughs Jr., 4 years old when his father shot his mother, poet Joan Vollmer, and dead in Florida at age 33, having published two novels, Speed and Kentucky Ham, sometimes misattributed to his deadbeatnik dad. If, like WSB Sr., you’re closeted and you’re married, there are better ways to go about outing yourself than aiming low at the water glass balanced on your wife’s head, but those were, in some ways I suppose, tougher times.

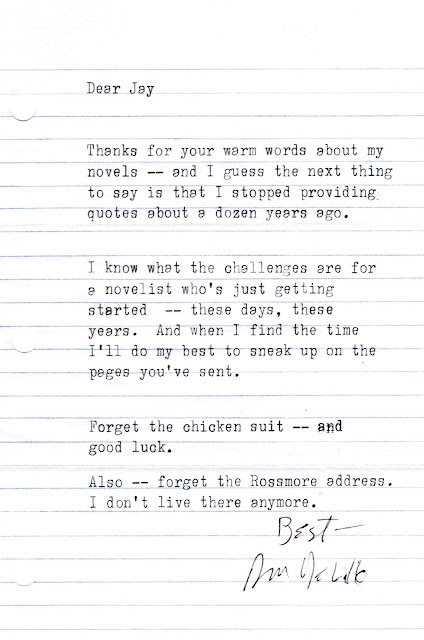

Consider me guilty of harboring the old-school misogynist, little reassured by Patti Smith’s sentiments expressed in Just Kids: “William Burroughs was simultaneously old and young. Part sheriff, part gumshoe. All writer. He had a medicine chest he kept locked, but if you were in pain he would open it. He did not like to see his loved ones suffer. If you were infirm he would feed you. He’d appear at your door with a fish wrapped in newsprint and fry it up. He was inaccessible to a girl but I loved him anyway.” So Burrows looks ever down on me as I write because I love my brother and, too, because Junky, I must admit, was a formative book for me during a drug-addled time. Among the other photos and tchotchkes on my desk—severed foot of a barred owl, anyone?—is a framed letter from Don DeLillo advising me to “forget the chicken suit.” No explanation necessary.

Shelved over the window is just about everything I’ve even written, in draft, printed out and stacked sidelong in chronological order. On the far left is the first creative writing I did at age eighteen. I have no want to look and see what that might be. Likely some functionally illiterate dreck I turned in for a community-college class in Bradenton, Florida. At the far right, 22 years later, is a draft of the last thing I wrote, this.

When my first novel was published earlier this year, my proudest moment was not the generous endorsements from this or that long-idolized writer, nor the call from my editor to tell me my first review earned a star, not the launch reading at Bookbug, the local independent bookstore, or making some fancy list or other. My proudest moment was a quiet one. My box arrived in the mail and I climbed our stairs to our library with a copy. I made room on the alphabetized prose shelf and, thanks to the lucky nearness of our surnames, tucked my novel in beside Thisbe’s. You can see here the galley for her forthcoming novel, Our Lady of the Prairie, rubbing up against The Standard Grand. I like to think we’re inseparable. That is, unless we buy a copy of Thus Spake Zarathustra by Nietzsche. That or Sonne—whose last name is an unprecedented portmanteau, illegal in the state of Tennessee, of our last names, Niscorvosen—one day publishes a book of his own. We can only hope it isn’t poetry.

Jay Baron Nicorvo is the author of a novel, The Standard Grand (St. Martin’s Press), picked for IndieBound’s Indie Next List, Library Journal’s Spring 2017 Debut Novels Great First Acts, and named “New and Noteworthy” by Poets & Writers. He’s published a poetry collection, Deadbeat (Four Way Books), and his nonfiction can be found in Salon, The Baffler, The Iowa Review, and The Believer. He lives on an old farm outside Battle Creek, Michigan, with his wife, Thisbe Nissen, their son, and a couple dozen vulnerable chickens. Find Jay at www.nicorvo.net.

My Library is an intimate look at personal book collections. Readers are encouraged to send high-resolution photos of their home libraries or bookshelves, along with a description of particular shelving challenges, quirks in sorting (alphabetically? by color?), number of books in the collection, and particular titles which are in the To-Be-Read pile. Email thequiveringpen@gmail.com for more information.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.