Saturday, October 13, 2012

The Chaos Theory of Marriage: Brand New Human Being by Emily Jeanne Miller

Brand New Human Being

by Emily Jeanne Miller

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

Guest review by Andrea Kinnear

Most marriages follow one path, one set of deliberate decisions that must be followed to guarantee the success and sanctity of marriage. It is this one true path that is traversable, seemingly, only in the ideal. I have yet to witness a married couple actually staying on said path throughout their marriage. One single, minuscule misstep takes the spouse off the yellow brick road to marital Oz and into the clutches of the flying monkeys. Some couples, like Dorothy and her companions, survive the seemingly impossible obstacles to find their way home; many do not.

Like the proverbial butterfly flapping its wings in China and causing Hurricane Andrew to devastate Miami, relationships have their own Chaos Theory. One millimeter five degrees to the left, repeated five hundred times, can send a marriage into divorce court with contested custody. Where did the collective “we” go wrong? It was the scowl over breakfast ten years ago that yielded my offense, that drew your derogatory response, that raised my voice, that… Each comment ups the ante, and when the process repeats over years, the hurt and damage amplify.

Meet Logan and Julie Pyle in Brand New Human Being, the debut novel by Emily Jeanne Miller. These two virtually prove Marital Chaos Theory: a series of seemingly small decisions--a moment here, a habit there, a reaction to this--drive the spouses very distantly off course. Add in some significant stressful life events, a first-born child, a death of a family member, a demanding career, and the course appears uncorrectable. I spent the first two hundred pages beating my head against the book. I silently screamed, “No, no, no!” every time Logan or Julie spoke a word.

The struggles in the Pyle marriage are very real, very plausible, and in some ways very terrifying. The Pyles are the poster children for every marriage as they expose thousands of impulse decisions that can easily lead to disaster. Miller takes their marital chaos and makes a powerful case for course correction, even after a ravaging storm. In her book, she provides a fresh landscape for nearly universal marital and parental struggles. I found myself disturbed, angered, and ultimately inspired by the characters in her swift and accessible Brand New Human Being.

My range of emotion grew from my identification with wife and mother, Julie Pyle. How many times have I placed the kids above the marriage? The scientific answer is TNTC = too numerable to count. How many times have I made a major decision about the children without consulting my husband? Well, maybe not as frequently as the former question, but the answer is somewhere close to, but less than, countless. How many times has my husband very courageously called me out on my maternal myopia? Well, the numbers dramatically shrink to an N of 2. (And I can assure you the, ahem, conversations, were so civil as to deter their repetition.) Maternal myopia is so attractive, so instinctive, so easy. I won’t draft the opposing paragraph in my husband’s voice, but my confidence is high that he would say his life, like that of Logan Pyle, is “nothing like I thought it would be.”

But before the graph spikes over Julie’s name, Brand New Human Being highlights the significance of the number 2. Marriage is a set with no fewer, no more, than two. Two people take a vow, and only two people can dissolve the union. Two people conceive a child, and optimally, two parents raise this human being. When the graph of either the marriage or the parenting negatively slopes, only two people, working from a union of previously disparate sets, can change the equation of the line. What is important to note, is that this equation can be changed – even in the presence of a brand new human being.

Andrea Kinnear is a math aficionado and avid bibliophile. She blogs about equations and books at Faulkner 2 Fibonacci.

Friday, October 12, 2012

Friday Freebie: The Yellow Birds by Kevin Powers

Congratulations to Doni Molony, winner of last week's Friday Freebie: The Lighthouse Road by Peter Geye.

This week's book giveaway is The Yellow Birds by Kevin Powers. I'm especially pleased to offer this novel about the Iraq War to Quivering Pen readers. As I mentioned earlier, I did a series of fist-pumps when I learned The Yellow Birds (along with Billy Lynn's Long Halftime Walk by Ben Fountain) had been named as a finalist in this year's National Book Awards. I've been a champion of Powers' book ever since I finished reading an advance copy of it in August. It's lyrical, it's profound, and it will break your fucking heart. It belongs on the same shelf as Ernest Hemingway and Tim O'Brien and I completely agree with Ann Patchett who said the novel is "harrowing, inexplicably beautiful, and utterly, urgently necessary." Here's the basic plot summary (which doesn't do full justice to the beauty of the book):

In Al Tafar, Iraq, twenty-one-year old Private Bartle and eighteen-year-old Private Murphy cling to life as their platoon launches a bloody battle for the city. Bound together since basic training when Bartle makes a promise to bring Murphy safely home, the two have been dropped into a war neither is prepared for. In the endless days that follow, the two young soldiers do everything to protect each other from the forces that press in on every side: the insurgents, physical fatigue, and the mental stress that comes from constant danger. As reality begins to blur into a hazy nightmare, Murphy becomes increasingly unmoored from the world around him and Bartle takes actions he could never have imagined.As further proof of Powers' artistry, here are the opening paragraphs of The Yellow Birds:

The war tried to kill us in the spring. As grass greened the plains of Nineveh and the weather warmed, we patrolled the low-slung hills beyond the cities and towns. We moved over them and through the tall grass on faith, kneading paths into the windswept growth like pioneers. While we slept, the war rubbed its thousand ribs against the ground in prayer. When we pressed onward through exhaustion, its eyes were white and open in the dark. While we ate, the war fasted, fed by its own deprivation. It made love and gave birth and spread through fire.If you'd like a chance at winning a copy of The Yellow Birds, all you have to do is email your name and mailing address to thequiveringpen@gmail.com

Then, in summer, the war tried to kill us as the heat blanched all color from the plains. The sun pressed into our skin, and the war sent its citizens rustling into the shade of white buildings. It cast a white shade on everything, like a veil over our eyes. It tried to kill us every day, but it had not succeeded. Not that our safety was preordained. We were not destined to survive. The fact is we were not destined at all. The war would take what it could get. It was patient. It didn’t care about objectives, or boundaries, whether you were loved by many or not at all. While I slept that summer, the war came to me in my dreams and showed me its sole purpose: to go on, only to go on. And I knew the war would have its way.

Put FRIDAY FREEBIE in the e-mail subject line. One entry per person, please. Despite its name, the Friday Freebie runs all week long and remains open to entries until midnight on Oct. 18—at which time I'll draw the winning name. I'll announce the lucky reader on Oct. 19. If you'd like to join the mailing list for the once-a-week Quivering Pen newsletter, simply add the words "Sign me up for the newsletter" in the body of your email. Your email address and other personal information will never be sold or given to a third party (except in those instances where the publisher requires a mailing address for sending Friday Freebie winners copies of the book).

Want to double your odds of winning? Get an extra entry in the contest by posting a link to this webpage on your blog, your Facebook wall or by tweeting it on Twitter. Once you've done any of those things, send me an additional e-mail saying "I've shared" and I'll put your name in the hat twice.

Thursday, October 11, 2012

Fobbit Tour: Montana Festival of the Book

I walked into the room where I was about to read from Fobbit and saw my wife sitting with another man. He was handsome, bearded, and seemed to be having a very intimate conversation with my wife.

It took my brain a few seconds to catch up to my eyes before I realized that was my son. My SON!! What was he doing here in Missoula at the Montana Festival of the Book when he should be back in Savannah, Georgia where he's enrolled as an art student?

After a series of breath-robbing hugs, I learned that Jean had flown Deighton out here as a surprise for me (as well as to brighten her own days while I was out on the road promoting my debut novel). And what a surprise it was! I'd just flown in to Missoula from Seattle and while I'd previously arranged to meet Jean at my reading, I had no idea she'd have my son in tow.

The book festival, sponsored by Humanities Montana, has been one of the highlights of my year since I moved back to Big Sky Country in 2009. But this--this was icing on the frosted cake. Unless he's able to make it to my appearance in Atlanta later this month, I knew this was probably the only time Deighton would hear me read from Fobbit. I chose the opening from Chapter 2--a section I'd never before read publicly, but which Jean had told me was one of her favorite passages from the book.

This was not good.

With Iraqis pressing around him on all sides like circus spectators leaning forward to see the man on the high-wire act slip and tumble, Lieutenant Colonel Vic Duret looked through his field glasses at the man slumped in the driver’s seat. The man should be dead by now but he was still breathing and every so often his shoulders gave barely-perceptible twitches.

This was definitely something to be filed under Not Good.

As far as I could tell, my first event at the festival was Good; and while I appreciate all the other people who were there with me in that room, I was really reading for one person that day.

Deighton and I spent the rest of the weekend together, strolling through downtown Missoula's First Friday art walk, eating breakfast at The Catalyst, hiking to the "M" (okay, hiking one-third of the way to the "M"), and attending readings and panels at the book festival. I couldn't have asked for a better three days. Unless my other two children showed up. But then I would probably have burst into sobs. And that is so unbecoming.

* * *

At my reading, I was paired with Kim Barnes, author of the memoirs In the Wilderness: Coming of Age in Unknown Country and Hungry for the World and the novels A Country Called Home and Finding Caruso. Her newest novel, In the Kingdom of Men, proved to be a good companion piece to Fobbit. In the Kingdom of Men is set in Saudi Arabia in the late 1960s and follows a young wife as her husband takes a job with an oil company and they live in a confined, gated community in the desert. Both of our novels are about strangers in a strange land--Americans encountering a culture clash with the Middle East. Kim's novel also has a great, hooky opening:

Here is the first thing you need to know about me: I’m a barefoot girl from red-dirt Oklahoma, and all the marble floors in the world will never change that.Kim and I were also part of a panel, moderated by the affable and unflappable John Clayton, in which we discussed the relevance of setting in our novels. We were joined by Alyson Hagy and Jess Walter who talked about their landscapes of Wyoming, California, Italy, and Hollywood. So, our novels covered enough territory to keep a cartographer busy for several hours. A lot of smart, funny things were said during that panel (most of them by Kim, Alyson and Jess).

Here is the second thing: that young woman they pulled from the Arabian shore, her hair tangled with mangrove—my husband didn’t kill her, not the way they say he did.

* * *

The rest of the festival was a blur and, atypically for me, I forgot to write anything down in the small notebook I keep in my back pocket. Consequently, thanks to an increasingly faulty memory (aka Swiss-Cheese Brain), I'm left with only the impression of stacks of books in the festival bookstore in the hotel's atrium, a long succession of handshakes (some from friends congratulating me on Fobbit's publication, some from authors I was meeting for the first time--writers like J. Robert Lennon, Pam Houston, emily danforth, Charles Finn, Tami Haaland, Lowell Jaeger, Joe Wilkins and Jess Walter), and a falcon perched on the arm of Kate Davis who was there to promote her book Raptors of the West. I had just enough time to take in a panel on the "road novel" with Houston, Lennon, Jonathan Evison and Patrick deWitt; a screening of clips from the upcoming movie of James Welch's Winter in the Blood; and readings by Lennon (from his new novel Familiar), Alyson Hagy (who read a poignant passage about death from her new novel Boleto), danforth (from The Miseducation of Cameron Post), and Walter (who opted not to read from his new novel Beautiful Ruins, but shattered the crowd with a short story from his forthcoming collection; you can go online and read "Statistical Abstract for My Home of Spokane, Washington" for yourself, but you won't get the full effect of the emotion choking Walter's voice as he reached the final line of the story--absolutely devastating).

* * *

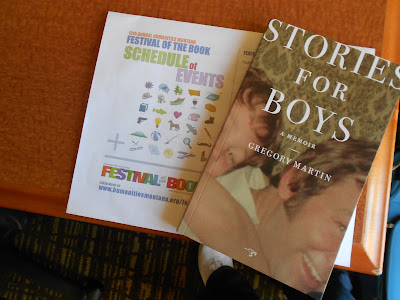

Despite the many attractive pieces of book-fruit hanging from the trees here at the festival, I limited myself to one book and one book only (my suitcase already has that "Unbearable Heaviness of Books" feeling to it). Stories for Boys by Gregory Martin was an easy choice after meeting the author at the festival's opening reception, hearing a little bit of his story, then reading the opening pages of the memoir. I'll leave you with the first few paragraphs from Chapter 2:

On Thursday, May 3rd, 2007, at about six in the evening, in Spokane, Washington, my mother and father had a fierce argument. Fights and conflict were rare for them, and never lasted long. They'd been married thirty-nine years. They had a happy marriage. My father said, "If you want me to go, then I'll really go." He went upstairs. A few minutes later, my mother followed. She found him sitting on the end of their bed, his eyes unfocused, his head and shoulders sagging. "What did you do?" she shouted. "I took some pills," my father answered. "You won't have to worry about me anymore." My mother went into the bathroom. All the bottles from the medicine cabinet, a pharmacy's worth of drugs including the Ativan and Trazodone my mother took for bipolar disorder, were out and open and empty on the counter. She called 911.

The last thing my father ever wanted was to be a character in a melodrama. He did not want to step on stage at sixty-six, his hair gray, a small paunch over his belt, and play the tragic lead. He wanted to drink Coca-cola and watch Jeopardy! and listen to the Kingston Trio, to bowl and play cribbage with my mother, to read science fiction novels and watch movies with explosions, to work as a speech pathologist in a nursing home, helping the elderly to speak again and swallow soft foods like yogurt and rice pudding.

Two days later, on the fifth floor of the psychiatric ICU of Spokane's Sacred Heart Hospital, after my father had spent thirty-six hours in a coma on a ventilator, the intubation tube was removed from his throat. His head back on his pillow, his eyes closed, his face pale, he slowly regained consciousness. He recognized me as I gripped his hand, touched his forehead. The agony etched on his wrinkled face was clear. He did not want to be alive.

Wednesday, October 10, 2012

Iraq War fiction and the National Book Awards

It's a great day for Iraq War fiction.

I was delighted to see The Yellow Birds by Kevin Powers and Billy Lynn's Long Halftime Walk by Ben Fountain were both named as finalists for this year's National Book Awards. I've read both novels and believe they are important additions to the national dialogue on our most recent conflicts in the Middle East. Powers writes a sobering, haunting account of one soldier's experience on the battlefield and the struggle to fit in to life in the United States after his return. Fountain's novel matches The Yellow Birds in intensity, but it's on the other end of the spectrum: wickedly delicious satire. Billy Lynn's Long Halftime Walk centers around a squad of soldiers who are brought back, mid-war, to be celebrated as heroes at the Super Bowl halftime. Nothing against the other nominees--Junot Diaz, Dave Eggers and Louise Erdrich (whose books I have yet to read)--but I'm secretly pulling for the Iraq War candidates to win.

Here's the complete list of the National Book Award finalists:

Fiction

This Is How You Lose Her by Junot Diaz

A Hologram for the King by Dave Eggers

The Round House by Louise Erdrich

Billy Lynn's Long Halftime Walk by Ben Fountain

The Yellow Birds by Kevin Powers

Non-Fiction

Iron Curtain: The Crushing of Eastern Europe, 1945-1956 by Anne Applebaum

Behind the Beautiful Forevers: Life, Death, and Hope in a Mumbai Undercity by Katherine Boo

The Passage of Power: The Years of Lyndon Johnson, Volume 4 by Robert A. Caro

The Boy Kings of Texas by Domingo Martinez

House of Stone: A Memoir of Home, Family, and a Lost Middle East by Anthony Shadid

Poetry

Bewilderment: New Poems and Translations by David Ferry

Heavenly Bodies by Cynthia Huntington

Fast Animal by Tim Seibles

Night of the Republic by Alan Shapiro

Meme by Susan Wheeler

Young People's Literature

Goblin Secrets by William Alexander

Out of Reach by Carrie Arcos

Never Fall Down by Patricia McCormick

Endangered by Eliot Schrefer

Bomb: The Race to Build—and Steal—the World's Most Dangerous Weapon by Steve Sheinkin

Congratulations to all the finalists!

You can learn more about the finalists, other honrees and the National Book Awards in general at its website.

Tuesday, October 9, 2012

Fobbit Tour: University Bookstore in Seattle

One of the greatest sights I've seen so far on this cross-country book tour for Fobbit was when Joe C., a family friend I haven't seen in about 35 years, showed up for the reading in Seattle with a copy of the novel which looked like it had been through a war itself. The spine was creased and curved like it had been propped open face-down at many points as Joe made his way through the story. There was a dark grey scuff mark on the cover, as if it had fallen to the floor of a car and someone had accidentally stepped on it. I wouldn't be surprised if there were food stains on a few of the pages.

These are the signs of life every writer likes to see running like traffic through his or her book.

It's especially gratifying to me because Fobbit has only been on the streets for about five weeks (in Joe's case, it looked like it had literally been on the street). Nearly every other copy of the book has been in pristine condition, so it was nice to see proof that someone had actually read the book.

The second thing which delighted me at the October 4 reading at University Bookstore was the surprise appearance of my nephew Tyler. I hadn't seen him in years, so it was a nice treat to have him out there in the audience (along with several e-friends--Cat, Matt, and Jim--I was meeting for the first time). Tyler proudly serves in the U.S. Air Force. But I don't hold that against him.

|

| This is me, trying not to embarrass myself with fanboy love for Karl. I probably failed. |

I was joined at the Seattle reading by fellow Grove/Atlantic author Karl Marlantes who had several nice things to say about Fobbit--all of which I promptly forgot due to the excited hum in my ears (yes, yes, I was experiencing a bit of fanboy euphoria sitting next to this writer I'd revered for years [Karl and I met for the first time the previous weekend when we were in South Dakota]). I'm a long-time admirer of his novel about Vietnam, Matterhorn, and I'm of the firm opinion that his second book, What It Is Like To Go To War, should be required reading for every member of the Armed Forces. (It occurs to me that I've probably said this before.....but hell, it bears repeating). Karl and I spent the better part of an hour discussing the impact war had on our lives as well as the different approaches we took to committing our experiences to the page.

My sincere thanks to Karl, Tyler, my e-friends, and Joe with his bruised and battered Fobbit for making it a tremendous evening.

Monday, October 8, 2012

My First Time: George Singleton

My First Time is a regular feature in which writers talk about virgin experiences in their writing and publishing careers, ranging from their first rejection to the moment of holding their first published book in their hands. Today’s guest is George Singleton, one of the funniest writers north or south of the Mason-Dixon Line. His newest collection of short stories, Stray Decorum, has just been released by Dzanc Books. Singleton’s other story collections are These People Are Us, The Half-Mammals of Dixie, Why Dogs Chase Cars, and Drowning in Gruel; his two novels are Novel and Work Shirts for Madmen. Most recently he has published a guide for writers titled—in wry Singletonian fashion—Pep Talks, Warnings, and Screeds: Indispensable Wisdom And Cautionary Advice For Writers. His stories have appeared in The Georgia Review, Atlantic Monthly, Harper’s, Playboy, Zoetrope, Shenandoah, Southern Review, Kenyon Review, Glimmer Train, North American Review, Epoch, and New England Review, among others. Singleton has taught English and fiction writing at Francis Marion College, the Fine Arts Center of Greenville County, and the South Carolina Governor’s School for the Arts and Humanities, and has been a visiting professor at the University of South Carolina and UNC-Wilmington. A 2009 Guggenheim Fellow, he lives in Pickens County, South Carolina, with the clay artist Glenda Guion and a number of stray dogs and one cat.

My First Stet

At some point in 2006 my great copyeditor at Harcourt, David Hough, called to say, “My mom’s sick back in Minnesota, and I need to go back there. I’ve hired out another copyeditor to look over Work Shirts for Madmen.”

Of course I said, “Yes. No problem. Good God, buddy, go take care of your mom.”

David said, “Listen, this woman who’s going to copyedit--she’s old, and from New York. When I get back, we’ll look over her suggestions.”

“Get going, man, get going,” I said.

David Hough sounded like Harvey Fierstein over the telephone, as if he gargled with roofing nails. In the previous two books he put up with my characters saying things like “I ain’t got no money,” for he knew what they meant. He put up with “y’all” and “fuckin A” and “Hey, buddy, you got a case quarter I can borry?” even though neither of us knew the meaning or origins of “fuckin A” or “case quarter.” David pretty much called and said, “You meant that to be ‘possum’ on page 227, instead of ‘opossum,’ right?”

I don’t know if any of those slick editing systems with all the margin queries and whatnot had been invented in 2006, but the subcontracted copyeditor for Work Shirts for Madmen sent me back a hard copy of the manuscript. She must’ve spent fifty bucks in red pencils. I went through writing “Stet...Stet...Stet” oh, on average, twenty times per page.

Evidently I have a tendency--or my characters have a tendency in first-person narration--to say things like “I only want to hit the couch and take a nap,” or “I only want for my wife to quit starting projects that require my assistance,” or “I drink moonshine only in Kentucky.”

The copyeditor woman changed the first one of these sentences to “I want only to hit the couch...” and “I want only for my wife” and “I drink moonshine in Kentucky only.”

On the third one of these changes she found it necessary to point out in the margins, “Do you people in the South not know this grammar rule?”

Stet. Stet. Stet.

On the fourth instance of her changes I wrote in the margin, “I want only to kill you.”

I sent the manuscript back to David and, when he returned from Minnesota he called me up and said something like, “I had a feeling that wasn’t going to work out all that well. Don’t worry, I’ve gone back and made sure we have your original voice.”

In the Acknowledgements for that particular novel I had thanked my editor/publisher, agent, David Hough, and so on. I had put in there, too, “I want only to thank...” whatever the Old School grammarian woman’s name was. Someone took that part out, though, when the book finally got published.

I have nothing else to do in Dacusville, South Carolina except be mean and think up tricks, so I started a slew of stories wherein the main character’s name was Stet. What the hell. I thought it would be funny to have “Stet” all over the text, and then--should I ever get another subcontracted copyeditor--I could also write “Stet” all over the margins. I wrote something like thirty-five of these stories, sometimes when Stet Looper was narrating, sometimes when he miraculously appeared as a minor character. Wait--it’s probably supposed to be “...sometimes when he appeared miraculously as a minor character.”

Anyway, the original collection of Stray Decorum was something like 450 pages. It got cut in half, wisely, by my agent. After Stray Decorum, the other section of Stet stories will come out in 2014. It’s called No Cover Available--and I have a story about that, which has to do with New York publishers wanting to put confederate flags on my covers, or flamingos that don’t live in South Carolina, and so on.

Anyway, that’s the reason for the Stet stories. I only wish I knew that woman’s name, so I could thank her. Kind of.

Friday, October 5, 2012

Friday Freebie: The Lighthouse Road by Peter Geye

Congratulations to Jane Rainey, winner of last week's Friday Freebie: Panorama City by Antoine Wilson.

This week's book giveaway is The Lighthouse Road by Peter Geye. Just published this week by Unbridled Books, The Lighthouse Road is a novel that, as Booklist puts it, brings the wilderness of northern Minnesota "to crackling, thundering life." Here's the plot summary of the book:

In 1895 Thea Eide leaves her arctic home in Norway for a better life in America. After a harrowing journey, she arrives in Gunflint, Minnesota, expecting to find her aunt and uncle and the life she was promised. What she finds instead is an enormous wilderness and a village full of strangers. Twenty-four years later, her son, Odd, is cobbling together a life of his own. A fisherman, boatbuilder, and bootlegger, all he wants is his fair share. When he and Rebekah Grimm, a woman as much his sister as his lover, are forced to flee Gunflint in Odd’s newly built boat, they leave behind the only world Odd has ever known. Told in alternating and parallel narratives, The Lighthouse Road explores the themes of love and family and what it means to live an honest life in a suspect world.Benjamin Percy--who knows a thing or two about muscular sentences--had this to say about The Lighthouse Road: "Peter Geye writes with the mesmerizing power of the snowstorms that so often come howling off Lake Superior. I am in awe of how he swirls through so many years and juggles so many characters, all of them unforgettable and weighed down by secrets and regrets and desires that burn through the hoarfrost of Geye's bristling sentences."

Now, if you'll excuse me, I'll step out of the way and let the novel speak for itself. Here's an excerpt from the book to give you a taste of what awaits you in its pages (I just love the last sentence of this passage):

The Port av Kristiania arrived at her final destination in the middle of the night. Thea was sleeping in her bunk when she felt the ship’s definitive stop. She found her bags and joined the crowd and by the time she reached the main deck she was wide awake and consumed by a new awe: Kristiania—even at night, perhaps especially at night—sprawled all around her. The gas streetlamps flickered near and far, those on the yonder hillside a kind of greasy mirage that might not have been light at all, might have been only an impossible reflection. There were warehouses on the waterfront three times larger than the ship she was now stepping off. Everywhere the sounds of harbor life thrummed: the grinding and shrieking of train and trolley tracks, the clatter of horses’ hooves on the dock’s planks, the moaning of loading cranes, and above and below all of it the sound of human voices.

Before then, Thea had never seen more than one hundred people gathered together. But even in the middle of the night there were thousands of people here. In the next slip two steamships, each twice as long as the Port av Kristiania, were loading, crowds of people tunneled into the shadowy quay. As Thea reached the gangplank, she noticed the taut ship lines crisscrossing the docks, the enormous nets hauling cargo onboard the steamships before her, and casks by the thousands ready to be loaded into ships’ holds.

As soon as she was on the dock she was swept into a cordoned area where several nurses stood ready to examine and interrogate the passengers. One at a time they were led to tables. When it was Thea’s turn, a grim-faced woman signaled her to come forward. Thea was asked to provide her ticket for passage. The nurse confirmed the ticket against a list in her passenger log and proceeded to ask a series of twenty-nine questions.

Aside from the routine questions regarding her final destination and place of birth and the promise of labor in America, she was also asked whether or not she was an anarchist or polygamist, if she was in any way crippled or had deformities, if she had ever been imprisoned. She spent fifteen minutes answering these and other questions, and when the interview was complete, the nurse took Thea into a curtained area and asked her to remove her cloak and hat.

The medical examination that followed was cursory. After the nurse listened to Thea’s lungs with her stethoscope and checked her for a hunchback and diseases of the skin, she filled out a landing card and told Thea she could go aboard Thingvalla. As she ascended the steep gangplank, she could already feel the melancholy sea in the soles of her feet.

If you'd like a chance at winning a copy of The Lighthouse Road, all you have to do is email your name and mailing address to thequiveringpen@gmail.com

Put FRIDAY FREEBIE in the e-mail subject line. One entry per person, please. Despite its name, the Friday Freebie runs all week long and remains open to entries until midnight on Oct. 11—at which time I'll draw the winning name. I'll announce the lucky reader on Oct. 12. If you'd like to join the mailing list for the once-a-week Quivering Pen newsletter, simply add the words "Sign me up for the newsletter" in the body of your email. Your email address and other personal information will never be sold or given to a third party (except in those instances where the publisher requires a mailing address for sending Friday Freebie winners copies of the book).

Want to double your odds of winning? Get an extra entry in the contest by posting a link to this webpage on your blog, your Facebook wall or by tweeting it on Twitter. Once you've done any of those things, send me an additional e-mail saying "I've shared" and I'll put your name in the hat twice.

Thursday, October 4, 2012

"Thaw," an excerpt from Glaciers by Alexis M. Smith

Sometimes you find the book, and sometimes the book finds you. This was the case for me when, earlier this year, I walked into the Barnes and Noble in Bozeman, Montana "just to get a latte" (i.e., I wasn't on a typical book-buying mission). I was walking toward the cafe when it happened: Glaciers found me. It was like one of those "meet cute" scenes in movies when the pretty brunette dogwalker and the distracted guy with the briefcase, walking in opposite directions, round a corner at the same time and he ends up tangled in leashes and tails and she knocks the briefcase out of his hand, spilling papers all over the sidewalk. That's how it was for me with Alexis M. Smith's slim, pretty novel. A chance encounter. A walking past, then a double-take and a doubling-back. A glance at the cover. A skim of the plot summary, blurbs and first sentence ("Isabel often thinks of Amsterdam, though she has never been there, and probably will never go."). An eye-poke of interest. An impulse buy.

It was the best thing I bought all year (and that includes the 2011 GMC Acadia my wife and I just purchased).

The novel chronicles one day in the life of Isabel, a twenty-eight-year-old library worker, as she repairs damaged books, prepares for a party, and pines for a co-worker, an Iraq War veteran named "Spoke." As a single woman living in Portland, Oregon, Isabel haunts thrift stores and collects second-hand items like postcards, teacups, aprons, dresses--the cast-off remnants which were once new, happy purchases by someone decades earlier. "She feels a need to care for them that goes beyond an enduring aesthetic appreciation," Smith writes. "She loves them like adopted children."

It's fitting that Isabel collects scraps of the past because she is a character who lives primarily in memory. The book slips seamlessly between the present and Isabel's childhood growing up in Alaska and Portland with her mother, father and sister Agnes. Written in sentences as simple and delicate and beautiful as a single strand of a spider's silk, Glaciers reads like a literal dream. We move through the pages quickly, as if floating just above the words, and it's over before we want it to be. I could have stayed in Isabel's world for a long, long time.

Glaciers is easily one of the best books I've read this year. It's beautifully packaged by Tin House Books--French flaps, deckle-edge pages, generous white space around the text--and even more gorgeous, sentence by sentence, chapter by chapter. I was so impressed by Smith's writing that I emailed her and asked if I could reprint one of those chapters, "Thaw," here at the blog. Happily, she said Yes; and so, with the publisher's permission, here is just one of the many stunning shards of Glaciers.

Thaw

When Isabel was small, her father worked on the North

Slope for what seemed like months at a time. It was actually two weeks on, two

weeks off, but time seemed to go on longer then.

In the winter, the Slope was a dark, starry

place, with a colony of busy fathers working in the snow and ice. In the

summer, the light never ended, and they measured one hour to the next by the

beeps on their digital watches, eating periodically from vending machines.

Isabel knew about the vending machines because when her father came home he

always brought a candy bar for Agnes and Isabel to share.

The girls couldn’t sleep summer nights, because of the

light slipping in from outside. And on nights when their father was coming

home, they waited up for him and the candy bar. She remembers running into his

arms; the cold petroleum smell of his work clothes.

But when they asked questions about where he had been and

what he had been doing, he said very little. Only their mother told them what

they wanted to know about oil underground and the dividend checks the family

received every year.

*

One winter night, their father came home early. His left

hand was wrapped in bandages like a fat white mitten. There had been an

accident; his hand was smashed. After a couple of days, they removed the

bandages to take pictures, pictures Isabel can still draw up in her mind:

horizontal blue lines where fingernails should have been; swollen, flat,

crooked fingers that all curved in the same direction at the middle joint.

Daddy, why are your fingers going west? Isabel asked.

Having just learned how to use a compass, she believed left was always

west.

There was no answer. He thought he would never play

guitar again.

Years later, in Portland,

their father began to tell them his stories. They trickled out of him, as if

his past were slowly melting: the early days of long winters snowed in at the

homestead; his father shooting the first moose to wander down the driveway in

the fall; moose sandwiches for months; working summers as a teenager, cleaning

trash and outhouses in camp grounds (banging a big aluminum spoon against the

garbage pails to frighten off bears); leaving home at sixteen to play music

with feckless friends; his father getting their band a gig at a bar (brothel)

in Kenai, not asking how his father knew the owner (madam); searching piles of

fish heads for a human hand at the cannery one summer; the fishing boat he sank

all his money into; the friend who sank the boat; and, eventually, working on

the North Slope.

There were only two places to work, he said: the

canneries or the Slope. He had worked both. It was an explanation and an

apology. Though for what, Isabel still wasn’t sure. He always seemed to be

flying away from them when they were little girls. Isabel thought that he believed

this was the reason their mother stopped loving him. That was an easy

explanation, but the apology was more complicated.

There was the pipeline and the oil that thrummed through

it. There was evidence of harm all around—as close as the end of his arm.

Beyond, there was the spill that coated the sea and the coastline and all the

animals. Then there was the thaw, the threateningly deep, vast thaw: a lucid

dream of a legacy for children who know better but cannot stop it.

Isabel cannot read magazine articles or books about the

North. She cannot watch the nature programs about the migrations of birds and

mammals dwindling, the sea ice thinning, and the erosion of islands. And she

does not want to know what has happened to her great-grandmother’s house by the

woods, sold years ago to people who let gutted cars rot in the front yard.

When she thinks about her northern childhood now, she

thinks of her father, flying to the Slope with all the other fathers, toiling

in permafrost. She sees him in his work coat and heavy boots, hardhat over a

woolen skullcap, slipping coins into the slot of a vending machine, pressing

the button and hearing the clink and the drop, reaching his undamaged left hand

through the metal flap for the candy bar.

© 2012 Alexis M. Smith

Wednesday, October 3, 2012

Swimming Away: The Chronology of Water by Lidia Yuknavitch

The Chronology of Water

by Lidia Yuknavitch

Hawthorne Books

Guest Review by Sara Habein

I had a dream about this review. Not the actual writing of it ¾ watching myself with a notebook or laptop would be too dull to note ¾ but rather the thematic turmoil involved. I stood against the front door at a house party while three men in their early 20s tried to gain entry. They yelled through the window that there was no point in fighting. They would find a way inside. The party had stopped ¾ we had been playing records and dancing ¾ as the women in the house scrambled to keep them out. I awoke before either group could claim victory. I don’t know what exactly would have had happened had the men reached us, but I do know that they believed that in whatever it was, it was their right. “Getting away” with misbehavior didn’t enter into it; they decided to take what was “theirs.”

I awoke thinking of Lidia Yuknavitch's memoir The Chronology of Water and how she couldn’t protect herself by staying inside the house. She had to swim away.

Sometimes I think my voice arrived on paper. I had a journal I hid under my bed. I didn’t know what a journal was. It was just a red notebook that I wrote pictures and true things and lies in. Interchangeably. It made me feel like someone else. I wrote about my father’s angry loud voice. How I hated it. How I wished I could kill it. I wrote about swimming. How I loved it. About how girls made my skin hot. About boys and how being around them made my head hurt. About radio songs and movies and my best friends Christy and how I was jealous of Katie but also wanted to lick her and how much I loved my swim coach Ron Koch.

I wrote about my mother…the back of her head driving me to and from swim practice. Her limp and leg. Her hair. How gone she was, selling houses, winning awards into the night. I wrote letters to my gone away sister that I never sent.

And I wrote a little girl dream. I wanted to go to the Olympics, like my teammates.

It is interesting how our own experiences become what we perceive as “normal,” and that deviations from that are an anomaly. In elementary school, I was familiar with an “angry loud voice,” but when we learned about physical and sexual abuse, my young mind thought, “Well, that’s horrible, but don’t people know that? Who would do that to another person, on purpose? Who thinks that’s okay, except the very, very bad?”

How much I didn’t understand where the danger lived.

The slap of a father’s hand against my friend’s fourteen-year-old head.

The distant cousins whose abuse we’d gone so long without knowing.

The sobs of a nineteen-year-old friend whose mother has finally admitted that her father used to touch her and her sister.

The confessions of so many who Did Not Report.

Spouses, parents, relatives, boyfriends, girlfriends, supposed “friends.” The stories are not new, but they are numerous. Gut-punchingly numerous.

Lidia Yuknavitch grew up with a distant, alcoholic mother and a father who beat and molested her and her sister. What she had was the water. Beginning in Washington state, then moving to Florida, she would swim competitively all through her childhood, all the way until the college scholarship offers started arriving. “Did I think I was special?” Again and again, her father informed her that she would not be leaving for these “snob” schools. When a letter arrived from Lubbock, Texas, her father was at work. Her mother signed the paperwork. With a big black suitcase, Lidia swam away.

When I say we partied, I mean an epic poem.

[....]

I lost my scholarship the second year. I flunked out the third.

Still, this isn’t a story only about abuse or about addiction. It isn’t even necessarily about fleeing one family for another. Yuknavitch writes about how she learned to carry herself, to not feel shame over surviving in her own way. She finds her power in her sexuality ¾ her own, not the domain of anyone else ¾ and in her body. A body can be a miracle, but a body is like the rest of life, with birth and death all wrapped up into one.

The book opens with the stillborn arrival of her daughter. “Events don’t have cause and effect relationships the way you wish they did,” she writes. “It’s all a series of fragments and repetitions and pattern formations. Language and water have this in common.”

The birth-death of her daughter is a nasty, debilitating wound that takes years from which to marginally recover. I don’t know that anyone ever fully recovers from the death of a child. One just learns to live with the ache.

Yuknavitch returns to school though, this time in Oregon, and even stumbles into writing a book with Ken Kesey and twelve graduate students. She is not a grad student yet, but Kesey, having lost his son and knowing her story, has her stay. If every Oregon writer within a certain time frame has a Ken Kesey story, fine, but that didn’t make Yuknavitch’s experience any less valuable. It is in this environment, among these artists and writers, that she begins to heal. At one point, she listens to a lecture by an unnamed “big-time academic” and photographer. She melts at the sight of the woman. She needs to know her, to shake her hand.

I saw stars as I let go. Her hair smelled like rain.

I remember leaving the campus feeling like I was exactly like anyone.

But it would not be the last time I touched her.

I didn’t know yet that desire comes and goes whenever it wants.

I didn’t know yet that sexuality is an entire continent.

I didn’t know yet how many times a person can be born.

The woman holds a place in her heart for a long time, but lovers (and husbands) come and go while Yuknavitch figures out how she would like to live her life and how she might find happiness. “I’m just saying healing looks different on women like me.”

I have already given away much of the book, though the fluid nature of the narrative does not mean I’ve spoiled anything. The thought that most often occurred to me while reading was that The Chronology of Water is perhaps the truest thing I’ve ever read. Even if I have not personally experienced the same things, I know many who have, and in the parts where Yuknavitch and I overlap, her words feel so true that they hurt in the same way a massaged, sore muscle does. I wince for a moment, then think, Please keep going. And within all the turmoil, I find a certain amount of peace.

We become our environments. People raised in violence believe violence to be normal until realizing otherwise. People raised with lots of money confuse luxury with personal necessity. A culture that tells women who are raped that they somehow brought it upon themselves produces men and women who punish the victim and not the perpetrator.

Yet, art begets art. Love begets love. Hope begets hope.

Whatever it was or not, there were words. Not just my own. I wrote stories. I wrote books, but the more I wrote the more I saw a door opening behind me, and I saw that if I jammed my motherfucking foot in it, more of us could get through. And that we could make things. Together. What we could make was art. How that mattered.

[....]

Because I believe in art the way other people believe in god.

I know I will read The Chronology of Water again. Its honesty and strength is sustaining, and it is a reminder that healing comes from our own hands. Every bit of hype you may have heard about this book is true. Cheryl Strayed has called it a “brutal beauty bomb” and I couldn’t agree more. Let yourself be enamored, encompassed and engrossed by Lidia Yuknavitch’s words. Now, tell me what you know.

Sara Habein is the author of Infinite Disposable, a collection of microfiction, and her work has appeared on The Rumpus and Persephone Magazine, among others. Her book reviews and other commentary appear at Glorified Love Letters, and she is the editor of Electric CityCreative.

Tuesday, October 2, 2012

Fobbit Tour: Barnes & Noble in Edina, MN

This is the One With All the Friends.

Looking out into audience who came for the Fobbit reading at the Barnes and Noble in Edina, Minnesota, I spotted two e-friends I'd known for years but was meeting in person for the first time. And then there were Joe and Pam, real-life friends I hadn't seen in 25 years (but who had been e-friends for years in the interim). While I appreciate each and every person who comes to the readings on this tour, there's a special frisson of delight that fizzes through the veins when you have these unexpected personal connections along the way. So, it was great to see Joe and Pam, and Cindy and her husband Mark and their son Bee, and novelist Peter Geye who made the special trip to Edina on the night before his own novel, The Lighthouse Road, is officially released. (Peter writes about chilly northern winters, Norwegian immigrants, lumberjacks, a boy named Odd, and ship-building. Do yourself a favor: GO GET IT.) Thanks to everyone for coming out to support me!

|

| Look at all those pens! B&N made sure I didn't run out of ink. |

This is the One With the Tribute to Catch-22.

I began the reading by saying, "Welcome to Banned Books Week." Shortly before I walked over to the Barnes and Noble from my hotel next door, I realized we were at the start of the annual observance of books which have been banned and/or challenged by that small, pale race of creatures known as Those Who Are Afraid of Words. The motto for this week is: "Freadom: Celebrate the Right to Read." Some of our best books have been the victims of the Squelchers--books like The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie, To Kill a Mockingbird, and Where the Wild Things Are by Maurice Sendak. Of course, one of my favorite "subversive" novels is Catch-22 by Joseph Heller. So, as soon as I arrived at the bookstore, I hunted down a copy of the book and then opened tonight's Fobbit event by reading the first paragraph of Chapter 19:

Colonel Cathcart was a slick, successful, slipshod, unhappy man of thirty-six who lumbered when he walked and wanted to be a general. He was dashing and dejected, poised and chagrined. He was complacent and insecure, daring in the administrative stratagems he employed to bring himself to the attention of his superiors and craven in his concern that his schemes might all backfire. He was handsome and unattractive, a swashbuckling, beefy, conceited man who was putting on fat and was tormented chronically by prolonged seizures of apprehension. Colonel Cathcart was conceited because he was a full colonel with a combat command at the age of only thirty-six; and Colonel Cathcart was dejected because although he was already thirty-six he was still only a full colonel.Now I ask you, why would anyone want to smother such delicious writing as that?

This is the One With the Banner.

I won't lie: there is something undeniably ego-stroking about seeing your name, face and book cover stretched across the railing above the store's escalators. It's not quite a billboard in Times Square (See Also: Jeffrey Eugenides' Vest), but it's very flattering and red carpet-y for this debut novelist from a small town in Montana. Lin Salisbury and the staff at the Edina B&N went out of their way to make me feel welcome--from the stacks of Fobbits pyramided at the front entrance to the "Attention Barnes and Noble shoppers..." intercom announcements just prior to the reading.

|

| I know what my wife is thinking: "I should have been there to iron his shirt." Me: "I should have worn a vest." |

This is the One With the Pre-Event Jitters Soothed by the Washington Post's Thumbs-Up Review.

It always seems to happen just before I head out the door to a reading/signing: a Google News Alert pops into my inbox, telling me a new review of Fobbit has just been posted to the web somewhere. When I see the email, I tell myself I shouldn't open it, I shouldn't read it just before I step behind the microphone and face another audience, I shouldn't risk the possibility of it being a bad or mixed review which could momentarily derail my mood. (Yes, I'm one of those writers who reads all his reviews, both good and not-so-good; and no, I don't plan to stop...at least not until it gets really bad and unbearable.) I was nervous when I clicked the link for the Washington Post review, fearing the worst. (Yes, I'm a bar-set-low kind of guy who's always listening for the thud of the second shoe to drop.) What a relief, then, to find the Nation's Newspaper liked the book:

Though absurd, these Dickensian characters are all so skillfully wrought that we quickly accept their idiosyncrasies. The language alternates between comic ranting and serious description, especially in the division between Gooding’s inner voice and that of his diary, which contains some of the novel’s most undisguised personal fieldnotes from the author. We know Abrams is speaking to us when Gooding writes, “This time, Don Quixote is in my hands. I’m in the midst of highlighting a passage with a neon-yellow pen — Fictional tales are better and more enjoyable the nearer they approach the truth or the semblance of the truth.”Click here to read the full review

What’s most intriguing about this work is that, at its center, it is both a clever study in anxiety and an unsettling expose of how the military tells its truths. “Fobbit” traces how “the Army story” is crafted, the dead washed of their blood, words scrutinized, and success applied to disasters. “The Fobbits, watching from their sterile distance, struggled to make sense of it,” Abrams writes. “They tried to separate truth from fiction, rumor from confirmed reports.”

Trailer Park Tuesday: Safe as Houses by Marie-Helene Bertino

Welcome to Trailer Park Tuesday, a showcase of new book trailers and, in a few cases, previews of book-related movies. Unless their last name is Grisham or King, authors will probably never see their trailers on the big screen at the local cineplex. And that's a shame because a lot of hard work goes into producing these short marriages between book and video. So, if you like what you see, please spread the word and help these videos go viral.

The book trailer for Marie-Helene Bertino's collection of short stories, Safe as Houses, is as fresh as clean bedsheets, bread just pulled from the oven, and mountain water springing from a glacier. In the space of two-and-a-half minutes, the video manages tell us everything we need to know about the short stories while telling us nothing concrete about their plots. Summarizing short fiction in an equally short trailer can be a challenge--how do you describe a dozen different plots in rapid succession? In the case of Safe as Houses, you don't. It's too big a task to encapsulate stories which are already compressed to something as small, tight and hard as diamonds. So, you give the viewers a sense of what's in store for them between the covers. In this case, that means a disparate parade of video clips: an interview with Bob Dylan, a cartoon, a shot of a stadium being demolished, infomercials, silent films, footage of some nuns dancing around pillars, and--well, you get the idea. This is a delicious stew of images that goes to work on the undercarriage of your consciousness so that you walk away knowing everything and nothing about the book. I haven't read the collection, so I'm not sure how literally they relate to the stories. But it doesn't matter because that's not the point. The idea of a book trailer is to intrigue, to hook, to make us sit up from our bored slouch and say, "WTF?!!" In that case, Safe as Houses is fresh as eggs.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)