Mr. Walpole, for as much as I know him by now, would appreciate grandiosity, mottled with pomposity. And, by the way, when I say “met Hugh Walpole,” I am strictly speaking in the biblio sense of the word. The dude’s been dead for 69 years.

I discovered him on a bookshelf, dirty with neglect, in the garage of a modest house in the foothills of Butte, Montana. My wife and I, always the intrepid antique-hunters, had gone there for an estate sale advertised in the local paper. We found the usual assortment of eight-track tapes, corroded hand tools, macramé potholders, and photo albums featuring children beaming at us from the yellow-tinted 70s. The usual ho-hum junk for a dime.

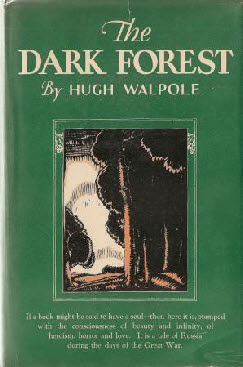

Then I stepped into the garage, saw the bookcase in the corner and those two rows of tattered-but-proud spines. I stepped a little closer and saw that nearly every title was written by the same man: Sir Hugh Walpole.

Hugh who?

His name rang a bell in my head. But only faintly. I was familiar with Hugh Walpole in the same way I was familiar with mascarpone cheese: heard of it, never tried it.

I started pulling the volumes off the shelf and flipping the liver-spotted pages. Above the Dark Tumult

The man running the estate sale—mid-sixties, rumpled clothes, stained teeth—walked over and asked, “You interested in them books?”

I tried to un-widen my eyes. As a book collector in the advanced stages of delirium, it’s best not to play your hand too early. “Oh,” I coughed, “I might take a look at one or two of them.”

“Well, if you want ’em, I’ll give ’em to you for 50 cents each.”

Holy Mother of Book-Glue! My veins constricted and my ear lobes started to tingle.

Five minutes later, I was toting a box brimming with Walpole out to my car. I was moving at a half-trot, hoping I could get in, start the car, and drive away before the poor man realized he’d just been robbed of what looked like genuine literary gems.

At the time, I thought I’d snagged Walpole’s entire canon. Even then I knew he was an author who had languished into obscurity and if I, compulsive reader that I am, had never heard of his works, then surely he couldn’t have written much more than I had in the box sloshing around in the back seat.

Wrong-o, buck-o!

A Wiki-search soon revealed that Sir Hugh Walpole had once been a word factory--his pumping pistons and chugging levers going 24/7 for several decades in the early 20th century. Starting with The Wooden Horse  in 1909 and continuing until his death of a heart attack in 1941 he wrote with the kind of ambition only someone destined for literary glory could sustain. By all accounts, he strained too hard for that glory, eventually earning dismissal by the critics and a withering caricature by Somerset Maugham in his novel Cakes and Ale

in 1909 and continuing until his death of a heart attack in 1941 he wrote with the kind of ambition only someone destined for literary glory could sustain. By all accounts, he strained too hard for that glory, eventually earning dismissal by the critics and a withering caricature by Somerset Maugham in his novel Cakes and Ale . Walpole’s obituary in The Times gave him the kind of back-handed slap no writer deserves: “He had a versatile imagination; he could tell a workmanlike story in good workmanlike English; and he was a man of immense industry, conscientious and painstaking.”

. Walpole’s obituary in The Times gave him the kind of back-handed slap no writer deserves: “He had a versatile imagination; he could tell a workmanlike story in good workmanlike English; and he was a man of immense industry, conscientious and painstaking.”

“Immense industry,” indeed: over the span of a three-decade career, he wrote 36 novels, five volumes of short stories, two plays and three volumes of memoirs. Not to mention the screenplay adaptation of one of my favorite Charles Dickens movies, the 1935 version of David Copperfield

So what happened, Hugh? Where did it all go wrong? Was your fiction really so third-rate that you so quickly tumbled off the literary radar, forever muted to the obscurity of garage sales, flea markets and estate sales? As at least one blogger has noted: “His career stands as a salutary reminder of the fragility of literary reputation.”

Nonetheless, at one point someone must have liked him enough to buy each new release when it hit the bookstore in Butte, Montana. And not just “bought,” but “read.” Even as I left the estate sale, I felt certain that whoever once lived there had devoured each and every one of those Walpoles. I think of her—for I really suspect it was a woman of leisure—absorbed in these novels while outside her window the hills of Butte, Swiss-cheesed with mines, belched toxic smoke. Inside, she lounged in her parlor, Debussy on the Victrola, and let herself be carried away to England’s Lake District on flowery clouds of Walpole's words.

The thin papery sky of the early autumn afternoon was torn, and the eye of the sun, pale but piercing, looked through and down. The eye’s gaze travelled on a shaft of light to the very centre of the town. A little scornful, very arrogant, it surveyed the scene.

--The Inquisitor (1935)

As I do with every book that comes into my library, I opened each of the Walpoles and read the first few paragraphs, knowing that this might very well be all I ever read of the book (sadly, my rate of book intake far exceeds my rate of reading). From the first word, I found Walpole to be a lively, engaging writer who pulled me into his books with both hands grasping my shoulders:

No one perhaps in the United Kingdom was quite so frightened as was Nathalie Swan on the third day of November, 1924, sitting in a third-class carriage about quarter to five of a cold, windy, darkening afternoon. Her train was drawing her into Paddington Station, and how she wished that she were dead!

--Hans Frost(1929)

Miss Henrietta Maxwell, when she was about thirty-five years of age, suffered suddenly from misfortune. She had been for many years quite alone in the world, an only child whose parents had been killed in a carriage accident when she was ten years of age. Then she had acquired an almost masculine independence and self-reliance. Until lately things had gone well with her. Without being rich, she had had, until that fatal August of 1914, quite enough to live upon. She had taken a house in St. Johns’ Wood, not far from Lord’s, with an adorable garden, paneled dining room, and a long music room at that back. She had soon loved this house so much, so deeply, that she had bought it. Then, when the war came, she threw herself completely into war work, nursed in France, worked with desperate seriousness and the severity of a brigadier general over those whom she commanded. Towards the end of 1917 she broke down, had insomnia, came back to England to rest, found it a much longer business than she had expected, and was not really her old self again until after the Armistice. Perhaps she would never be her old self again. Before the war she had not known what nerves were. Now she knew very well.

--“Chinese Horses,” from The Silver Thorn(1928)

And this, perhaps my favorite among the first-paragraphs I read:

Death leapt upon the Rev. Charles Cardinal, Rector of St. Dreots in South Glebeshire, at the moment that he bent down towards the second long drawer of his washhand-stand; he bent down to find a clean collar. It is in its way a symbol of his whole life, that death claimed him before he could find one.

At one moment his mind was intent upon his collar; at the next he was stricken with a wild surmise, a terror that even at that instant he would persuade himself was exaggerated. He saw before his clouding eyes a black pit. A strong hand striking him in the middle of his back flung him contemptuously forward into it; a gasping cry of protest and all was over. Had time been permitted him he would have stretched out a hand towards the shabby black box that, true to all miserly convention, occupied the space beneath his bed. Time was not allowed him. He might take with him into the darkness neither money nor clean clothing.

--The Captives(1920)

In all honesty, there are some clues which point to Walpole’s fall from fame: he is too in love with the comma; subordinate clauses swell the sentences; and he never turned away an adjective begging to be written.

In all honesty, there are some clues which point to Walpole’s fall from fame: he is too in love with the comma; subordinate clauses swell the sentences; and he never turned away an adjective begging to be written.But yet, there is something about his writing which draws me in, makes me want to read more, despite the obvious flaws bogging down the pages.

Leafing further into The Silver Thorn, I come across a couple of passages from two short stories which tickle the bibliophile in me:

“What a jolly lot of books you have!” Foster turned round and looked at Fenwick with eager, gratified eyes. “Every book here is interesting! I like your arrangement of them too, and those open bookshelves—it always seems to me a shame to shut up books behind glass!”

--“The Tarn”

In [Miss Maxwell’s] heart of hearts she thought that nobody’s books looked quite so perfect in their shelves as did hers. They seemed to like the room that they were in. They wanted to show her that they did, and there was so much sun in that library that their hearts were thoroughly warm, and some of the most cynical books in the world became quite amiable and kindly from living in that particular corner of that library. In fact, after reading Stendhal one winter very seriously, she moved him bag and baggage from the rather chilly corner by the door and put him in the sun-drenched spot near the window and hoped it would do him good.

--“Chinese Horses”

Well, I’m sorry to report that, due to the location of the Ws in my own library, Mr. Walpole’s books will have to lodge in the passageway just outside my main library in the basement. It’s a dark and sometimes chilly location, but I hope that the warmth of Walpole’s sentences will brighten the gloom of Virginia Woolf, Richard Yates, and Emile Zola.

I could be entirely mistaken about the perceived charms of Walpole’s writing. After I start reading his novels, he may turn out to be like that cool guy you meet at the party who seems full of wit and outrageous exploits, but who—after you get to know him and have heard him drone through the same stories for the fourth time—turns out to be nothing more than a pompous blowhard. If that’s the case, Mr. Walpole, you deserve your cold, dark shelf in the basement. Otherwise, I'm glad to have made your acquaintance.

So how did it turn out? Did he wear thin? I read Walpole's Rogue Herries (sp?) a few years ago and thought it had some real power to it. As a novelist (and, now, the publisher of a rather odd-ball, throwback sort of magazine) who tends toward involved syntax and an old-fashioned sensibility [www.moosepath.com], I may be on a sympathetic wave-length. But an eccentrically constructed novel it was! I've always meant to return to him. I enjoyed this post and will look forward to reading more of your online literary journal.

ReplyDeleteBest wishes,

Van

Van,

ReplyDeleteI'm sorry to report that I *still* haven't cracked open any of Walpole's books. He's on my list of Books-To-Read, but other (more modern) novels have trumped him and pushed him farther down the list. Thanks for giving us a report on the Walpole you read. It gives me hope there might be some good stuff waiting for me when I eventually get around to him.

Interesting about this Hugh Walpole, isn't it? At the age of 12 or 13 I read his Fortitude, and parts of it stuck with me all of my life - I am now 70! Ordered an old copy of it when I was about 55 and re-read it, and still enjoyed it and understood why it was important to me - the title said it all. When I discovered C.G. Jung found some of his novels psychologically interesting and mentioned one especially. I ordered 2 more of his books and enjoyed them. Jung arranged to meet him, I believe, but Walpole showed no interest in making his acquaintance. Recently visiting an Inn in VA I just knew I would find an old Walpole novel there and walked right to the place where one was nestled waiting for me! It has been a quick read and caused me to see what others know or might say about his books! Lots of words, but good descriptions and depth of emotions expressed.

ReplyDeleteKim,

ReplyDeleteThanks for reminding me I *STILL* need to take Mr. Walpole down off my shelf and read him. Perhaps a good place to start is "Fortitude," a novel whose opening lines are "'Tisn't life that matters! 'Tis the courage you bring to it." I can see why that book in particular has stuck with you down through the years. And I love thinking about how Mr. Walpole was sitting there in that Virginia inn all those decades, waiting for you to come along. It isn't us who look for books, it's the books who search for us.

Marvelous post! I've read a few Walpoles, the most recent "The Joyful Delaneys" just last week. He's surprisingly good! I'm keen to track down more - I do envy you your find. You *should* read him!

ReplyDeleteI've just linked your post on my own blog - too good not to share.

I have read Walpole and I have been fascinated by the descriptions of nature and by the acute analysis of characters.Many of his remarks are very for his time I think that enforces the long tradition ob english novel

ReplyDeleteI encountered Walpole's name in a Hemingway short story, "The Three Day Blow."

ReplyDeleteIt was paired (or compared) with Chesterton, of whom I am a great admirer. So it struck a chord, and I asked myself, "who is this man, that he may compared to such a literary titan?"

Well, Hemingway was the judge, and had deemed them both significant. So I decided, rather arrogantly, that it was enough of a recommendation, and I started to comb the internet.

I am disturbed by the ripple Walpole cast, perhaps because he sought out smaller pools. I bought his novel The Sea Tower on impulse, knowing nothing of its content save what I could determine from its title.

I received an old, first-edition hard cover (which had become rather soft) in the mail several days later. Yellowed pages, frayed at the ends, revealed a neat and even type that would soon, as you said, pull me into his books "with both hands grasping my shoulders." I was rapt.

Please consider this as a recommendation from a fellow literary pilgrim. Though it may mean little, Walpole's works were filled with heart and clarity, and I have enjoyed them greatly.

A little late to the discussion, but I am in the middle of Hans Frost. I've this nice Grosset & Dunlop edition with dust jacket sitting on my shelf for quite a while. Got to Walpole through Maugham. I'll decide if Maugham did him a bad turn or a horrific turn when I finish.

ReplyDeleteI am delighted to have stumbled upon your blog this evening as I have been a collector of Hugh Walpole books since finding one, yes, at a garage sale. Imagine the surprise to find that I would not be alone at a fan club meeting. Even my husband rolls his eyes and would gladly toss them, I suspect he is in the Maugham camp. I do hope that you will have a rainy day, a pot of tea and another unread Walpole in your near future.

ReplyDeleteI first encountered Walpole via his children's books, Jeremy and Jeremy and Hamlet, both of which are set in Polchester. They belonged to my mother and she had kept them. In my late twenties-early 30s, I discovered more of his books in the University of Arizona library. I now have a sizable collection of his books. Particularly love The Cathedral, The Inquisitor, Wintersmoon, Harmer John, The Sea Tower, and The Blind Man's House.

ReplyDeleteI discovered Hugh Walpole on the shelves of a charity shop 10 years ago back in 2011. I could have never have know what a collecting journey it would take me on. I now run https://hughwalpole.com and have every work (including his plays, privately published books, and one of his sketchbooks) which I am now writing about at the site. Nice to see others still appreciating his work!

ReplyDelete