1. Is writing hard work? Richard Ford responds in The Guardian:

I've always had uneasy loyalties about the relevance of the term "work" to the activities I perform every day, and which occupy the hours when most other people are in fact "working." I write novels and stories and essays for a living. And while I fairly mindlessly refer to what I do as "work" ("I'm working, I can't help you shovel the driveway;" "I start work every day at eight and work on 'til cocktail hour;" "I've been working way too hard, I need a trip to Belize"), it's hard for me to think that work is what I really do. Work, after all – to me, anyway – signifies something hard. And while writing novels can be (I love this word) challenging (it can also be tedious in the extreme; take forever to finish; demoralise me into granite and make me want to quit and find another line of work), it's not ever what I'd call hard.Speaking of Richard Ford and "hard work," be sure to check out the latest anthology he edited: Blue Collar, White Collar, No Collar.

2. Flannery O'Connor certainly knew the meaning of hard work. Even after she was stricken with lupus, she knuckled her way through a daily regimen of writing, energy rarely flagging, mind fiercely alive at the typewriter. She left us some of the brightest bonfires of 20th-century fiction, but she was also a prodigious letter-writer. This Recording celebrates some of those epistles, remarking "Everything is in the letters of Flannery O'Connor. Everything." As a writer struggling with the commercial viability of my own novel,* I heard a loud choir of little word-scribblers start cheering inside my chest when I read this letter O'Connor wrote to Paul Engle, director of the Iowa Writers' Workshop, in 1949:

When I was in New York in September, my agent and I asked [John Selby, an editor at Rinehart] how much of the novel they wanted to see before we asked for a contract and an advance. The answer was--about six chapters. So in February I sent them nine chapters (108 pages and all I've done) and my agent asked for an advance and for their editorial opinion.I love her absolute belief in her own work and her steadfast refusal to compromise. That is what makes Flannery Flannery. The novel in question is, of course, Wise Blood

Their editorial opinion was a long time in coming because obviously they didn't think much of the 108 pages and didn't know what to say. When it did come, it was very vague and I thought totally missed the point of what kind of a novel I am writing. My impression was that they want a conventional novel. However, rather than trust my own judgment entirely I showed the letter to [poet Robert Lowell] who had already read the 108 pages. He too thought that the faults Rineheart had mentioned were not the faults of the novel (some of which he had previously pointed out to me). I tell you this to let you know I am not, as Selby implied to me, working in a vacuum.

In answer to the editorial opinion, I wrote Selby that I would have to work on the novel without direction from Rinehart, that I was amenable to criticism but only within the sphere of what I was trying to do.

In New York, a few weeks later, I learned indirectly that nobody at Rinehart liked the 108 pages but [William Raney, another Rinehart editor] (and whether he likes it or not I couldn't really say), that the ladies there particularly had thought it unpleasant (which pleased me). I told Selby that I was willing enough to listen to Rinehart criticism but that if it didn't suit me, I would disregard it. That is the impasse.

Any summary I might try to write for the rest of the novel would be worthless and I don't choose to waste my time at it. I don't write that way. I can't write much more without money and they won't give me any money because they can't see what the finished book will be. That is Part Two of the impasse.

To develop at all as a writer I have to develop in my own way. The 108 pages are very angular and awkward but a great deal of that can be corrected when I have finished the rest of it--and only then. I will not be hurried or directed by Rinehart. I think they are interested in the conventional and I have had no indication that they are very bright.

. It was published on May 15, 1952 and the world of American letters would never be the same again.

. It was published on May 15, 1952 and the world of American letters would never be the same again.3. In other FO'C news: Andalusia, O'Connor's farm in Milledgeville, Georgia, has received a grant for the preservation of the oldest structure on the property, the Hill House, "the home of Jack and Louise Hill, African-American farm workers at Andalusia during the period of O’Connor’s residence."

4. For your daily diversionary delight, I give you Ben Greenman's Museum of Silly Charts. I'm particularly fond of the one which graphs the frequency of letters in Leaves of Grass, The Great Gatsby

and "Bartleby, the Scrivener."

and "Bartleby, the Scrivener."This graph, too, took quite a bit of work, and I was surprised to see that it actually yielded some results. The Great Gatsby has more g’s than f’s, which is uncommon, and may have something to do with West Egg and East Egg.

5. For the "When We Fell in Love" series at Three Guys One Book, Alan Heathcock rhapsodizes on Charlotte's Web:

I felt quite surprised to be crying when reading Charlotte’s Web. I still have the copy of the book from my childhood, its pages yellowed, the back cover torn in half. On the front cover is an illustration of a little girl, a worried looking little pig in her arms, a goose at one elbow, a sheep at the other, a spider dangling above them all. I can only guess what the bark-kneed ten-year old jock version of myself thought of it, this baby book, this silly tale about girls and farm animals. But I found myself deeply taken by the plight of the little pig, a runt named Wilbur. From the moment of his birth, everything was set up against Wilbur, and only by a few fortuitous bounces did he live at all. And even then, author E.B. White did not shy away from the harsh truths of the Wilbur’s world. Pigs were killed. Pigs would become bacon and ham for the farmer’s table. Wilbur would die. The bitter old sheep told Wilbur they were fattening him for slaughter and the spider, a kind soul named Charlotte, assured him it was true.Leave it to Heathcock to turn a sweet, sentimental kid's version of Animal Farm

“I don’t want to die!” screamed Wilbur, throwing himself to the ground.

And I desperately did not want Wilbur to die, and the runt pig inside me threw himself to the ground and screamed, too. It was a profound moment for me, and I cried for Wilbur, not yet knowing I was crying for myself.

The best of what literature can do for us is to allow us to face ourselves, but in a way that’s bearable. Story can strike us at the buried and otherwise impenetrable core of those things which make us afraid, make us ashamed, make us swoon and question, make us imagine, and understand, the world in new ways. My wife is a fifth grade teacher and we’ve talked often about the role of the teacher being that of curator, of knowing the vast spectrum of books and suggesting books to students that might allow them to have this deep and meaningful interaction with the written word. Lifetime readers are generally made by those moments that the best of books can provide, that awakening, deep and visceral, striking our emotions and intellect and imaginations, the interaction of our inner selves with the written word.

into a meaningful cornerstone of his reading life. His tribute to E. B. White's beloved classic might just be the most beautiful thing I've read on the web all week.

into a meaningful cornerstone of his reading life. His tribute to E. B. White's beloved classic might just be the most beautiful thing I've read on the web all week.6. Explaining the Kindle to Charles Dickens: it's "just a lot of books inside a big book."

7. Attention, Jeffrey Eugenides fans: The Millions has the first paragraph of his much-anticipated novel The Marriage Plot

(coming from Farrar, Straus, Giroux in October). Check out that paragraph here.

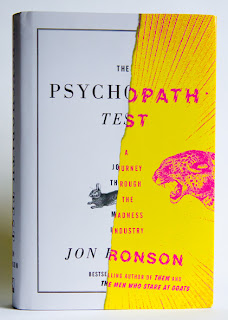

(coming from Farrar, Straus, Giroux in October). Check out that paragraph here.8. Awesome Cover #1:

Designer Matt Dorfman gives a little background at his blog:

Riverhead did not skimp on the production touches for this one. They sprung for a combination gritty matte finish (which covers the white paper portions of the jacket) and a shiny gloss for the yellow/magenta “crazy” half, thereby giving your sense of touch a noticeable edge if you find yourself blindly scanning your shelf for this book in a dark room (which I have done).

9. Awesome Cover #2:

There's something about this cover which is beautiful and sad at the same time; it puts the reader in the right frame of mind to approach the book even before going beneath the cover: contemplative, melancholy and haunted. My only complaint: though credit should go where credit is due, I think the design would have benefited by removing the names of the editors in the lower left corner--leave that part of the black sky blank. By the way, you'll notice this is the 10th Anniversary Issue of Poetry After 9/11

. The anthology was the first book published by Melville House, the unique take-no-prisoners publisher who has done some excellent work in the past decade. Melville House grew out of the blog MobyLives (which I followed like a zealot back when I was a toddler on the Internet). Since then, publisher Dennis Loy Johnson has brought out some great titles--including a line of novellas, reprints by the masters and mistresses of world literature (including Chekhov, Kipling, Wharton, Cervantes, and--of course--Melville). For more on Melville House, check out this interview with Johnson at nthWORD.

. The anthology was the first book published by Melville House, the unique take-no-prisoners publisher who has done some excellent work in the past decade. Melville House grew out of the blog MobyLives (which I followed like a zealot back when I was a toddler on the Internet). Since then, publisher Dennis Loy Johnson has brought out some great titles--including a line of novellas, reprints by the masters and mistresses of world literature (including Chekhov, Kipling, Wharton, Cervantes, and--of course--Melville). For more on Melville House, check out this interview with Johnson at nthWORD.*Try telling a publisher you're writing a funny novel about the Iraq War and see how far you get.

I found that Poetry After 9/11 cover very moving, which is not something I say about a book cover very often. Or ever, maybe.

ReplyDeleteSo glad you highlighted Flannery O'C here. I keep her collection of letters: Habit of Being close at hand. It was from those letters that I witnessed and first learned of her deep faith in her work and her ability to ignore those ladies she frequently offended.

ReplyDeleteThe struggle over "Wise Blood" continued for a while until Flannery was at last able to free herself and the novel from Selby's contact. Flannery wrote of that final event "Selby was able to write the I was 'prematurely arrogant' -- a phrase I supplied him with."

ReplyDelete