As I mentioned earlier,

The New Yorker has released its list of "20 Under 40" promising fiction writers to predictable hue and cry. Since I'm on the far side of 40 and the shy side of 50, I'm trying not to take this as a personal affront (he says, shaking his fist at the Manhattan skyscraper, spitting on the sidewalk, and yelling uselessly up to the 15th Floor, "You haven't heard the last of me yet,

New Yorker!").

I bought the "20 Under 40" issue and spent the better part of a month reading the stories from "writers I should be watching." Excuse me while I stifle a yawn and check to see if my socks are still on (

Yep). The stories aren't bad (in the way a tuna-fish sandwich left out in the sun all afternoon is said to be bad), but they also aren't great (as a Five Guys double-patty cheeseburger with jalapenos and mayo is great--nay,

tongue-curlingly great!). I've seen more electricity at a Luddite Convention.

But

The New Yorker list is beneficial if for nothing else than to spark another of those one-upping debates the lit-blogging community loves so well. "You think '20 Under 40' is so great? Well,

I've got the '10 Over 80' list right here, buddy!" I could fill an entire blog post with nothing but hyperlinks directing you to lists of the over-looked and under-appreciated writers, but here are two of them which have piqued my interest: for the British perspective, check out

The Telegraph's 20 Under 40 list; for the indie-publishing perspective, go to

The Emerging Writers Network's 20 Writers to Watch list (many, many unfamiliar writers on there I need to check out!).

As for my list? Previously, I'd trumpeted 9 under 40, but now I've reconsidered and expanded my choices. Taking the liberty of adding a decade to

The New Yorker list to include my fellow fortysomethings, here are my 20 personal favorites, keeping in mind there are plenty of other very good writers (or so I've heard) whose works I've never read--including Dave Eggers, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and Jonathan Safran Foer.

Here's my list, in no particular order:

Chris Ware

I've read my fair share of graphic novels (though less than I should), and Ware is still the one who touches me deepest. I haven't read Alison Bechdel's

Fun Home

, which has piled up the accolades, but for my money nothing can beat Ware's

Jimmy Corrigan, the Smartest Kid on Earth

for sheer beautiful misery. Published in 2000, one year before our national tragedy, it chronicled the awkward, lonely life of the titular loser who must deal with father issues in the bleak midwinter of his life. Imagine Richard Yates' characters trapped in the panels of a comic strip and you'll have some inkling about the depth of wallow in

Jimmy Corrigan.

Laura van den Berg

I've had my eye on van den Berg for more than two years now, ever since I read the issue of

One Story featuring the title story from her debut collection,

What the World Will Look Like When All the Water Leaves Us

, about a teenage girl accompanying her scientist mother on a trip to Madagascar to study lemurs. I haven't had the chance to read the rest of the stories in this new collection, but the jacket copy at publisher Dzanc Books' website hints at the odd and beautiful ways that van den Berg uses myth and humor to reveal the human condition:

A failed actress takes a job as a Bigfoot impersonator. A botanist seeking a rare flower crosses paths with a group of men hunting the Loch Ness Monster. A disillusioned missionary in Africa grapples with grief and a growing obsession with a creature rumored to live in the forests of the Congo.

C. J. Box

I don't read a lot of contemporary mysteries. I mostly prefer the locked-room puzzles of Agatha Christie, Ellery Queen and Rex Stout. But when I do reach for murder and mayhem, one of the first places I go is Box's Joe Pickett mysteries, books which combine my love for the Rocky Mountain west, and the morbid beauty of blood-spatter on snow. Pickett is a Wyoming game warden whose cases usually revolve around the uneasy intersection between man and nature--elk poachers gone awry, kidnappers retreating from society, etc. He is one of the most interesting "detectives" working in fiction these days. I especially like Box's stories for their depth, complexity, and genuinely-earned emotional pitch.

Click here to read my review of

Nowhere to Run .

Joe Hill

To paraphrase Willie Nelson, the guy can scare the paint off a trailer hitch with his ghost stories. Sure, as the son of horrormeister Stephen King, Hill comes by his talent honestly. But swing a cat in a crowded room and you'll hit plenty of talentless offspring of artists (Drew Barrymore, anyone?). Hill creeps under the skin quietly and unforgettably, especially in the short stories of

20th-Century Ghosts

. Hill makes horror feel as fresh as the day his father published

'Salem's Lot

. In

20th-Century Ghosts, the frights come by way of a haunted movie theater, a museum which collects the "last breath" of famous people and "Pop Art," a sad, bizarre tale of an inflatable boy.

Amanda Eyre Ward

Some bookstores might shelve Ward with the Picoults and Kinsellas and Weiners in the ill-named "Chick Lit" section, but Ward has far broader appeal and, frankly, more smarts than the average writer of "women's fiction." I also love Ward's sure-footed, off-handed way with humor. She excels at the self-deprecating zinger, even in stories about Death Row, post-9/11 terrorism, and miscarriage. Among other things, she knows how to open a short story with unforgettable sentences--as in the one from "Motherhood and Terrorism":

Lola thought the baby shower would be canceled due to the beheading, but she was wrong. I could go on and on about the merits and pleasures of Amanda Eyre Ward, but perhaps you should just read my reviews

here and

here of her books

Sleep Toward Heaven

and

Love Stories in This Town

. If you do nothing else this week, hunt down the latter collection and read her classic story of a masturbator on the loose in the Butte Public Library ("Butte as in Beautiful").

Kevin Brockmeier

With his fabulist tales of spirituality and magical realism, Brockmeier comes close to being our American Gabriel Garcia Marquez. In

my review of

The View from the Seventh Layer

, I wrote:

In his 2006 novel, The Brief History of the Dead , Kevin Brockmeier gave readers a dazzling vision of an afterlife where residents of a city are kept "alive" only as long as someone back on earth remembered them. In his new collection of short stories, Brockmeier again proves to have a boundless imagination when writing about matters of the spirit. He takes readers on a series of magical mystery tours through worlds that only resemble ours on the surface; scratch deeper, and you'll find a place that's a delirious mix of science fiction and religion. It's no accident that some of these stories are labeled "fables."

, Kevin Brockmeier gave readers a dazzling vision of an afterlife where residents of a city are kept "alive" only as long as someone back on earth remembered them. In his new collection of short stories, Brockmeier again proves to have a boundless imagination when writing about matters of the spirit. He takes readers on a series of magical mystery tours through worlds that only resemble ours on the surface; scratch deeper, and you'll find a place that's a delirious mix of science fiction and religion. It's no accident that some of these stories are labeled "fables." Brockmeier's tales are surprising, meaningful, and sentimental in all the right places. I can't wait to read what he writes next.

John Brandon

Brandon's first novel,

Arkansas

, flew under the radar two years ago, and here's hoping his newest one,

Citrus County

, gains elevation and starts showing up as a major blip on reader radars everywhere. Here's what I had to say about Arkansas (in a mini-review at

January Magazine) when it was first released:

Drug-running gangsters are at the heart of Arkansas

, John Brandon’s debut novel from McSweeney’s Books; however, as the title reminds us, the shady business is carried out not in Harlem, Miami or Vegas but the rural Southeast. This allows Brandon to indulge in the kind of quirky writing that distinguishes Southern grit-lit and, true to its McSweeney’s roots, this neo-noir novel is cynical and hip. Kyle Ribb and Swin Ruiz are petty criminals who, for lack of anything better to do, start working for a black-marketeer named Frog in the land of trailer parks and deep-fried breakfasts. The two run packets from an Arkansas state park where they have phony cover jobs as assistant park rangers. Brandon keeps the pace brisk and tense. The violence, when it comes, surfaces quickly, snaps at us in the space of a paragraph, then recedes just as fast.

Kyle Minor

Gritty, unsparing, and wincingly funny, Minor goes places with his stories where you might think twice about setting foot.

Click here to read one of his short stories, "The Truth and All Its Ugly;" then, after you've picked your teeth up off the floor and shoved them back into your bleeding gums, check out his debut collection

In the Devil's Territory

(also from Dzanc Books). Want more encouragement? Here's the first line of the first story in that book:

I hate Christmas, but this year is different because there is a small chance my wife will die and take our unborn child with her.

Rebecca Barry

I totally dug Barry's debut short story collection

Later, at the Bar

. I said it was "inspiring fiction which just happens to be set in a room filled with smoke, sad songs and slurred words." That book came out in 2007. I've been keeping my eyes peeled (

ouch!) for more Barry to hit the bookstores. However, there's been nothing but crickets since then. Ms. Barry, when are you coming back?

Adam Braver

It's a tricky thing to make historical fiction fresh without slopping into the pedantically dull or, on the opposite end of the spectrum, bizarre-for-the-sake-of-bizarre. Braver's first book,

Mr. Lincoln's Wars

made me look at five-dollar bills in a whole new light. The "novel" shone a kleig light on Honest Abe's complex inner life from thirteen different perspectives in as many short stories. The tales of Lincoln were just varied enough to be "fresh" and were technically stunning in their execution. His subsquent books have done the same literary psychoanalysis on Jackie Kennedy and Sarah Bernhardt.

Michael Chabon

Maybe it's unfair to give a literary titan like Chabon a slot on a list filled with under-known and over-looked writers, but the simple fact remains that Chabon is under 50 and he is one of the best damned American writers in that age group. 'Nuff said? I think so. For more of my love for MC's work, you can check out my reviews

here, and

there, and

here again.

Roy Kesey

Dzanc Books strikes again! Three years ago, Kesey's short story collection

All Over

was the first book to roll off their presses. It's been nothing but reams of excellent literature ever since.

I waxed rhapsodic about Kesey's talents for

January Magazine back then. Here's part of what I said:

In these 19 stories, Kesey takes the reader on a tour of post-modern fiction that is at once bizarre and completely familiar. Here you'll meet a man named Martin who thinks he's a guitar string, honeymooners who are threatened by llamas, a homeless couple who initially thrive during a garbage strike, and two girls who build a castle -- complete with crenellated parapets -- out of the ingredients at a Pizza Hut salad bar. His story "Wait," about an airport boarding lounge from Hell, is an out-and-out masterpiece. It's a story that starts out in recognizable territory, then slides into the Twilight Zone, and ends on something out of Ray Bradbury, except bleaker and weirder.

Junot Diaz

I missed the buzz-and-hype for Diaz's award-winning debut collection

Drown

. But I was fully on board when, eleven years later, he delivered unto the world

The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao

. In

my review of the Pulitzer-Prize winning novel for

January Magazine, I wrote:

Meet Oscar de Leon, dubbed “Oscar Wao” by bullies who liken him to the foppish Oscar Wilde. Our Oscar is a fat, virginal Dominican-American teenager who carries a Planet of the Apes

lunchbox to school, spends hours painting his Dungeons and Dragons

miniatures, and who knows “more about the Marvel Universe than Stan Lee.” If Nerd was a country, Oscar would be its undisputed king. Oscar is the kind of kid we would avoid on the subway -- sweaty, mumbles to himself, inevitably invades personal space, probably has bad breath. In Junot Diaz' debut novel, The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao

, however, Oscar is the flame and we are the moths. An earnestly open-hearted protagonist, he draws us to him until we incinerate in the intensity of his character.

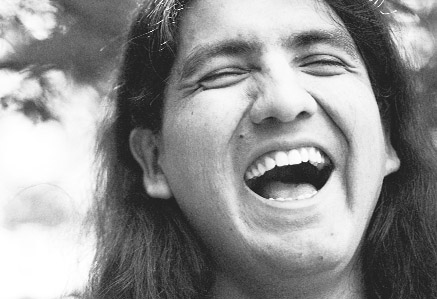

Sherman Alexie

On the page (as well as in person), Sherman Alexie pops and sizzles and does double-cartwheel flips with language. I haven't read everything of his (

Indian Killer

and

Flight

remain untouched), but what I have read, I've really, really liked.

The Lone Ranger and Tonto Fistfight in Heaven

is required reading if you want to know the chemistry for a story fueled by jet-propulsion sentences. But

I also pretty-much liked his other collection

Ten Little Indians

. I once wrote (and still stand by my words):

If there's a bone in Sherman Alexie's body that isn't funny, I'd like to know where it is. The left metatarsal, perhaps; or maybe the coccyx...Take a look at the author photo on the back of his latest book, Ten Little Indians

, and you'll see what I mean. His eyes are squeezed shut and his mouth's wide open in mid-guffaw; the teeth practically leap off the dustjacket. That laughter often leaps right back onto the page. Alexie's sentences are jazzed with jokes, the paragraphs pop with the pleasure of puns.

Jhumpa Lahiri

When I first read Lahiri's collection

Interpreter of Maladies

, it

had as big an impression on my writer's psyche as anything I'd read since Flannery O'Connor. Ten years ago, I wrote in a review that "This is the kind of prose that turns aspiring writers several shades of green in the time it takes them to read one paragraph." Though

that early review of mine slops over the rim of the cup with googly-eyed praise, I still count Lahiri as one of the best stylists around.

Benjamin Percy

Okay, I'm going to be perfectly honest here (as opposed to the imperfect honesty scattered throughout the rest of this blog post): I have not actually read a complete work of fiction by Benjamin Percy. However, I'm including him on this list because: a) I read the first three pages of his forthcoming novel

The Wilding

and the ONLY reason I put it aside was because I'm in the midst of reading two other books and I want to be able to devote my complete attention to the story of three generations of flawed males bonding and breaking in the Oregon wilderness; b) those three pages were pretty fucking good; c) I like elk and Percy's debut collection was called

The Language of Elk

; and d) I've been told by several people whose opinion I trust that I will love Percy. I've been kicking myself from here to Regretsville for not reading

Refresh, Refresh

when it came out a couple of years ago. To put it bluntly, Benjamin Percy is the best writer I haven't read....yet.

Josh Weil

I've raved elsewhere on this site about the excellence of Josh Weil's collection of three novellas,

The New Valley

. If you saw that blog post and haven't yet started reading those three stories about misfits in rural Virginia struggling with loneliness, depression, and turbulent romance...well then, shame on you. Why am I even shouting into the blog-o-sphere if you won't take my advice when I dispense it?

David Foster Wallace

Technically speaking, since he's dead, DFW isn't a "writer to watch," but when I sat and pondered excellence in fiction writing, then got up out of my chair and scanned the 5,000-plus works of fiction on my bookshelf, and then started winnowing the list and narrowing my choices, I couldn't

not include the genius who breathed new breath into the art of the footnote. The first thing I ever read by Wallace was the 1996 "non-fiction" essay "A Supposedly Fun Thing I'll Never Do Again" (then titled "Shipping Out") in

Harper's Magazine. I started choking with laughter and the ONLY reason I'm still here today writing to you is because a co-worker knew the Heimlich maneuver. Later, when I was in the midst of his magnum opus,

Infinite Jest

, more strenuous methods had to be applied in order to bring me back from the dead. I'm still pissed that Wallace hung himself in 2008 when he was 46. He robbed us of his greatness. What remains, however, we must cherish.

Gary Shteyngart

His contribution to the New Yorker's "20 Under 40" issue was easily the best story in those pages. It's an excerpt from his newest novel,

Super Sad True Love Story

, which is a weird and wonderful and hilarious tale of a dystopian future. Based on that story alone, I really need to check out

Absurdistan

and

The Russian Debutante's Handbook. I may need to have the cardiac paddles within easy reach. In

his Washington Post review of

Super Sad True Love Story, Ron Charles writes,

Gary Shteyngart has seen the future, and it has no room for him -- or any of us. His new novel, a slit-your-wrist satire illuminated by the author's absurd wit, follows today's most ominous trend lines past Twitter and Facebook addiction to a post-literate, consumption-crazed America that abhors books, newspapers and even conversation. "In other words," Shteyngart notes, "next Tuesday." This zany Russian immigrant loops the comedy of Woody Allen's "Sleeper" through the grim insights of George Orwell's "1984" to produce a "Super Sad True Love Story" that exposes the moral bankruptcy of our techno-lust. He had me at "slit-your-wrist."

Justin Cronin

Yes, I'm jumping on

The Passage

bandwagon....but what an exhilarating ride that bandwagon is giving! I'm a little more than halfway through the apocalpytic-vampire-child savior novel, but I can tell already it's going to be one of my favorites for this year. Cronin has a beautiful way with horror. Take for instance, these sentences about a vampire attack:

Anthony fell on him swiftly, from above. A scream and then the man was silent in wet pieces on the floor. The beautiful warmth of blood! I'll probably post more about

The Passage after I finish it, but for now let me just close with this unpardonable pun: it's the kind of novel that sinks its teeth into you and never lets go.

So, there you have it: my 20 picks. What are yours? Feel free to post them in the comments section.