Showing posts with label J. D. Salinger. Show all posts

Showing posts with label J. D. Salinger. Show all posts

Sunday, December 20, 2015

A Not-Quite-Definitive Young Adult Reading List

A few days ago, a friend of mine posed a question to me on Twitter: Any good recs for very smart 15 year old girls? I have 2 on my list, and I’m looking for things I don’t know about.

While I’ve read and enjoyed my share of Young Adult literature (starting from the time I was a young adult myself), the genre has really bloomed and boomed in recent years, leaving me a little out of the loop. So, I turned to the Hivemind in my social media circles and asked them for recommendations. To put it mildly, my Facebook account exploded. Golly, you people sure are passionate about your favorite ’tween reads! There were so many terrific (and terrifically diverse) suggestions that I decided to compile them here in one place. You’re welcome.

Before diving into the roster, you should know a few things: this list is far from complete. It begs for additions, which you are free to put in the comments section. Second, I’ve included some books which might not be typical reading fare for teenage girls (I drew the line at including Fifty Shades of Grey, which one Facebook friend suggested--hopefully with tongue firmly planted in cheek). I leave it to the parents and young readers themselves to decide what level of maturity they’re ready for.

I should add that I have only read an embarrassingly small fraction of these, so I can’t vouch for the quality of everything on here. I can tell you, however, that I’ll be using this as a starting point to upgrade my own YA reading.

One last thing: though the original request was for books which would appeal to a teenage girl, I don’t think that should stop any young gentleman from dipping into, and enjoying, this list.

I’ll begin with some personal favorites of my own which didn’t get mentioned by my Facebook users. I have read these and recommend you put them at the top of your reading pile:

Tunnel Vision by Susan Adrian

Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret. by Judy Blume

The Chocolate War by Robert Cormier

I Am the Cheese by Robert Cormier

The Outsiders by S. E. Hinton

Flowers for Algernon by Daniel Keyes

The Catcher in the Rye by J. D. Salinger

Smile by Raina Telgemeier

Sisters by Raina Telgemeier

Drama by Raina Telgemeier

And now on with the rest of the list...

The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie

Never Always Sometimes by Adi Alsaid

How the Garcia Girls Lost Their Accents by Julia Alvarez

In the Time of the Butterflies by Julia Alvarez

Speak by Laurie Halse Anderson

Twisted by Laurie Halse Anderson

Mosquitoland by David Arnold

The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood

Eucalyptus by Murray Bail

The Elegance of the Hedgehog by Muriel Barbery

Shadow and Bone by Leigh Bardugo

The Darkest Part of the Forest by Holly Black

Weetzie Bat by Francesca Lia Block

Tiger Eyes by Judy Blume

Beauty Queens by Libba Bray

Ender’s Game by Orson Scott Card

The Perks of Being a Wallflower by Stephen Chbosky

Girl with a Pearl Earring by Tracy Chevalier

The Hunger Games Trilogy by Suzanne Collins

The Miseducation of Cameron Post by emily m. danforth

Dreamland by Sarah Dessen

Saint Anything by Sarah Dessen

The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Diaz

All the Light We Cannot See by Anthony Doerr

The Nursery Crime series by Jasper Fforde

The Thursday Next series by Jasper Fforde

The Basil and Josephine Stories by F. Scott Fitzgerald

Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close by Jonathan Safran Foer

My Brilliant Career by Miles Franklin

Inkspell by Cornelia Funke

Sophie’s World by Jostein Gaarder

Conviction by Kelly Loy Gilbert

The Fault in Our Stars by John Green

The Unbecoming of Mara Dyer by Michelle Hodkin

Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston

The First Part Last by Angela Johnson

Alice, I Think by Susan Juby

Miss Smithers by Susan Juby

Girl, Interrupted by Susanna Kaysen

I Crawl Through It by A. S. King

The Woman Warrior by Maxine Hong Kingston

The Midwife’s Tale by Gretchen Moran Laskas

This Raging Light by Estelle Laure

To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee

A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L’Engle

Very Far Away from Anywhere Else by Ursula K. Le Guin

The Astrologer’s Daughter by Rebecca Lim

How Green Was My Valley by Richard Llewellyn

The Giver by Lois Lowry

Inexcusable by Chris Lynch

Station Eleven by Emily St. John Mandel

Brown Girl, Brownstones by Paule Marshall

The Rowan by Anne McCaffrey

The Dragonriders of Pern books by Anne McCaffrey

Wildwood by Colin Meloy

Mermaids in Paradise by Lydia Millett

Anne of Green Gables by L. M. Montgomery

The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison

I’ll Give You the Sun by Jandy Nelson

All the Bright Places by Jennifer Niven

Wonder by R. J. Palacio

Sweet Valley High series by Francine Pascal

Jacob Have I Loved by Katherine Paterson

The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath

The Lightning Queen by Laura Resau

Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children by Ransom Riggs

Eleanor & Park by Rainbow Rowell

Fangirl by Rainbow Rowell

Carry On by Rainbow Rowell

Bone Gap by Laura Ruby

Glow by Amy Kathleen Ryan

Franny and Zooey by J. D. Salinger

Challenger Deep by Neal Shusterman

More Happy Than Not by Adam Silvera

Winger by Andrew Smith

A Tree Grows in Brooklyn by Betty Smith

I Capture the Castle by Dodie Smith

The Lies About Truth by Courtney C. Stevens

Nimona by Noelle Stevenson

The Merlin Trilogy by Mary Stewart

The Mysterious Benedict Society by Trenton Lee Stewart

An Ember in the Ashes by Sabaa Tahir

The Joy Luck Club by Amy Tan

Honor Girl by Maggie Thrash

Homecoming by Cynthia Voigt

The Color Purple by Alice Walker

We All Looked Up by Tommy Wallach

This Side of Home by Renee Watson

Code Name Verity by Elizabeth Wein

The Once and Future King by T.H. White

Night by Elie Wiesel

Everything, Everything by Nicola Yoon

The Book Thief by Markus Zusak

And no list of literature for young readers would be complete without mentioning one of my favorite literary periodicals, One Teen Story magazine. A subscription would make a wonderful year-round gift for your favorite young reader.

Labels:

Anthony Doerr,

F. Scott Fitzgerald,

J. D. Salinger

Thursday, November 19, 2015

Amy Gustine’s Library: A Post-Apocalypse Bunker of Books

Reader: Amy Gustine

Location: Toledo, Ohio

Collection Size: 800, give or take

The one book I’d run back into a burning building to rescue: Honestly? My current project, unless I was smart enough to back it up off site. I don’t own any family Bibles, signed first editions, or otherwise irreplaceable books.

Favorite book from childhood: The Trixie Belden mystery series.

Guilty-pleasure book: Dewey by Vicki Myron—nonfiction about a kitten abandoned on a bitterly cold Iowa night in a library’s book drop. Found in the morning nearly dead, Dewey is revived and becomes permanent guardian of the stacks and a community treasure. I’m a sucker for stories about animals who save us from ourselves. I say it’s a “guilty” pleasure because being brought to tears and laughter by a story about a cat seems like something I should feel guilty about—but I don’t.

More than anything else, books vastly expand our world and provide a refuge from it. Since I’m an introvert wary of received wisdom, they were no doubt my inevitable destination, but childhood circumstances probably paved the way. My sister and I split the week between our maternal and paternal grandparents, spent Saturday with Mom and Sunday with Dad. In essence I had six parents in four different neighborhoods. In addition, we attended a small, private school, which meant we had no neighborhood playmates. Because all my homes offered a single TV with three channels, there wasn’t much else to do but read. No matter—a book or two can easily be taken from house to house. Sometimes you find them just lying around. That’s how during grade school I came to work my way through James Michener, James Fenimore Cooper, Edna Ferber, and the first three of V.C. Andrew’s Dollanganger series (forbidden reading, but Grandma was busy making dinner). Prior to that I had been a big Trixie Belden fan (think a younger, more-awkward Nancy Drew). By high school I had found Salinger (Franny and Zooey was my favorite) and the Russians. Crime and Punishment still sits in my all-time top ten.

When I was fourteen my mom let me commandeer a wall of shelves in the guestroom. Then I went off to college, Mom downsized and my books slipped away. I regret losing the marginal comments. The few books I still have from that time are like reading old diaries, but better—they don’t reveal my crushes.

Like my mother, my inner HGTV-snob wants a house ready to photograph on short notice. Like my father, I take comfort in knowing that even post-apocalypse, I would have enough reading material to keep busy for decades. (Yes, I manage to ignore other apocalyptic challenges like food, clean water, and roving bands of cannibals). Fortunately, I have a home office, a living room and family room. The fiction lives in my office arranged alphabetically by author. My current obsession is with the brilliant Dan Chaon.

I also keep story anthologies, literary magazines, books about writing, reference books and research in my office, segregated on their own shelves but otherwise unorganized. Two shelves are dedicated to the to-be-read pile, roughly sorted by novels, story collections, and non-fiction. I’ve got some James Wood up there right now, Thrown by Kerry Howley, and Honor by Elif Shafak, a writer my exchange student from Pakistan turned me onto. When I was writing a novel with a Pakistani character, my research shelves held books on Islam, South Asia, and the Middle East. Now this area holds material for a project I’m not sure I’ll write yet, so I can’t reveal its contents. It might jinx me.

In front of the books sit mementos. The round wooden box was on my grandmother’s screened porch. As a child I always felt boxes with lids were going to have something wonderful and mysterious inside (they never did). Some of the other items are props I’ve used for writing projects, like the car, a replica of one a character owned, and the vase, a piece similar to a jar in my novel about Czech immigrants.

Some of the living room and family room shelves are arranged for looks, in vertical and horizontal stacks interspersed with tchotchkes and photos. There I shelve poetry and nonfiction very roughly arranged by topic and author, but also placed where they look good, or based on size, so the big books are on the bottom of the stack. I have oversized gardening books (lots of pictures) and several coffee-table books on cats (cue Dewey). I also have a set of Harvard Classics my mother gave me (most of which I haven’t read—sorry Cellini, you’re reserved for the apocalypse).

My favorite non-fiction topics are psychology, anthropology, ethics, religion and evolution. My favorite essayist is Alain de Botton. My favorite writer on religion is Karen Armstrong. The single biggest game changer I’ve read as an adult is Guns, Germs, and Steel by Jared Diamond. I would love to see this adapted for young readers and made a standard high school text. (If the job comes available, somebody let me know.)

I borrow books from the library often, but when I read something I love, I allow myself to buy it. Buying a book I’ve already read used to feel indulgent, but I decided it was better than avoiding the library because I’m afraid of finding a book I don’t want to give back. Still, my tendency to feel crushed by clutter requires brutality. I can’t ask myself if I’d like to own a book (the answer is always yes; it’s a book isn’t it?). Instead I ask: Might I read this again, loan it to a friend, browse excerpts for inspiration, or use it to teach a class or write an essay? Because I insist on keeping the fiction alphabetized, when I find no room for a new novel or story collection, I subject nearby hangers-on to this litmus test. Sometimes a handy space opens; sometimes I sigh and start rearranging shelves.

Digital books serve my neat-nick impulse, make browsing annotations easy and assuage my fear of being caught somewhere without something to read, but they have so many failings. My iPad is always tempting me to check email or click over to “breaking news.” I can’t loan digital books to friends. I’m worried Amazon or Apple might take my books away someday. Once in a while, amid numerous in-process books and magazines, I forget that I was reading something digital because the book isn’t lying on my end table...So sad, but true. Also, digital books are just so....unbook-like. It might be asking too much that they smell and feel like real books, but why do they so often lack the same lovely cover art? Why don’t they include the dust jacket copy?

Worst of all, digital books don’t beg to be thumbed through by a bored kid. My office faces the street. One year on Halloween a teenage girl spied my shelves through the window. She commented that she had never seen so many books before. “And shelves...in a house,” she said with evident amazement. It reminded me how lucky some of us are to find James Michener lying next to Grandpa’s chair. As children, we often have only what is within reach inside the four walls of our home. If a book is in reach, the walls somehow both come down and fold protectively around you. That’s the greatest gift my six parents ever gave me.

Amy Gustine is the author of the story collection You Should Pity Us Instead from Sarabande Books (out February 2016). Her fiction has received Pushcart Special Mention and appeared in several publications, including The Chicago Tribune’s Printers Row Journal, The Kenyon Review, Alaska Quarterly Review, North American Review and Black Warrior Review. She lives in Ohio.

My Library is an intimate look at personal book collections. Readers are encouraged to send high-resolution photos of their home libraries or bookshelves, along with a description of particular shelving challenges, quirks in sorting (alphabetically? by color?), number of books in the collection, and particular titles which are in the To-Be-Read pile. Email thequiveringpen@gmail.com for more information.

Labels:

J. D. Salinger,

Leo Tolstoy,

My Library

Thursday, October 16, 2014

Trevor D. Richardson's Library: A Rob Fleming Dilemma

Reader: Trevor D. Richardson

Location: Portland, Oregon

Collection size: 300-ish, plus a lot of comics

The one book I'd run back into a burning building to rescue: Early 20th-century printing of The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, my favorite fictional character

Favorite book from childhood: The Time Machine by H.G. Wells

Guilty pleasure book: I don't really read things that I'm ashamed to admit, but the closest would have to be The Chronicles of Narnia because the religious symbolism is often a little heavy-handed.

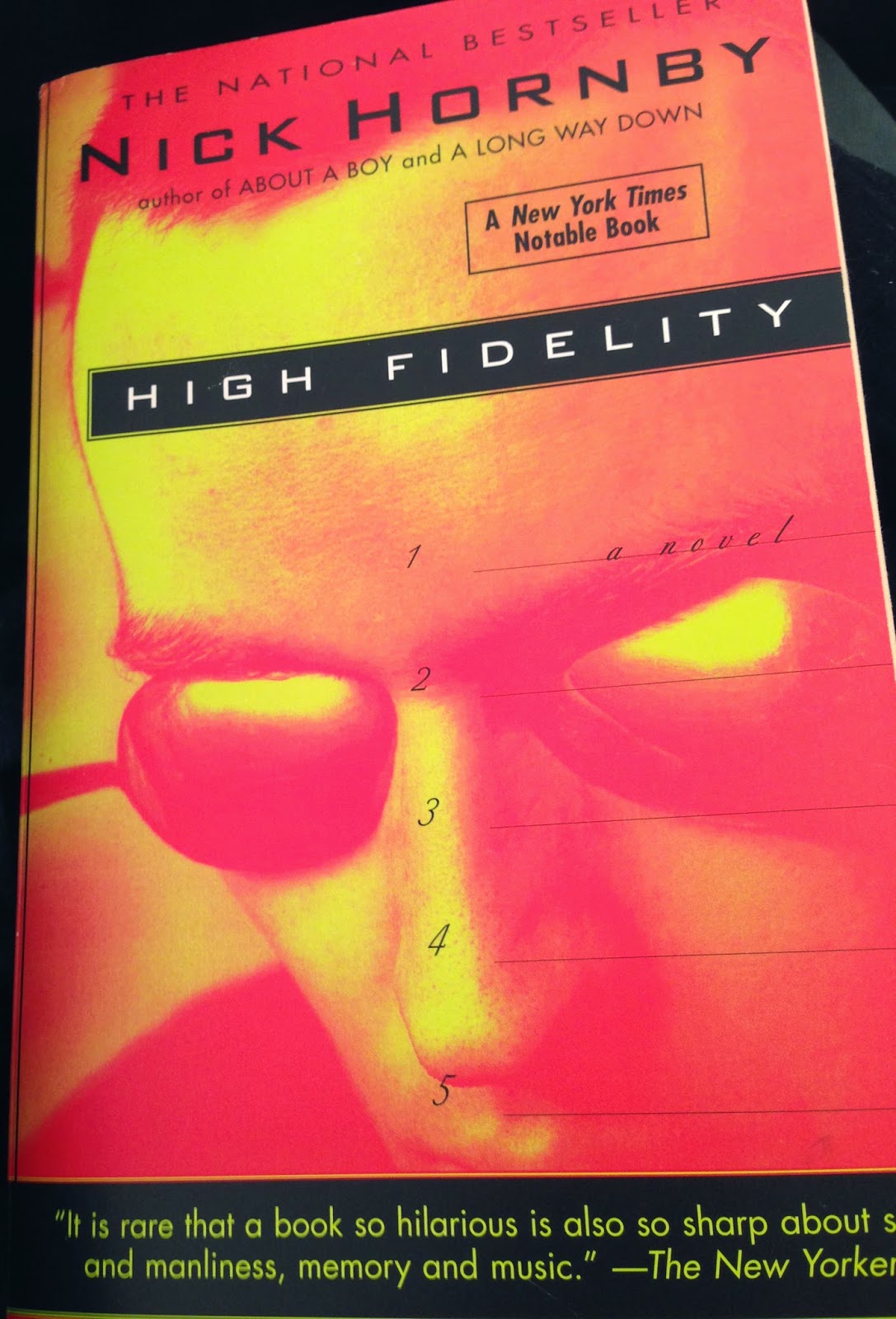

I just moved to a new place and my books are still heaped about the living room in short towers. I keep thinking about Nick Hornby's High Fidelity. Rob Fleming (or Rob Gordon as played by John Cusack in the movie) has a fairly extensive record collection that is his crowning achievement. Throughout the story, he has this ongoing ritual that seems to be a coping mechanism for the drama or disappointment of his personal life: Rob can't stop rearranging his vinyl. In his search for the perfect system--having tried alphabetically by artist and then by album name and a bunch of others--Rob begins arranging the records in chronological order of when he purchased them. The process becomes a kind of catalyst for him to reflect on his life and it inspires some of the events of Hornby's novel.

Right now, I am sitting in my new domicile, facing with the same dilemma of Rob Fleming/Rob Gordon from High Fidelity. What is that ever-elusive perfect arrangement of one's own library? In my last place, the books were arranged by size at one point, then by color later on. They've been ordered alphabetically by title and then by author. They have even been ordered by genre ranging from “analysis of astrophysics” to “surrealist/psychedelic fiction.” As with many other elements in my own life--and the Rob Fleming in me can attest to this fact--none of it seems right quite yet.

Moreover, there is a reason why my library consists of 300 books instead of a couple thousand. I lend them out or straight up give them away more often than even I, myself, would like. It's difficult to explain the urge. I have the heart of a hoarder where my books are concerned, but I also have a strong desire to create the perfect library and sometimes there's a book here or there that just doesn't quite fit in. It's a bit like trying to fix your hair in the morning and, after fighting with that one unruly strand for several minutes, you finally decide to pluck it out. It is not easy--the hair and the book are a part of me--but they simply aren't falling in line and must be gotten rid of posthaste.

Today I am considering a Fleming-esque approach to my books. Not quite chronological, but still biographical in nature, I want to arrange things according to the many phases and various obsessions of my 29 years. I begin with the collection of Hardy Boys novels I have kept since elementary school. At the time of their discovery, my family had recently moved into a new house outside of Manteca, California, and I not only discovered the joys and horrors of a dank, eerie basement, but the leavings of the prior occupants. Among the boxes of creepy, dusty dolls and rusty bicycle parts had been almost the full collection of The Hardy Boys by Franklin W. Dixon. I made it the mission of my childhood to complete the collection and, despite having outgrown the series by quite a few years, I still keep an eye out for the final two I lack whenever I go book hunting.

Within this same category, I suppose I would have to include The Chronicles of Narnia by C.S. Lewis and The Adventures of Tom Sawyer by Mark Twain. Yet this brings to mind an interesting question. Should the biography of my book collection be based solely on when I first read these books, or when I most loved them? If the latter, Tom Sawyer is still fairly current, where the Narnia books should have their place somewhere around my eighth grade year. A year of trial and uncertainty, following a move from California to Texas, in which I took comfort in the escape from our world into a world of fauns and lions and griffins and talking badgers.

This autobiographical library will not be an easy task.

And what of my comic books? I have some issues from the early nineties that should technically be squeezing themselves in between The War of the Worlds and The Jungle Book. When did Superman die again? 1992? What about when Bane broke Batman's back and Bruce had to stop wearing the cowl for a while? Surely these issues must land somewhere between the time I was devouring the writing of H.G. Wells and the time I had gotten really into reading the original stories that inspired beloved Disney films...

No, not an easy task at all. Perhaps I should go back to color-coding the covers and call it a day.

Next, I move on to an obsession with classical literature that began in my adolescence. According to the biography of my library, this began with Sherlock Holmes, but rapidly spiraled into J.D. Salinger, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Melville, Tolstoy, Miller. I remember it well. Like so much of my literary life, the urge was inspired, or perhaps “caused” is a better word choice, by music.

Like some of the people in Rob Fleming's life, I had friends of that tribe who used their knowledge of music, particularly upcoming and underground stuff, as a kind of bludgeon to browbeat the people around them into some kind of submissive or subservient position. They were that brand of nerd, the loser, or slacker who realized that the music scene existing outside of Top 40 artists gave them power. I got as caught up in this wave as I was caught up in the wave of spiritual adrenaline that went with big tent revivals and the promises of Christ. All of which I have since, gratefully, recovered from. With music, it happened rather suddenly. I recognized the band that was “it” one month was suddenly “sell out” dross the next. The fickle nature of this scene left a bad taste in my mouth and I went in search of things that would last. This search took me backward in time to things that had been proven and were still going strong. I began to read old books, the ones that you find on a New York Times must-read list. And, as for music, I began listening to early 20th-century jazz, blues, and eventually folk.

Folk brought me to Bob Dylan, Woody Guthrie, The Band, Pete Seeger, The Staples Singers, Neil Young and tons more. In literature, it brought me to Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, and Ken Kesey. I suppose this will have to be the next shelf of my library, the next subcategory. On the Road, The Dharma Bums, Desolation Angels, One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, Howl, Sailor Song, Demon Box...this era became the next obsession.

It was at this stage in my reading life that I began to seriously consider pursuing writing as a career. The words of Ginsberg and Kerouac, Kesey and, eventually, Hunter S. Thompson, ignited something in me that never cooled. Following the track and history of the Beats, I found Naked Lunch and William S. Burroughs. Following Burroughs and realizing that so many of these people were all part of one community, largely featured in Kerouac's books, made me see all the interconnecting webs of that era in literature, music, and art. Bob Dylan was inspired by Kerouac. Hunter S. Thompson was inspired by Bob Dylan. Bob Dylan was inspired by Hunter S. Thompson. Ken Kesey was featured in Thompson's Hell's Angels during a chapter set at his La Honda estate. It was an endless cycle of influence feeding into and out of itself, influencing America in kind, and eventually influencing me.

My pursuit of writing, however, did leave me kind of jaded as I rapidly began to realize that there was very little else I cared about. I couldn't imagine myself doing any other job, for example, and my late teens and early twenties were troubled as I suffered unusually powerful growing pains as a struggling writer struggling with newfound responsibilities. I had staked a lot of myself on faith because of my time in Texas, but in studying literature and pursuing creativity, I began to feel an awakening that made things about that faith not quite sit right. By the time I was 20, writing was the only thing I believed in anymore. Books, that was it. I had no religion, no patriotism, no love of money, no passion for any career outside of telling stories, and, of course, no resources, finances, credit or anything else to my name.

This is when I found the writing of Chuck Palahniuk and, in the space of five months, I read everything he had ever written. The humor of destruction, the nihilistic poetry that made light of so many of our culture's sacred trusts, and the consistently poverty-stricken characters stubbornly maintaining their outsider status both in terms of their living conditions and their intellectual outlook on life, all resonated with me.

Even now, despite having since outgrown Chuck, I find myself thinking about my library in relation to this line from Fight Club, “I had a stereo that was very decent, a wardrobe that was getting very respectable. I was close to being complete.”

This library is a sculpture – take a title or two out, add a Norman Mailer book here or a Thomas Disch novel there, and I could be complete...

As for Chuck Palahniuk, Survivor was a particular favorite as it told the story of a guy brought up in a suicide cult who lacked the faith to take his own life when the call came. Growing up religious and grappling with my own agnosticism, it just felt right.

My wandering 20th year of life took me to a town called Denton, Texas, north of Dallas, where I wound up writing my first novel. In Denton, I met Shea, who loaned me his copy of Still Life with Woodpecker by Tom Robbins. My obsession with the writings of Palahniuk ended that day and I was now vehemently, even vigorously, centered on this new set of books. I read Woodpecker in two days. Then I spent the next week at the local bookstore, unable to afford a copy of anything larger than a Jehovah's Witness pamphlet, basically stealing a chapter here or a chapter there, reading Jitterbug Perfume on the fly. Since that time, I have gotten all of Tom Robbins' books and even had the pleasure of attending a reading of his autobiography, Tibetan Peach Pie, this past June at Powell's Books.

In Tom, I found something that made me realize how narrow and juvenile the vision of Chuck Palahniuk's books had been. I saw people, like me, with the same outsider perspective, the same distrust of society's values or disconnect from social norms, but instead of being miserable about it, they were filled with wonder and daring. I realized that, like Bob Dylan said, “When you ain't got nothing, you got nothing to lose.”

I turned a corner and began to explore America, not in search of answers or something new to believe in or really anything at all, but just to go because that's what Amanda from Another Roadside Attraction would do or because that's how the great king in Jitterbug Perfume managed to live forever.

The biography of my book collection is starting to look increasingly optimistic. Filled with this new vigor, I stopped seeing things as the next scene or the next historical moment I had to devour and began to just search for what I liked. I found Neil Gaiman and read four or five of his books. I started reading books about physics and math, getting a big kick out of a little known book called Zero: The Biography of a Dangerous Idea by Charles Seife in which I learned about the tug-of-war between math and religion going back to when Time was still in diapers. Then, much later than I should have, I finally got around to Douglas Adams' The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy and, embracing a lifelong love of science fiction, got into Philip K. Dick, Orson Scott Card, and tons more.

Not long after, I wrote Dystopia Boy, my own addition to the annals of science fiction and a love note to everyone on my book shelf. I learned how to add danger to my voice by obsessing on Hunter S. Thompson for a while. I found humanity through Tom Robbins. I found music and poetry and that lowdown eloquence of the poor from listening to too much Bob Dylan and reading too much Kerouac. J. D. Salinger taught me how to talk in my writing rather than just speak. Palahniuk showed me how the incendiary can be hilarious. And my love of the classics held up the firm belief that if something is good, it is timeless, if the writer does his job right, it never suffers the fate of so many bands that my old friends liked for a minute and cast aside like autumn leaves the next.

Like Rob Fleming's vinyl collection, I can see my life in the literature I've consumed. I have often been a little behind the trends, but typically that's just because I want to make sure what I'm spending my time on is going to last. It's just another variation on the eternal question Tom Robbins asked all those years ago: How do we make love stay?

Trevor D. Richardson is the founder and editor of The Subtopian and the author of American Bastards, Honeysuckle & Irony, and Dystopia Boy: The Unauthorized Files from Montag Press. A West Coast man by birth, Trevor was brought up in Texas and has since ventured back west and put down roots in Portland, Oregon. His numerous short stories have appeared in magazines like Word Riot, Underground Voices, and a science fiction anthology called Doomology: The Dawning of Disasters.

My Library is an intimate look at personal book collections. Readers are encouraged to send high-resolution photos of their home libraries or bookshelves, along with a description of particular shelving challenges, quirks in sorting (alphabetically? by color?), number of books in the collection, and particular titles which are in the To-Be-Read pile. Email thequiveringpen@gmail.com for more information.

Saturday, March 2, 2013

Soup and Salad: Covering Fahrenheit 451, More covers at The Casual Optimist, Ayana Mathis and the "Aha! Moment," Retiring writers, Delayed reviews, Heavy-breathing reviews, Adam Braver's new project, 100 years of bestsellers, Paperback pride, First drafts

On today's menu:

1. Congratulations to Matthew Owen who won a contest, sponsored by Simon & Schuster and the American Library Association’s Office for Intellectual Freedom, to design a new cover for Ray Bradbury's Fahrenheit 451. Owen's concept (seen above) is simple and brilliant and is sure to draw new readers to the special 60th anniversary printing of Bradbury's classic. I suspect those who already own Fahrenheit 451 will also buy a copy just to have this beautiful art on their shelves.

2. Speaking of outstanding design, if you aren't already a subscriber to The Casual Optimist blog, you should start now. I always look forward to visiting the site for a full course of smart conversation about eye candy--like the British cover design for Laurent Binet's novel HHhH (which, if you'll recall, was reviewed here at The Quivering Pen by Sam Thomas not too long ago).

3. At The Millions, Matthew Bourne describes how, in his research for an article for Poets & Writers magazine, he visited the "sun-struck jewel box" office of literary agent Ellen Levine to talk about her "Aha! Moment"--that is, "the moment the light went on for [her] about a particular manuscript, the moment when [she] thought, I have to do this project."

As we sat down to discuss the page in question, midway into the first chapter of a first novel by an unknown African-American writer living in Brooklyn, Levine described the writer’s command of language and storytelling craft, but when she reached a key passage in the scene, in which a young mother is about to lose her twin babies to pneumonia, Levine’s voice caught. When I looked up, her eyes had misted over. If you interview a lot of people, you develop a radar for when people are selling and when they are not, and in this case Ellen Levine was not selling. She was genuinely moved by this scene in an unpublished book by a writer nobody had ever heard of. I left her office that day thinking: Something really, really good is going to happen to that book. Sure enough, eight months later, I read that the book Levine and I had been discussing that day, The Twelve Tribes of Hattie by Ayana Mathis, had been published in December, six weeks ahead of schedule, and had been picked by Oprah Winfrey for her newly rebooted Book Club.Bourne goes on to talk about what we've come to know as the Oprah Fairy Tale Effect: "the sudden reversal of fortune experienced by those lucky few Oprah authors. The poor wretched scribe....toiling away in obscurity in the backwaters of American literary culture until one day the phone rings, and — Oh, my God! — 'Hi, this is Oprah.'"

4. Elsewhere at The Millions, Bill Morris ponders the question "Can writers retire?" The abrupt end (and in some cases only a pause) of some writers' careers are called into question, including those of Alice Munro, E. M. Forester, J. D. Salinger, Roberto Bolano and Phillip Roth, the latest writer to hang up his pen.

5. On any given day, you'll find me writhing in agony over the fact that I'm not reviewing books as soon as I finish reading them. I have every good intention of sitting down and opining about a book as soon as I turn the last page. Alas, time and circumstance conspire against me, and I often end up not posting a review here at the blog. In fact, at this very moment, I have at least five novels begging for my attention, even though enough time has elapsed to turn their details into fuzzy mush. Regrets, I've had a few. That's why I was happy to see Rena Rossner write a review of Jessica Keener's debut novel Night Swim....one year after the fact:

I read the book in nearly one sitting – I could not put it down. At the time, I really wanted to write a review of the book, but life got hectic, as it tends to do, and I never got around to it. When I saw Jessica post recently on Facebook that she was celebrating her book’s 1-year anniversary with a 50-state Skype book-club blog tour, I realized that even though I read the book a year ago, so many things still stuck in my mind. And that made me think, wouldn’t that make a great blog post? To talk about a book one year later and specifically highlight the things that stayed with you. What higher compliment to pay an author than to be able to say: “I still remember…”As an author, I think this is a wonderful way to pay tribute to a book, talking about the specific details which still float sharp and bright on the surface of that fuzzy mush we call memory.

6. Sometimes, like with Rossner's blog post, reviewers can pull me in with their heavy-breathing earnestness. At Three Guys One Book, Joseph Rakowski did just that as he opened his review of Mark SaFranko's novel No Strings with this:

Have you ever shot a potato gun, held a Roman candle firework, or lit a propane grill? Then you’ve had the feeling. That feeling right before you light it, the feeling that something is about to go terribly wrong. Well, that point never came during SaFranko’s latest novel No Strings. It built, and built, and almost blew up, but it didn’t. It worked perfectly, just like it was supposed to. The potato shot a mile, the Roman candle did its Jack Kerouac thing, and the grill is fired up and ready to cook. I was in the tub when I finished reading No Strings…note pad balanced on the soap bar rack. My plan to finish the book, dry off, get ready for the day, and write the review. I am currently dripping wet, sitting at my desk, wiping droplets of wet soap slime from my elbows as I type.How could I possibly resist Rakowski's eagerness to sell me on the book? I couldn't--I went right out and bought it.

7. As readers of this blog know, I'm a big fan of Adam Braver's novels (like Misfit and Mr. Lincoln's Wars), so when Adam wrote to me telling of his latest project, I was intrigued. He told me in the email that The Madrid Conversations was a special project he and co-author Molly Gessford worked to bring to print: "It's all been a labor of love that needs a little more love." Subtitled "Normando Hernández González: Persecuted, Imprisoned, Exiled," the book is a transcript of interviews Braver and Gessford conducted with Gonzalez, who was among seventy-five Cuban journalists arrested in the "Black Spring," then were tried and sentenced to Cuba's harshest prisons. I haven't had a chance to read The Madrid Conversations, but I wanted to mention it here as something worth your attention. By the way, Braver said he's taking no money for the book--all proceeds go to Gonzalez himself.

8. My hat is off to blogger Matt Kahn who recently announced he would review every book to reach the No. 1 spot on the Publishers Weekly annual bestsellers list, starting in 1913. That's right, Kahn is going to subject himself to 100 years of dubious-quality literature--from Winston Churchill to E. L. James. God give him strength on his journey.

9. I'll never forget the moment I first learned Fobbit had been accepted for publication by Grove/Atlantic. The good news: Fobbit was going to be published! (cue the bombs bursting in mid-chest) The bad news: it would be published in trade paperback rather than hardcover. (cue the sound of fizzled fireworks) Ah, but was that really bad news? I'll admit the idea of forsaking hardcover publication gave me a moment's blink of disappointment. But only for a moment because I had seen plenty of "trade paper originals" pass across my reviewer's desk from respectable publishers who gave them just as much attention and love as their sexier "grown-up" hardcover siblings. It wasn't long before I came to be proud of my TPO status and couldn't imagine Fobbit launching in any other format (though in one month's time it will indeed be published in hardcover in the UK by Harvill-Secker. Re-ignite the fireworks!!). So that's why I was interested to read this article in the Virginia Quarterly Review: "Oh Format, Where Art Thou?" in which Kathleen Schmidt reassures us that softcover is nothing to be ashamed of:

[W]hat is an author to do when the choice is to be published in trade paperback or e-book, but not hardcover? For some, the choice is complex because being published in hardcover (falsely) assigns a certain amount of stature to said author. In the past, a hardcover was considered a calling card for an author while a trade paperback was akin to a napkin on which you’d scribble your number. Times have changed, as has the consumer. In other words, the format that sells is the right format for the book.

10. It's always fun to take the backs off of writers and examine the way the gears whir and click. At The Millions, Edan Lepucki gathers the thoughts of other authors on first drafts, shitty and otherwise. Jennifer Egan, Emily St. John Mandel, Emma Straub, Ben Fountain, Antoine Wilson, and others let us inside The Process.

Labels:

Fobbit,

J. D. Salinger,

Judging a Book,

Ray Bradbury,

Soup and Salad

Monday, December 10, 2012

My First Time: Jen Michalski

My First Time is a regular feature in which writers talk about virgin experiences in their writing and publishing careers, ranging from their first rejection to the moment of holding their first published book in their hands. Today’s guest is Jen Michalski, author of the novel The Tide King (winner of the 2012 Big Moose Prize), the short story collections From Here and Close Encounters, and the novella collection Could You Be With Her Now which is coming from Dzanc Books next month. Her work has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize. She is the founding editor of the literary quarterly jmww, a co-host of The 510 Readings and the biannual Lit Show, and interviews writers at The Nervous Breakdown. She also is the editor of the anthology City Sages: Baltimore, which Baltimore Magazine called a "Best of Baltimore" in 2010. Follow her on Twitter here.

The First Spy I Loved

When I was younger, bands like REM, The Pixies, and Siouxsie and the Banshees crowded my mix tapes, and Salinger, Bukowski, and Kerouac lined my bookshelves. I thought I was queen shit. It wasn’t until I was older when I realized that the bands I listened to uncritically as a child, like Fleetwood Mac, with their perfect pop, emotional masterpiece Rumors and new-wave forerunner Tusk, influenced my music pedigree way more than the cool kids from Sire and Matador Records. And it wasn’t until I was way, way older when I realized the book that influenced me most as a reader and writer was not some Faulknerian or Russian masterpiece, anything written by Gertrude Stein, or even some stream-of-conscious beat paperback but a children’s book—about a girl who wants to be a spy.

My aunt bought me Harriet the Spy by Louise Fitzhugh when I was ten. She had gone to Virginia Beach for vacation and, awesomely, returned with books for my brother and me that she’d gotten at a beach bookstore. Because my aunt looked—and still looks—young for her age, the shop clerk assumed the books were for her and thought she might like The Secret Garden, Bunnicula, and Harriet the Spy.

If I were a different kind of girl, this essay would probably be about The Secret Garden (Bunnicula, about a vampire bunny, was more my brother’s expertise). But I was a voracious reader and tomboy, and Harriet the Spy appealed to both of those traits. Harriet M. Welsch, an 11-year-old girl who lives on the Upper East Side in the 1950s, wants to be a spy. After school, she dons a disguise (a sweatshirt, jeans, and an old pair of father’s glasses), and with a pocket notebook and homemade utility belt, she spies on different families in her neighborhood. She also writes about her friends Sport and Janie, her classmates at a private day school, her parents (a television executive and socialite), and her nanny (a mannish but insightful woman that Harriet calls Ole Golly). When her friends find and read her notebook, full of honest but sometimes hurtful assessments about them, she is shunned and tormented and must learn the power of humility and asking for forgiveness.

Harriet the Spy was a mind-blower to a shy but curious girl like me who read all 56 hardcover Nancy Drew novels the summer before, courtesy of the Baltimore County Public Library. And the similarities were uncanny: Like Nancy, Harriet was cared for by a somewhat-matronly woman who was not her mother. Like Nancy, Harriet was allowed freedoms of which I could only dream. Unlike Nancy, however, Harriet did not act like a lady. She was loud and impulsive and sometimes petty. She did not go to homecoming with a special male friend, Ned Nickerson. She liked routine (evidenced by her daily spy route and insistence on tomato and mayonnaise sandwiches for lunch and cake and milk after school). Her friends were a boy, Sport, who lived with his father and assumed all the household duties, including clipping coupons and shopping, and a girl, Janie, who wanted to blow up the world instead of taking dance lessons.

Unlike the industrious Ingalls in Little House on the Prairie and the thoughtful Browns in Encyclopedia Brown, Harriet’s parents were absent and somewhat shallow, more interested in the entertainment industry, cocktails, and gossip than their inquisitive, high-strung young daughter. They were, in some ways, like my parents. They had scary fights and were preoccupied and dismissive at times. They smoked and drank and were oblivious to the teasing I got from being overweight by the mean, oversexed boys in the fifth grade who listened to AC/DC and showed the prettier girls their penises. In other words, they were real people, imperfect and possibly stunted but hopefully always evolving.

But Fitzhugh’s realism didn’t stop there. When Harriet’s notebook is discovered and she is punished by her peers, it is not because of a dichotomous, black-and-white transgression so often presented in those After-School specials on TV. It’s because she’s curious about her world and, most unforgivable of all, honest. She doesn’t write about her friends and neighbors in her notebook to slander them; she writes to make sense of the same pettiness, selfishness, and uncertainly that plague them all. The world, unlike stories, doesn’t wrap up neatly forever ever after. Not only may Harriet lose her friends for good, more importantly, to avoid such catastrophes in the future, her nanny Old Golly warns, “[S]ometimes you have to lie. But to yourself you must always tell the truth.”

I don’t know if I could have been friends with Harriet. I would’ve been drawn to her fearlessness, her feminist-approved career goals and friends (I haven’t really touched on the gay subtexts of Fitzhugh’s stories, but suffice to say, they were of great interest to me as well), and she may have gotten less abrasive as she grew older but, let’s face it—she was spoiled and a bully. I probably would have spent more time running home, vowing we would never be friends again, rather than accompanying her on her routes. Not that she would have wanted me, anyway. Harriet was a spy; she worked alone.

So do writers. Like Harriet, I write to make sense of my world, my emotions, my relationships, and my desires. Like Harriet, I have kept a diary, then a journal, since I learned to write and began writing novels back in the fifth grade, when I laboriously wrote with thin magic markers on the back of office memos my mother brought home from work for my brother and me to use as drawing paper. Ten pages of the story would be written in green, then five in blue, then several more in red as the markers dried out but the stories continued. Although I did not spy on others, I meticulously detailed my interactions with people in everyday settings and important events, punctuating each entry with “I will never forget this day.”

Inevitably, those diaries are gone, those days, ironically, forgotten. But even then, like Harriet, I understood on some level the need to preserve and dissect my experiences, to cull the threads and insights from them. I learned that truth is stranger than fiction, and what makes a good story is not the plot but the sense, no matter how flawed they are, that the characters are true to themselves. And that the worlds I create should always immerse me (and the reader) the same way Fitzhugh’s Upper East side enchanted me, with its the corner delis, palatial brownstones like Harriet’s (with her own bathroom), drug stores with egg creams. Where the rules of games and life were toughed out on the grounds of Carl Schurz Park, worlds in which alliances are tenuous and ever-changing, where children are tender and brutal. Where there are no winners or losers but draws and uneasy stalemates. It is the childhood I remember, albeit not the one I remember reading in children’s books. Except in Harriet the Spy. Louise Fitzhugh, in keeping it real, gave me the green light to do the same.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)