Showing posts with label Larry Brown. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Larry Brown. Show all posts

Thursday, August 22, 2019

Front Porch Books: August 2019 edition

Front Porch Books is a monthly tally of new and forthcoming books—mainly advance review copies (aka “uncorrected proofs” and “galleys”)—I’ve received from publishers. Cover art and opening lines may change before the book is finally released. I should also mention that, in nearly every case, I haven’t had a chance to read these books, but they’re definitely going in the to-be-read pile.

Tiny Love

by Larry Brown

(Algonquin Books)

Jacket Copy: A career-spanning collection, Tiny Love brings together for the first time the stories of Larry Brown’s previous collections along with those never before gathered. The self-taught Brown has long had a cult following, and this collection comes with an intimate and heartfelt appreciation by novelist Jonathan Miles. We see Brown's early forays into genre fiction and the horror story, then develop his fictional gaze closer to home, on the people and landscapes of Lafayette County, Mississippi. And what’s astonishing here is the odyssey these stories chart: Brown’s self-education as a writer and the incredible artistic journey he navigated from “Plant Growin’ Problems” to “A Roadside Resurrection.” This is the whole of Larry Brown, the arc laid bare, both an amazing story collection and the fullest portrait we’ll see of one of the South’s most singular artists.

Opening Lines: Jerry Barlow eased the ’67 Sportster to the edge of the sand road and shut off the motor. He listened closely to the silence of the woods. Aside from the voices of a few mockingbirds and blue jays crouched in the leaves of blackjack oak and scrub pine, nothing could be heard except the ticking of his hot motor. He got off and unstrapped the short-handled hoe and the gallon jug of liquid plant food from the chrome sissy bar.

He knew Bacon County, Georgia, was a dangerous place to be doing what he was doing, but he was sure he wouldn't get caught.

Blurbworthiness: “Larry Brown wrote stories that captured both the beauty and the brokenness of life. He never blinked at life’s darkness, but drew you into it with his characters. Larry Brown wrote the way the best singers sing: with honesty, grit, and the kind of raw emotion that stabs you right in the heart. He was a singular American treasure.” (Tim McGraw)

The Topeka School

by Ben Lerner

(Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

Jacket Copy: Adam Gordon is a senior at Topeka High School, class of ’97. His mother, Jane, is a famous feminist author; his father, Jonathan, is an expert at getting “lost boys” to open up. They both work at a psychiatric clinic that has attracted staff and patients from around the world. Adam is a renowned debater, expected to win a national championship before he heads to college. He is one of the cool kids, ready to fight or, better, freestyle about fighting if it keeps his peers from thinking of him as weak. Adam is also one of the seniors who bring the loner Darren Eberheart―who is, unbeknownst to Adam, his father’s patient―into the social scene, to disastrous effect. Deftly shifting perspectives and time periods, The Topeka School is the story of a family, its struggles and its strengths: Jane’s reckoning with the legacy of an abusive father, Jonathan’s marital transgressions, the challenge of raising a good son in a culture of toxic masculinity. It is also a riveting prehistory of the present: the collapse of public speech, the trolls and tyrants of the New Right, and the ongoing crisis of identity among white men.

Opening Lines: Darren pictured shattering the mirror with his metal chair. From TV he knew there might be people behind it in the dark, that they could see him. He believed he felt the pressure of their gazes on his face. In slow motion, a rain of glass, the presences revealed. He paused it, rewound, watched it fall again.

The man with the black mustache kept asking him if he wanted something to drink and finally Darren said hot water.

Blurbworthiness: “In Ben Lerner’s riveting third novel, Midwestern America in the late nineties becomes a powerful allegory of our troubled present. The Topeka School deftly explores how language not only reflects but is at the very center of our country’s most insidious crises. In prose both richly textured and many-voiced, we track the inner lives of one white family’s interconnected strengths and silences. What’s revealed is part tableau of our collective lust for belonging, part diagnosis of our ongoing national violence. This is Lerner’s most essential and provocative creation yet.” (Claudia Rankine, author of Citizen: An American Lyric)

The Ghosts of Eden Park

by Karen Abbott

(Crown)

Jacket Copy: In the early days of Prohibition, long before Al Capone became a household name, a German immigrant named George Remus quits practicing law and starts trafficking whiskey. Within two years he’s a multi-millionaire. The press calls him “King of the Bootleggers,” writing breathless stories about the Gatsby-esque events he and his glamorous second wife, Imogene, host at their Cincinnati mansion, with party favors ranging from diamond jewelry for the men to brand-new cars for the women. By the summer of 1921, Remus owns 35 percent of all the liquor in the United States. Pioneering prosecutor Mabel Walker Willebrandt is determined to bring him down. Willebrandt’s bosses at the Justice Department hired her right out of law school, assuming she’d pose no real threat to the cozy relationship they maintain with Remus. Eager to prove them wrong, she dispatches her best investigator, Franklin Dodge, to look into his empire. It’s a decision with deadly consequences. With the fledgling FBI on the case, Remus is quickly imprisoned for violating the Volstead Act. Her husband behind bars, Imogene begins an affair with Dodge. Together, they plot to ruin Remus, sparking a bitter feud that soon reaches the highest levels of government--and that can only end in murder. Combining deep historical research with novelistic flair, The Ghosts of Eden Park is the unforgettable, stranger-than-fiction story of a rags-to-riches entrepreneur and a long-forgotten heroine, of the excesses and absurdities of the Jazz Age, and of the infinite human capacity to deceive.

Opening Lines: He had been waiting for that morning, dreading it, aware it couldn’t be stopped. An hour ago he was eating breakfast and now here he was, chasing her through Eden Park.

Blurbworthiness: “Prose so rich and evocative, you feel you’re living the story—and full of lots of ‘I didn’t know that’ moments. Gatsby-era noir at its best.” (Erik Larson, author of Devil in the White City)

The Body

by Bill Bryson

(Doubleday)

Jacket Copy: Bill Bryson once again proves himself to be an incomparable companion as he guides us through the human body—how it functions, its remarkable ability to heal itself, and (unfortunately) the ways it can fail. Full of extraordinary facts (your body made a million red blood cells since you started reading this) and irresistible Bryson-esque anecdotes, The Body will lead you to a deeper understanding of the miracle that is life in general and you in particular. As Bill Bryson writes, “We pass our existence within this wobble of flesh and yet take it almost entirely for granted.” The Body will cure that indifference with generous doses of wondrous, compulsively readable facts and information.

Opening Lines: Long ago, when I was a junior high school student in Iowa, I remember being taught by a biology teacher that all the chemicals that make up a human body could be bought in a hardware store for $5.00 or something like that. I don’t recall the actual sum. It might have been $2.97 or $13.50, but it was certainly very little even in 1960s money, and I remember being astounded at the thought that you could make a slouched and pimply thing such as me for practically nothing.

Tell Me Who We Were

by Kate McQuade

(William Morrow)

Jacket Copy: It begins with a drowning. One day Mr. Arcilla, the romance language teacher at Briarfield, an all-girls boarding school, is found dead at the bottom of Reed Pond. Young and handsome, the object of much fantasy and fascination, he was adored by his students. For Lilith and Romy, Evie and Claire, Nellie and Grace, he was their first love, and their first true loss. In this extraordinary collection, Kate McQuade explores the ripple effect of one transformative moment on six lives, witnessed at a different point in each girl’s future. Throughout these stories, these bright, imaginative, and ambitious girls mature into women, lose touch and call in favors, achieve success and endure betrayal, marry and divorce, have children and struggle with infertility, abandon husbands and remain loyal to the end. Lyrical, intimate, and incisive, Tell Me Who We Were explores the inner worlds of girls and women, the relationships we cherish and betray, and the transformations we undergo in the simple act of living.

Opening Lines: We were all a little bit in love with her.

Partly the good of her, and partly the bad. Partly the pretty, and partly the dark thing under the pretty.

Blurbworthiness: “The stories in Tell Me Who We Were are united by ferociously complicated women wrestling with pain and desire in a vividly unsettled world. Kate McQuade is a spectacular writer, equal parts sensitive and fearless, and Tell Me Who We Were is abundant with heartbreak and wonder.” (Laura Van Den Berg, author of Find Me)

A Good Neighborhood

by Therese Anne Fowler

(St. Martin’s)

Jacket Copy: In Oak Knoll, a verdant, tight-knit North Carolina neighborhood, professor of forestry and ecology Valerie Alston-Holt is raising her bright and talented biracial son. Xavier is headed to college in the fall, and after years of single parenting, Valerie is facing the prospect of an empty nest. All is well until the Whitmans move in next door―an apparently traditional family with new money, ambition, and a secretly troubled teenaged daughter. Thanks to his thriving local business, Brad Whitman is something of a celebrity around town, and he’s made a small fortune on his customer service and charm, while his wife, Julia, escaped her trailer park upbringing for the security of marriage and homemaking. Their new house is more than she ever imagined for herself, and who wouldn’t want to live in Oak Knoll? But with little in common except a property line, these two very different families quickly find themselves at odds: first, over an historic oak tree in Valerie’s yard, and soon after, the blossoming romance between their two teenagers. Told in multiple points of view, A Good Neighborhood asks big questions about life in America today―what does it mean to be a good neighbor? How do we live alongside each other when we don’t see eye to eye?―as it explores the effects of class, race, and heartrending star-crossed love in a story that’s as provocative as it is powerful.

Opening Lines: An upscale new house in a simple old neighborhood. A girl on a chaise beside a swimming pool, who wants to be left alone. We begin our story here, in the minutes before the small event that will change everything. A Sunday afternoon in May when our neighborhood is still maintaining its tenuous peace, a loose balance between old and new, us and them. Later this summer when the funeral takes place, the media will speculate boldly on who’s to blame. They’ll challenge attendees to say on-camera whose side they’re on.

For the record: we never wanted to take sides.

Blurbworthiness: “A gripping modern morality tale...Familiar elements―two families, two young lovers, a legal dispute―frame a story that feels both classic and inevitable. But Fowler makes the book her own with smart dialogue, compelling characters and a communal “we” narrator that implicates us all in the wrenching conclusion.” (Tara Conklin, author of The Last Romantics)

Edison

by Edmund Morris

(Random House)

Jacket Copy: Although Thomas Alva Edison was the most famous American of his time, and remains an international name today, he is mostly remembered only for the gift of universal electric light. His invention of the first practical incandescent lamp 140 years ago so dazzled the world—already reeling from his invention of the phonograph and dozens of other revolutionary devices—that it cast a shadow over his later achievements. In all, this near-deaf genius (“I haven’t heard a bird sing since I was twelve years old”) patented 1,093 inventions, not including others, such as the X-ray fluoroscope, that he left unlicensed for the benefit of medicine. One of the achievements of this staggering new biography, the first major life of Edison in more than twenty years, is that it portrays the unknown Edison—the philosopher, the futurist, the chemist, the botanist, the wartime defense adviser, the founder of nearly 250 companies—as fully as it deconstructs the Edison of mythological memory. Edmund Morris, winner of the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award, brings to the task all the interpretive acuity and literary elegance that distinguished his previous biographies of Theodore Roosevelt, Ronald Reagan, and Ludwig van Beethoven. A trained musician, Morris is especially well equipped to recount Edison’s fifty-year obsession with recording technology and his pioneering advances in the synchronization of movies and sound. Morris sweeps aside conspiratorial theories positing an enmity between Edison and Nikola Tesla and presents proof of their mutually admiring, if wary, relationship. Enlightened by seven years of research among the five million pages of original documents preserved in Edison’s huge laboratory at West Orange, New Jersey, and privileged access to family papers still held in trust, Morris is also able to bring his subject to life on the page—the adored yet autocratic and often neglectful husband of two wives and father of six children. If the great man who emerges from it is less a sentimental hero than an overwhelming force of nature, driven onward by compulsive creativity, then Edison is at last getting his biographical due.

Opening Lines: Toward the end, as at the beginning, he lived only on milk.

Even when he turned eighty-four in February, and pretended to be able to hear the congratulations of the townspeople of Fort Myers, and let twenty schoolgirls in white dresses escort him under the palms to the dedication of a new bridge in his name, and shook his head at being called a “genius” by the governor of Florida, and gave a feeble whoop as he untied the green-and-orange ribbon, and retreated with waves and smiles to the riverside estate he and Mina co-owned with the Henry Fords, he declined a slice of double-iced birthday cake and instead drank the fourth of the seven pints of milk, warmed to nursing temperature, that daily soothed his abdominal pain.

We Leave the Flowers Where They Are

by Richard Fifield (editor)

(Sweetgrass Books)

Jacket Copy: Longtime memoir instructor and novelist Richard Fifield of Missoula, Montana has curated an anthology, We Leave The Flowers Where They Are, named after a line in the single poem included in the book. Fifield is the author of The Flood Girls and The Small Crimes Of Tiffany Templeton. The idea for the project grew out of Fifield’s memoir classes. Women of all ages and backgrounds have been writing and sharing their stories in his classes for years, according to Fifield, who says “it is time to share these stories with a broader audience.” The anthology is a truly diverse collection, with stories from women all around the Big Sky State, from Powder River to Eureka. Reflecting the lives of all Montana women, the authors’ stories offer joy, pain, humor and hope. From the story of how a midwife in Montana was sued and fought in court to ultimately earn the first professional license issued by the state, to the memoir of an incarcerated woman diagnosed with AIDS, the anthology represents the voices of writers with stories that demand to be told. Fifield’s hope is that these memoirs will help other women to not feel alone, ashamed, and to believe that change is possible. A portion of the book’s proceeds will benefit two nonprofit organizations: Zootown Arts Community Center, an arts nonprofit based in Missoula, and Humanities Montana, a nonprofit affiliate of the National Endowment for the Humanities with offices around the state.

Opening Lines: When the phone rings in the middle of the night, I turn on a small light, and it wakes my husband. It is just after two in the morning. He turns over in the bed, accustomed to these late night calls. Sarah is in labor, and I must go to work. After years as a midwife, the rush of an impending birth jolts me awake, and I move quickly, a familiar routine, but still exciting every time. (from “Number One” by Dolly Browder)

The Life and Afterlife of Harry Houdini

by Joe Posnanski

(Avid Reader Press)

Jacket Copy: Harry Houdini. Say his name and a number of things come to mind. Escapes. Illusions. Magic. Chains. Safes. Live burials. Close to a century after his death, nearly every person in America knows his name from a young age, capturing their imaginations with his death-defying stunts and daring acts. He inspired countless people, from all walks of life, to find something magical within themselves. This is a book about a man and his extraordinary life, but it is also about the people who he has inspired in death. As Joe Posnanski delves into the deepest corners of Houdini-land, visiting museums (one owned by David Copperfield), attractions, and private archives, he encounters a cast of unforgettable and fascinating characters: a woman who runs away from home to chase her dream of becoming a magician; an Italian who revives Houdini’s most famous illusion every night; a performer at the Magic Castle in Los Angeles who calls himself Houdini’s Ghost; a young boy in Australia who, one day, sees an old poster and feels his life change; and a man in Los Angeles whose sole mission is life has been to keep the legend’s name alive. Both a personal obsession and an odyssey of discovery, Posnanski draws inspiration from his lifelong passion for and obsession with magic, blending biography, memoir, and first-person reporting to examine Harry Houdini’s life and legacy. This is the ultimate journey to uncover why this magic man endures, and what he still has to teach the world about wonder.

Opening Lines: “Ladies and gentlemen,” Harry Houdini sang, for in those days he did sing. Houdini’s voice in many way was more magical than any escape or illusion. He spent a lifetime cultivating it, smoothing it, flattening out the Hungarian accent, cleaning up the new York street grime, transforming every da into the, dees into these, and ain’t into are not. By the time he became famous around the world―and by 1915 he was famous in more countries than any performer on earth―you could hear European high society in the street urchin’s voice.

Not a Thing to Comfort You

by Emily Wortman-Wunder

(University of Iowa Press)

Jacket Copy: From a lightning death on an isolated peak to the intrigues of a small town orchestra, the glimmering stories in this debut collection explore how nature—damaged, fierce, and unpredictable—worms its way into our lives. Here moths steal babies, a creek seduces a lonely suburban mother, and the priorities of a passionate conservationist are thrown into confusion after the death of her son. Over and over, the natural world reveals itself to be unknowable, especially to the people who study it most. These tales of scientists, nurses, and firefighters catalog the loneliness within families, betrayals between friends, and the recurring song of regret and grief.

Opening Lines: The woman crawled into town from the riverbed. Two miles. The elbows of her jean jacket were ripped to shreds and there was tar on her forearms, and gravel, and river mud. That’s how it was we knew how far she’d come. That, and the other body, the man’s, was found down in the tamarisk, catfish gnawing on his feet. We knew they were together because they each had part of the same animal skull in a pocket: she had the cranial cavity and upper mandible; he had the jaw. I put hers on her nightstand so it’d be the first thing she saw when she woke up.

Blurbworthiness: “Populated with all manner of wild animals, endangered species, and flawed people, the endlessly readable stories in Not a Thing to Comfort You remind me of campfire ranger talks, if the rangers are Annie Proulx or Raymond Carver and the untended campfire burns down an entire forest. Wortman-Wunder now certainly enters the ranks of our finest naturalist writers, yet what gives these stories their remarkable power and depth is her lifetime of meticulous fieldwork on the always unpredictable human heart.” (Justin Hocking, author, The Great Floodgates of the Wonderworld: A Memoir)

Sweep Out the Ashes

by Mary Clearman Blew

(University of Nebraska Press)

Jacket Copy: Diana Karnov came to Versailles, Montana to uncover secrets. Teaching college history in remote northern Montana offers the opportunity to put distance between herself and her overbearing great-aunts and to uncover information about her parents, especially the father she can’t even remember. At first overwhelmed by the brutal winter, Diana throws herself into exploring mysteries her aunts refuse to explain. Eventually, she befriends several locals, including a student, Cheryl Le Tellier, and her brother, Jake. As Diana’s relationship with Jake deepens, he discusses his Métis heritage and culture, exposing the enormous gaps in her historical knowledge. Astounded, Diana begins to understand that American narratives, what she learns about her father, and the capacity for women to work and learn is not as set and certain as she was taught. Mary Clearman Blew deftly balances these 1970s pressure points with multifaceted characters and a layered romance to deliver an instant Western classic.

Opening Lines: Diana Karnov stood at the classroom window, looking out over the faculty parking lot in the early twilight of Montana’s northern latitude. Beyond the parking lot stretched the frostbitten brown grass of the Lawn, ringed by a glow of lights like a barrier between the campus and the open prairie. As the afternoon faded into nightfall, her own reflection emerged in the glass like a ghost of herself superimposed upon an unforgiving landscape.

Blurbworthiness: “Smart, witty, hard-hitting, tender, and compelling. . . . Much more than a saga about women struggling for their rightful place in the world, though, this book stages a fascinating love story, a fresh look at ethnic relations, and an exciting exploration of history and its surprising revelations. It’s a damned good read.” (Joy Passanante, author of Through a Long Absence: Words from My Father’s Wars)

Vera Violet

by Melissa Anne Peterson

(Counterpoint)

Jacket Copy: Vera Violet recounts the dark story of a rough group of teenagers growing up in a twisted rural logging town. There are no jobs. There is no sense of safety. But there is a small group of loyal friends, a truck waiting with the engine running, a pair of boots covered in blood, and a hot 1911 with a pearl pistol grip. Vera Violet O’Neely’s home is in the Pacific Northwest—not the glamorous scene of coffee bars and craft beers, but the hardscrabble region of busted pickups and broken dreams. Vera’s mother has left, her father is unstable, and her brother is deeply troubled. Against this gritty background, Vera struggles to establish a life of her own, a life fortified by her friends and her hard-won love. But the relentless poverty coupled with the twin lures of crystal meth and easy money soon shatter fragile alliances. Her world violently torn apart, Vera is forced to leave everything behind and move to St. Louis, Missouri. She settles into a job at an inner-city school where she encounters the same disarray of community. And alone in her small apartment, Vera grieves. She thinks about her family and the love of her life, Jimmy James Blood. In this brilliant, explosive debut, Melissa Anne Peterson establishes herself as a fresh, raw voice, a writer to be reckoned with.

Opening Lines: The Montana sky opened up and gave me snow. Snow to numb my wounds. Snow to cover my footprints. Snow to cushion the echo of the rifle as I fired it repeatedly.

Blurbworthiness: “Vera Violet is the most authentic and exciting debut I’ve read in a long time. At once gritty and jaw-droppingly lyrical, Peterson’s voice is a clarion call for the downtrodden and disenchanted. Reading Vera Violet is nothing less than a visceral and stirring experience.” (Jonathan Evison, author of Lawn Boy)

Deacon King Kong

by James McBride

(Riverhead)

Jacket Copy: In September 1969, a fumbling, cranky old church deacon known as Sportcoat shuffles into the courtyard of the Cause Houses housing project in south Brooklyn, pulls a .45 from his pocket, and in front of everybody shoots the project’s drug dealer at point-blank range. The reasons for this desperate burst of violence and the consequences that spring from it lie at the heart of Deacon King Kong, James McBride’s funny, moving novel and his first since his National Book Award-winning The Good Lord Bird. In Deacon King Kong, McBride brings to vivid life the people affected by the shooting: the victim, the African-American and Latinx residents who witnessed it, the white neighbors, the local cops assigned to investigate, the members of the Five Ends Baptist Church where Sportcoat was deacon, the neighborhood’s Italian mobsters, and Sportcoat himself. As the story deepens, it becomes clear that the lives of the characters―caught in the tumultuous swirl of 1960s New York―overlap in unexpected ways. When the truth does emerge, McBride shows us that not all secrets are meant to be hidden, that the best way to grow is to face change without fear, and that the seeds of love lie in hope and compassion. Bringing to these pages both his masterly storytelling skills and his abiding faith in humanity, James McBride has written a novel every bit as involving as The Good Lord Bird and as emotionally honest as The Color of Water. Told with insight and wit, Deacon King Kong demonstrates that love and faith live in all of us.

Opening Lines: Deacon Cuffy Lambkin of Five Ends Baptist Church became a walking dead man on a cloudy September afternoon in 1969. That’s the day the old deacon, known as Sportcoat to his friends, marched out to the plaza of the Causeway Housing Projects in South Brooklyn, stuck an ancient .45 Luger in the face of a nineteen-year-old drug dealer named Deems Clemens, and pulled the trigger.

Labels:

Fresh Ink,

Front Porch Books,

Larry Brown,

short stories

Thursday, October 5, 2017

The Eclectic Shelf: Eric Rickstad’s Library

Reader: Eric Rickstad

Location: Vermont

Collection size: No idea, a lot. Books everywhere.

The one book I’d back into a burning building to rescue: My 1992 Best American Short Stories

Favorite book from childhood: Danny, Champion of the World by Roald Dahl

My guilty pleasure: Best American Short Stories Collection

OK, I don’t really have a library. Not in the sense that I think of a library, that vast room with shelves from floor to ceiling, a place worthy of Colonel Mustard and his pipe wrench. But I do have a lot of bookshelves and cabinets.

This is what’s left of what was my Best American Short Stories and O’Henry Awards collection from 1974-2005. I lost so many editions to severe water damage, it kills me. I first read BASS in the early ’90s when in college. These stories opened up my mind to what was possible with words, precise language, and love of craft. Each was a gem that excited me to read more ravenously than ever, and a challenge to write my best. Joyce Carol Oates. Alice Munro. John Edgar Wideman. Harlan Ellison. Alice Adams. Rick Bass. Denis Johnson. And on and on and on. Who were these word conjurers of tales so strange and wondrous and singular? I devoured the stories, and I bought each subsequent edition in the years to come, along with the O’Henry collections. After reading the first copy I ever bought in 1992, I searched for past editions and bought them whenever I was in a used bookshop. Searching for and finding them was a feverish, earnest pursuit. Of course, they led me to the literary magazine world, and I gobbled up every copy of Cimarron Review, Tri-Quarterly, Boulevard, Prairie Schooner, Ploughshares, and dozens of others in the periodicals section of the University of Vermont’s Bailey Howe Library. There was no going back. The door was flung wide open.

When several boxes of my editions got ruined by water damage during a move, I felt gut punched. I could recall each story in my mind and where I was when I read it the first of many, many times, what it made me feel and think, and how it made me want to write. I remember I started Kate Braverman’s “Tall Tales from the Mekong Delta” on the front porch of my college apartment and had to finish it inside when a downpour struck out of the blue. I read Denis Johnson’s “Emergency” while waiting for my clothes to wash at the Laundromat. And I re-read it and re-read it and re-read it. What. Was. This? Magic.

When I lost all those editions in the mid 2000s, I could have easily searched for and bought online all the used editions I wanted, with a few clicks. I could have owned them all again, and more. I still could. But, no. It wouldn’t be the same, it wouldn’t be them: found in the back labyrinth of stacks in ancient used bookstores, dog-eared and tattered and stained, sentences and words and entire pages underlined during those moments of revelation upon my first read of them. So, I salvaged those books I could from the water damage. Luckily, among the books that were salvageable included the first one I bought in 1992. They occupy the top shelf where they belong, and once in a while I’ll take them down and be transported, not just back into the world of the stories, but to the time I first read that story. I don’t keep them in any order—as you can see, one is upside down. I read them, and I still take notes in them. They are there to be read.

I try to arrange books by author’s last name, alphabetically. It’s hopeless. As I buy more books, it would mean having to get rid of older books to accommodate new books, and I buy new books by the dozens. I gave up on shelves for a spell, and the new books just pile up. This shelf demonstrates an attempt at order, and the eclectic array on any given shelf. New books. Used books. Hardcovers and paperbacks. Fiction and nonfiction. Genre novels by John Sandford, Don Winslow and Nic Pizzolatto live among Carson Stroud, Carlos Ruiz Zafon, and Mia Siegert. Strewn among them are the nonfiction work On Fire by the late Larry Brown, Animals Make Us Human by Temple Grandin, Writing 21st Century Fiction by Donald Maass, and Under the Stars by Dan White, a history of camping in the U.S. Near one of Stephen King’s newer annual tomes and Donna Tartt’s latest addition in a decade, sit The Stories of Breece Pancake, a Wild Game Cookbook from the ’80s, and a favorite book of essays and photographs, with a foreword by the late Howard Frank Mosher, Deer Camp: Last Light in the Northeast Kingdom. Each shelf is its own mini collection of writers.

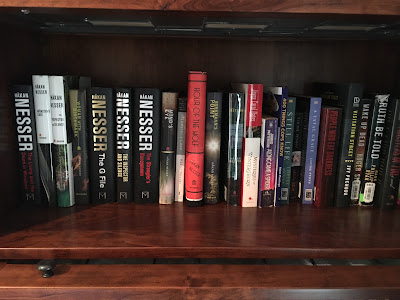

Sometimes, even in alphabetical order, a shelf will represent just a few authors in a specific genre, like this one, which is Hakan Nesser-centric, and mostly mystery/crime genre.

Other times, certain kings of the book world get their own shelf, or shelves.

There are shelves with just cookbooks, and just children’s books, rock n’ roll biographies, essays, philosophy, Judaism, hunting and fishing, and art. I keep building or buying shelves and giving away books I love to others, so they can enjoy them. I stack them at the bedside table, and the floor, and on the stairs, and I box them up and put boxes in the closet. I think I may well need a library.

Eric Rickstad is the New York Times, USA Today, and international bestselling author of The Canaan Crime Series: Lie in Wait, The Silent Girls, and his newest novel, The Names of Dead Girls. Dark, disturbing and compulsively readable psychological thrillers set in northern Vermont, the series is heralded as intelligent, profound, heartbreaking and mind shattering. His first novel Reap was a New York Times noteworthy novel. His fifth novel, What Remains of Her, is poised to be the most addictive and creepy read of the summer of 2018. Rickstad lives in his home state of Vermont.

My Library is an intimate look at personal book collections. Readers are encouraged to send high-resolution photos of their home libraries or bookshelves, along with a description of particular shelving challenges, quirks in sorting (alphabetically? by color?), number of books in the collection, and particular titles which are in the To-Be-Read pile. Email thequiveringpen@gmail.com for more information.

Tuesday, March 18, 2014

Trailer Park Tuesday: Joe (from the novel by Larry Brown)

Welcome to Trailer Park Tuesday, a showcase of new book trailers and, in a few cases, previews of book-related movies.

Larry Brown, the late, great chronicler of the South's darker corners, gets another big-screen treatment (after 2001's Big Bad Love). This time, Brown's 1991 novel Joe fills the screen with heavy drinking, domestic abuse and ornery men yelling, "The hell you lookin' at?" Nicolas Cage (who physically looks like Brown--perhaps intentionally?) plays the titular role of an alcoholic ex-con forester who hires a boy (Tye Sheridan, last seen with Matthew McConaughey in Mud) to work with him on his crew. When Joe discovers the 15-year-old boy is nothing but a punching bag for his alcoholic father, that ole ex-con rage starts to build inside him and you just know somebody's gonna get his ass whupped--or worse--before the end credits (a fact highlighted by a lawman coming across our anti-hero slumped against a wall and saying, "What have you done, Joe?"). All ingredients are in place for this to be a decent-to-good (possibly bordering on great) movie. I'm especially intrigued by the fact that David Gordon Green is the director. I'm a big fan of his films George Washington and Prince Avalanche and think his quiet, resonant style will serve Joe well. Now, will somebody please, please, please make a movie out of Larry Brown's final, posthumous novel, A Miracle of Catfish? I think it was one of his best.

A sad coda to this story: The actor cast as the abusive father did not live to see his work on screen. Two months after filming ended, Gary Poulter, a homeless man plucked from obscurity when Green cast him in the movie, was found dead....submerged in three feet of water after a night of heavy drinking near Austin’s Lady Bird Lake.

Thursday, May 10, 2012

It Came From Facebook: An interview with Lou Beach and his 420 Characters

In preparation for the Short Story Month party here at the blog, I sat down last week with Lou Beach's flash-fiction collection 420 Characters. It was a mind-blowing experience.

And when I say that, I mean Beach's book left my skull a smoking, hollowed-out crater, marveling at the possibilities of fiction. What he does on the page, within the straitjacket of 420 characters (including spaces and punctuation), leaves me in awe and admiration. This short story collection began as status updates on Facebook, back when Mr. Zuckerberg and Co. limited updates to the constraints of 420 characters. Beach began it on a whim, out of boredom with the social networking site, but it quickly turned into an enjoyable challenge to see just how well he could create miniature works of art. The author is, by trade, a visual artist and several of his collages are interspersed throughout the book, serving as a metaphor for the fragmentary nature of the fiction.

Beach's short-short stories may appear to be vignettes, Polaroid snapshots of scenes caught from the corner of an eye, but they have the emotional depth and heft of 300-page novels. His subject matter ranges across a huge spectrum of setting and style. In one story we read of a husband accusing his wife of messing with his tools ("How is that possible? Did you dip them in the bathtub like a tool fondue?"), and in the next we're on horseback with a cowboy in the Old West. Or we'll meet a skydiver whose chute fails to open and he crashes into a pigeon on his fatal plummet ("He felt the pigeon's heart beating against his own") and then later we're backstage with the Rolling Stones discussing women, drugs and clothes. And I haven't even mentioned the miniature person who lives inside the bright paisley shirt pocket of another man. Each of the one-page stories in 420 Characters gives readers a crumb, a sip, one nostril's-worth of breath, to an entire world which lies just beyond the door of the story. There is clear movement--physical and emotional--within each of these stories. As in the best short fiction, we "join the story in progress" and leave it just before a crucial denouement. Here's a good example of how well that works--this is the entire story as found on page 4 of the book:

I am exploring in the Bones, formations of caves interspersed with rock basins open to the sky. I hear a sound like a turbine as I exit a cave and approach the light ahead. I'm sure it's a waterfall. What I encounter is a massive beehive, honeycomb several stories high, millions of bees. I crouch down to avoid detection and notice a shift in the tone of the hive's collective drone. I turn around and see the bear.

Would it be fair to say Beach draws the lines in the coloring book and we fill in the spaces? Yes, that's accurate, I suppose, but it sounds a little like I'm reducing his artistry to mere scaffolding. Let me be clear: each of these tales is complete and satisfying in and of themselves. Do all of them succeed? Not always; there are some which come across as clever jokes or odd, failed experiments--but that's a very small percentage--maybe 3%--of the 169 stories in this book. Everything else is a red-carpet invitation to a fully-formed world, sprung whole and complete from Beach's rich imagination. Like this story found on page 42:

Huey "Pudge" Wilson, county sheriff, never met a man he didn't like to handcuff. What he knew about law wouldn't fill a thimble but what he knew about power would overflow the rain barrels between here and the river. Justice was just a tool of power, meted out in back rooms and measured in bruises and broken bones. When he was found slumped over in the cruiser, dead, Happy Hour took on new meaning.

|

| Click to enlarge |

Lou Beach was kind enough to answer a few questions via email. Here's our conversation:

420 Characters began its life on Facebook. Was this a deliberate plan on your part, or was it something that just happened one day while you were posting to social media? In other words, tell me the birth story of your flash-fiction collection.

It evolved from an amusement, a goof really, writing something fictional as a post, into an actual experiment where I'd write a piece every day. It was a challenge and on-the-job training, learning to write in front of an audience. The positive response to the posts definitely helped fuel my resolve to keep at it. ("Like"! ) I was excited by this new-found facility to squeeze a narrative into a limited format. It was the perfect storm too, a felicitous zeitgeist. It would not play today, given that the character limit has been so expanded on Facebook. Also, the film The Social Network was fresh in the public consciousness then so I think it was attractive to publishers. It also didn't hurt as well to have a website which was fashioned as a book. It made it palpable and included some celebrity readings that drew attention.

Are all the stories in the collection exactly 420 characters long? I've been too lazy to actually go in with a pencil tip and do a manual count by hand.

In spirit, yes. I believe there are a few that were massaged to include a few more characters to make the story clearer, but I was scrupulous to stay within the 420 limit on Facebook, which of course wouldn't post if I was over by even one character. There are some that are shorter...it seemed silly to pad out a story just to hit the magic number on the nose. It was more often a process of paring down, editing, than adding.

Your range is so varied and full of surprises. What triggered you to bring so many different characters to life (human characters, in this case)?

I have no idea. I operate on a purely intuitive level, listening to my dreams and snatches of dialogue from films or songs that trigger something that has the germ of a tale, then I get to work on it, pulling out the story. I have found that often reading some great author's work will compel me to hit the keyboard, not in imitation of their voice or plot or whatever, rather an excitement to create. Other writers inspire me very much, but so do film makers and painters and musicians, and chefs and athletes....Man, it's a world of wonders, isn't it?

Do you have a daily routine as a writer? I picture you carrying a notebook with you everywhere, jotting ideas and fragments as they pop into your head.

I wake up quite early, sometimes before five, and my mind is working on a story that I'd thought about before going to sleep. I lie there and move words around in my head, actually see it on the page. Then after breakfast I'll type it out and read it aloud, then revise and maybe think it stinks, then do something else, walk the dog, whatever, then come back to it and hope it's better, keep returning to it day after day until it rings true. That's speaking for what I'm doing today, which is writing longer pieces. The 420 stories were much more spontaneous and were often posted with no editing, sometimes to my chagrin.

What was the revision process like for 420 Characters?

Really not much. My editor at the time, Tom Bouman, was a fan of the work and except for a few push-and-pulls on what to include, we agreed on the format. He was good at choosing the sequence so that there was some kind of rhythm to the book, so that not all the western-themed ones were clumped together, for instance.

I only ask about revision because, as we all know, in fiction every word matters--from word choice to word placement. There is not a single syllable out of place in your flash fiction--entire worlds, pages of exposition, fully-realized characters are created in such short, tight spaces. Did you think about how readers' imaginations would start spinning and weaving secondary backstories to each of these pieces?

No, I didn't think about that, but for a long time there were a number of people who felt compelled to "finish" the stories or at least add on to them, a few at length, as if it were an interactive game. I didn't want to be a churl about it and ask them to stop--after all it's an open forum, but it was annoying at times. I had to not take myself too seriously...it was obviously something they enjoyed doing and ultimately it didn't really matter, didn't take anything away from the bigshot author.

How long did it take you to write these stories?

Sometimes a story would take 20 minutes to write, others an hour or two, others a day. It was probably two-and-a-half years from inception to completion of the book. After it came out and Facebook expanded the character limit, I was less interested in that concise form, though I would still try my hand at it. I wrote one the other day and was surprised at the difficulty I encountered. It's good practice though, like playing scales. I'm focusing now on longer pieces. They are still short, but I've managed to stretch out to several pages. As we say in Authors Anonymous, one sentence at a time.

I'm assuming there are others which never made it into the collection?

Oh yeah, there are hundreds.

At your website, you say you came to writing fiction as a surprising and "miraculous second act." In what way did the fiction grow out of your years as a visual artist?

I'd always entertained a fantasy of being a writer because I'd so often been astonished and intrigued by how a great writer can illuminate aspects of human nature, can use language in unsuspecting ways, can create worlds that are emotionally true. There are two aspects to my visual work. One is as an illustrator, primarily an editorial one, where my job is to find the kernel of the article and make a picture to go with it to draw the reader in, to advertise the article, basically. The other is my personal work, which is much closer in method to the writing. But in each aspect of the visual work, I create a narrative. The individual images within the composition are characters on the little stage set that is the page. And in the writing, I often "see" something from which I springboard into a tale. The other day I had a vision of a woman standing at the end of a dock on a lake. Where that image came from, I don't know, but I used it as the basis of a little story. Also, the making of a picture is an exercise in editing, removing elements and distilling the image, which is what I do in the writing.

The book really works well as a visual work of art--from the half-band dust jacket, to all the white space surrounding the stories, to the full-color collages included throughout. Did you have a hand in the design of the book? What feeling or message did you want to convey to readers about how fiction is bundled and packaged these days?

The cover was a recreation of the one I created for the book's website. The idea of the belly band came up in discussions with Martha Kennedy, an art director at Houghton Mifflin Harcourt and the page design was done by Melissa Lotfy. They are pros. I chose which collages to include. Everyone at Houghton was very supportive and excited about the book and made me feel that I was, indeed, a writer, when my own inclination was to think of myself as a lucky wanna-be. I love books, the physical feel and I wanted readers to have a satisfying tactile and visual experience in addition to the content, and I think we succeeded.

Are there any authors who specifically influenced your writing?

Oh man, I hate that question because there is always someone I feel I've left out or remember once the answers have been printed or posted. I admire George Saunders for his imagination and humanity, Elmore Leonard's mastery of dialogue and unfussiness, J. Robert Lennon, Jonathan Lethem, Pete Dexter, Carver (of course), Denis Johnson, Russell Banks, Alan Heathcock, the two Andre Dubuses, Scott Bradfield, Hemingway, Daniel Woodrell, Larry Brown, James Salter, Charles Baxter, Welty, Flannery O'Connor, Robert Stone and on and on...where do you stop? It seems with each book I pick up I find something that knocks me out, some passage, some turn of phrase, some insight into character that makes me want to be able to do THAT.

Do you have any favorite short stories or collections you typically recommend to readers?

Well, I don't typically make recommendations to readers, but any of the writers I just mentioned offer a wealth of treasures. In particular, I've been recommending Alan Heathcock's great Volt lately. It's a marvel.

Artwork: "The World of Men" courtesy of Lou Beach

Author photo by Issa Sharp

Tuesday, December 6, 2011

Moby-Dick in a Southern pond: A Miracle of Catfish by Larry Brown

When we think about how the notion of "work" is portrayed in fiction, we probably go immediately to the tried and true: policeman, fireman, butcher, baker, candlestick maker. Fueled by everything from the early readers of Richard Scarry to the latest Dilbert cartoon, labor in literature nearly always goes for the high-profile jobs. Every now and then a novel will come along that accurately portrays life for the majority of us who spend our days staring at the grey fabric of cubicle walls--books like Then We Came to the End by Joshua Ferris or Personal Days by Ed Park.

But who ever thinks of a catfish farmer?

Larry Brown did and the result is a wonderful portrait of the modern working man in A Miracle of Catfish, Brown's posthumous novel published in 2007.

A recent series on critics' "favorite book about work" at the National Book Critics Circle's Critical Mass blog started me thinking about the late great Larry Brown and his last novel. In A Miracle of Catfish, Tommy Bright is the down-on-his-luck owner of a fish-stocking business who, in the course of the novel, clandestinely slips a giant catfish named Ursula into 72-year-old Cortez Sharp's newly-dug pond. A Miracle of Catfish is filled with more than a dozen memorable characters, but I particularly enjoyed the scenes involving Tommy and his big red truck compartmentalized with tanks holding crappie, largemouth bass, bluegills, and bream.

Here is just one moment from Tommy's life when he's working late at his office out in the barn, agonizing over bills, balancing the books, and fretting over supplies needed to keep his fish alive:

Let us now praise the overlooked and overworked fish farmers of the world.

For more of the virtues of Brown's novel, here's a review I wrote for January Magazine shortly after the book came out:

Sometimes it's the unexpected loss of a great talent that fills us with regret and pangs us like a sore tooth. When a writer like Larry Brown dies of a sudden heart attack at age 53, we mourn his passing with a series of "what ifs" and "should haves." Yes, we knew he smoked like a chimney (ironic, considering he was a former firefighter) and that he probably drank as hard as the characters in his novels and short stories, but somehow we thought his pen would go on forever. Sadly, that was not to be.

When the heart attack felled him the day before Thanksgiving in 2004, Larry Brown left behind a devoted band of hardcore fans who compared him to a modern Faulkner, a Southern Raymond Carver, a force of nature unto himself. No one was better at describing the worn-out lives of lower-class Americans (except Carver himself). The Day the Words Died was a sad one for those who knew him personally and those who knew him only through books like Father and Son, Big Bad Love, Joe and Fay. However, he left behind more than mourners--he also left a nearly-finished sixth novel.

His publisher, Algonquin Books, has now delivered Brown's parting gift to our bookshelves. A Miracle of Catfish is not just Brown's last book, it's his best. Yes, it's raw and incomplete, but it's filled with so much pathos and longing and downright beautiful writing that you just know Brown was pouring everything he had into these pages.

In her editor's note, Algonquin's Shannon Ravenel says, "The first-draft manuscripts of his books were nearly always so polished stylistically that my job as editor mostly involved showing him the places I felt the novels would benefit from trimming. He was, as a novelist, likely to write more than he needed. Having honed his skills on the short-story form, he reveled in the wide spaces that novels offer."

Here, in A Miracle of Catfish, Brown runs wild and free in those wide open spaces and it's a joy to watch him cram as much as he can between the two covers. Ravenel tells us she trimmed this book down from a 710-page manuscript and here and there we do feel the loss of some material, but Ravenel has apparently not cut out any vital organs.

Set in rural Mississippi, A Miracle of Catfish sprawls across a year in the life of about a dozen characters, including 72-year-old Cortez Sharp who digs a pond and fills it with catfish, a down-on-his-luck fellow named Tommy who runs a fish-stocking business and who secretly slips a giant catfish into Cortez's pond, eight-year-old Jimmy who lives down the road from Cortez and whose sole happiness in life is riding his new go-kart, and Jimmy's daddy who knows he's "nothing but a fuckup, would never be anything but a fuckup, and never had been anything but that." Eventually, these lives--including Ursula, the Moby-Dick of catfish--intersect in ways great and small.

Most of the characters are stuck in the rut of blue-collar depression, both economic and mental. As he keeps hitting the snooze button to delay getting out of bed and going to his soul-grinding job at the factory, Jimmy's daddy (who is never known by anything but this label) laments: "He's going to have to fix his life somehow because it's not working the way it is. But what's he going to do? What's the first move he's going to make? What's he going to do today that's going to be different from yesterday?"

Jimmy's daddy is in a tailspin throughout the novel. Right down to the last time we see him, we're pretty certain he's not going to pull out of it. Bad luck, bad choices and ignorance cling to him like a stink he can't wash off his hands. He's responsible for a man's death at the factory (gruesomely, beautifully described by Brown), he experiments with and regrets adultery, he beats Jimmy and disappoints the boy at every turn, he drinks to excess, and his only entertainment seems to be sitting in his bedroom watching hunting videos with such a salivating passion you'd think they were soft-core porn (and yet, when he finally gets the chance to go on a real hunt with his work buddies, he proves to be an impotent and negligent failure).

It's his son, however, who draws most of our sympathy. He's a naive dreamer who always looks on the sunny side of life even as he's literally being beaten down. He's a simple, almost unbelievably ignorant boy, but we're drawn to him, rotten teeth and all. Late in the novel, Jimmy has an encounter with a horny German Shepherd that is at once both pitiful and hilarious. Brown carries the punchline through several chapters, but knows enough not to wear it thin. Young Jimmy is, after all, the closest we come to a main character and it's onto him that we project most of our pity. Here's a son who continues to bear a slavish devotion to his father even though the worthless fuckup is too lazy to fix the chain on the go-kart, never takes Jimmy to a Kenny Chesney concert as promised, and nearly kills the boy when he tosses him into a lake to teach him how to swim. Jimmy is a brave, sweet kid, even if he is unwise to the reproductive abilities of dogs.

There are some big scenes which stand out thanks to Brown's maestro method of delivering sharp, sudden violence (as when the factory worker is crushed to death) but it's the smaller moments which are the novel's pay-off. If this is a first draft, then Brown's skill with words is all that much more impressive. The beauty is in the details, whether he's describing the mechanics of a stove factory assembly line, or leaving us in awe of a monster catfish:

Brown takes pleasure in compiling the everyday minutiae of life. If you're the kind of reader who doesn't want to spend a whole chapter watching a man slowly filling a pond with buckets of fingerlings ("the water came flowing out in a wide tongue and the little catfish came swimming with it"), then this is probably not the book for you. The author takes his time, creating his huge mural with tiny brushstrokes.

Brown's world is one where you can pull up to a rural convenience store and find "a toddler standing in dirty underpants on the gravel out by the gas pumps eating cigarette butts." It's a place where a washed-up, burnt-out man lives in a "grassless mobile home that was no longer mobile, merely home" and eats "lighter-fluid-flavored hamburgers" washed down with a six-pack. It's country Brown knew like the veins on the back of his hand, a tucked-away part of the state where "dirt roads" led all through the woods on the other side of the railroad tracks and "little juke joints were scattered all up and down them, places where people gathered on weekend nights to listen to electric guitars and drink homemade whiskey and Budweiser." He makes it as authentic and pungent for the reader as the next-best thing to being there.

I get the feeling that, had Brown lived to see the novel to completion, this would have been a much longer book, a hefty culmination of all that his career had been building to--in short, a southern-fried masterpiece. As it stands, it comes just shy of achieving that status. Mind you, it is still great and wholly satisfying. Like a three-hour movie that's so absorbing you don't even notice your bladder pains until the end credits roll, A Miracle of Catfish keeps you glued to every one of its 455 pages. And yet, I often found myself wanting more. Some of the plot lines fray and fizzle and are outright abandoned, while others build to a climax that never really comes. I suppose much of that is due to Brown's untimely departure from life. Had the good Lord given him just one more year or even six months, I think it's safe to say we would be holding a work of genius in our hands.

As always, however, we cannot judge what could be, only what is. More than just a footnote in Brown's career, this is a story that sings and hums and whistles with a choir of voices, from throats burned by whiskey and cigarette smoke. To put it simply, I didn't want this novel to end. And I can say that about very few books these days.

The best way to describe Brown's writing is to take a page from his own book where he describes Cortez's dreams: "They had color and light and texture and dialogue. And mood. Lots of mood. Sometimes it was blue lights and a smoky bar. Sometimes it was wood smoke and a campfire." That's Larry Brown for you. Mood and texture, light and color, as real as pea gravel spitting out beneath your tires, as heartfelt as regret in a soured marriage. Goddamn, he'll be missed.

But who ever thinks of a catfish farmer?

Larry Brown did and the result is a wonderful portrait of the modern working man in A Miracle of Catfish, Brown's posthumous novel published in 2007.

A recent series on critics' "favorite book about work" at the National Book Critics Circle's Critical Mass blog started me thinking about the late great Larry Brown and his last novel. In A Miracle of Catfish, Tommy Bright is the down-on-his-luck owner of a fish-stocking business who, in the course of the novel, clandestinely slips a giant catfish named Ursula into 72-year-old Cortez Sharp's newly-dug pond. A Miracle of Catfish is filled with more than a dozen memorable characters, but I particularly enjoyed the scenes involving Tommy and his big red truck compartmentalized with tanks holding crappie, largemouth bass, bluegills, and bream.

Here is just one moment from Tommy's life when he's working late at his office out in the barn, agonizing over bills, balancing the books, and fretting over supplies needed to keep his fish alive:

He was too old to start over. He was fifty-seven. He ought to be thinking about retiring instead of all this bullshit. Hell. A man got old and tired. He got tired of the things that happened to him on his job. He'd lost count of the times he'd been finned by catfish, but he remembered the worst ones. The one that got him all the way through the thumb that day in Hot Springs. The one he stepped on that day in Batesville, Mississippi, and drove the fin up under his big toenail. He had very nearly shit on himself for real when that one happened. But hell. Everybody had something on their job to worry about. Firemen risked getting burned up. Ironworkers had to deal with the reality of falling to their deaths. Getting finned was a part of Tommy's life. You just tried to minimize it as much as you could. It helped to wear leather gloves.

Let us now praise the overlooked and overworked fish farmers of the world.

For more of the virtues of Brown's novel, here's a review I wrote for January Magazine shortly after the book came out:

Moby-Dick in a Southern Pond

Sometimes it's the unexpected loss of a great talent that fills us with regret and pangs us like a sore tooth. When a writer like Larry Brown dies of a sudden heart attack at age 53, we mourn his passing with a series of "what ifs" and "should haves." Yes, we knew he smoked like a chimney (ironic, considering he was a former firefighter) and that he probably drank as hard as the characters in his novels and short stories, but somehow we thought his pen would go on forever. Sadly, that was not to be.

When the heart attack felled him the day before Thanksgiving in 2004, Larry Brown left behind a devoted band of hardcore fans who compared him to a modern Faulkner, a Southern Raymond Carver, a force of nature unto himself. No one was better at describing the worn-out lives of lower-class Americans (except Carver himself). The Day the Words Died was a sad one for those who knew him personally and those who knew him only through books like Father and Son, Big Bad Love, Joe and Fay. However, he left behind more than mourners--he also left a nearly-finished sixth novel.

His publisher, Algonquin Books, has now delivered Brown's parting gift to our bookshelves. A Miracle of Catfish is not just Brown's last book, it's his best. Yes, it's raw and incomplete, but it's filled with so much pathos and longing and downright beautiful writing that you just know Brown was pouring everything he had into these pages.

In her editor's note, Algonquin's Shannon Ravenel says, "The first-draft manuscripts of his books were nearly always so polished stylistically that my job as editor mostly involved showing him the places I felt the novels would benefit from trimming. He was, as a novelist, likely to write more than he needed. Having honed his skills on the short-story form, he reveled in the wide spaces that novels offer."

Here, in A Miracle of Catfish, Brown runs wild and free in those wide open spaces and it's a joy to watch him cram as much as he can between the two covers. Ravenel tells us she trimmed this book down from a 710-page manuscript and here and there we do feel the loss of some material, but Ravenel has apparently not cut out any vital organs.

Set in rural Mississippi, A Miracle of Catfish sprawls across a year in the life of about a dozen characters, including 72-year-old Cortez Sharp who digs a pond and fills it with catfish, a down-on-his-luck fellow named Tommy who runs a fish-stocking business and who secretly slips a giant catfish into Cortez's pond, eight-year-old Jimmy who lives down the road from Cortez and whose sole happiness in life is riding his new go-kart, and Jimmy's daddy who knows he's "nothing but a fuckup, would never be anything but a fuckup, and never had been anything but that." Eventually, these lives--including Ursula, the Moby-Dick of catfish--intersect in ways great and small.

Most of the characters are stuck in the rut of blue-collar depression, both economic and mental. As he keeps hitting the snooze button to delay getting out of bed and going to his soul-grinding job at the factory, Jimmy's daddy (who is never known by anything but this label) laments: "He's going to have to fix his life somehow because it's not working the way it is. But what's he going to do? What's the first move he's going to make? What's he going to do today that's going to be different from yesterday?"

Jimmy's daddy is in a tailspin throughout the novel. Right down to the last time we see him, we're pretty certain he's not going to pull out of it. Bad luck, bad choices and ignorance cling to him like a stink he can't wash off his hands. He's responsible for a man's death at the factory (gruesomely, beautifully described by Brown), he experiments with and regrets adultery, he beats Jimmy and disappoints the boy at every turn, he drinks to excess, and his only entertainment seems to be sitting in his bedroom watching hunting videos with such a salivating passion you'd think they were soft-core porn (and yet, when he finally gets the chance to go on a real hunt with his work buddies, he proves to be an impotent and negligent failure).

It's his son, however, who draws most of our sympathy. He's a naive dreamer who always looks on the sunny side of life even as he's literally being beaten down. He's a simple, almost unbelievably ignorant boy, but we're drawn to him, rotten teeth and all. Late in the novel, Jimmy has an encounter with a horny German Shepherd that is at once both pitiful and hilarious. Brown carries the punchline through several chapters, but knows enough not to wear it thin. Young Jimmy is, after all, the closest we come to a main character and it's onto him that we project most of our pity. Here's a son who continues to bear a slavish devotion to his father even though the worthless fuckup is too lazy to fix the chain on the go-kart, never takes Jimmy to a Kenny Chesney concert as promised, and nearly kills the boy when he tosses him into a lake to teach him how to swim. Jimmy is a brave, sweet kid, even if he is unwise to the reproductive abilities of dogs.

There are some big scenes which stand out thanks to Brown's maestro method of delivering sharp, sudden violence (as when the factory worker is crushed to death) but it's the smaller moments which are the novel's pay-off. If this is a first draft, then Brown's skill with words is all that much more impressive. The beauty is in the details, whether he's describing the mechanics of a stove factory assembly line, or leaving us in awe of a monster catfish:

She was not a behemoth. She was a beauty. She was the nightmare fish of small boys and she came from the depths of sweaty dreams to suck them and their feeble cane poles from the bank or the boat dock to a soggy grave.

Brown takes pleasure in compiling the everyday minutiae of life. If you're the kind of reader who doesn't want to spend a whole chapter watching a man slowly filling a pond with buckets of fingerlings ("the water came flowing out in a wide tongue and the little catfish came swimming with it"), then this is probably not the book for you. The author takes his time, creating his huge mural with tiny brushstrokes.

Brown's world is one where you can pull up to a rural convenience store and find "a toddler standing in dirty underpants on the gravel out by the gas pumps eating cigarette butts." It's a place where a washed-up, burnt-out man lives in a "grassless mobile home that was no longer mobile, merely home" and eats "lighter-fluid-flavored hamburgers" washed down with a six-pack. It's country Brown knew like the veins on the back of his hand, a tucked-away part of the state where "dirt roads" led all through the woods on the other side of the railroad tracks and "little juke joints were scattered all up and down them, places where people gathered on weekend nights to listen to electric guitars and drink homemade whiskey and Budweiser." He makes it as authentic and pungent for the reader as the next-best thing to being there.

I get the feeling that, had Brown lived to see the novel to completion, this would have been a much longer book, a hefty culmination of all that his career had been building to--in short, a southern-fried masterpiece. As it stands, it comes just shy of achieving that status. Mind you, it is still great and wholly satisfying. Like a three-hour movie that's so absorbing you don't even notice your bladder pains until the end credits roll, A Miracle of Catfish keeps you glued to every one of its 455 pages. And yet, I often found myself wanting more. Some of the plot lines fray and fizzle and are outright abandoned, while others build to a climax that never really comes. I suppose much of that is due to Brown's untimely departure from life. Had the good Lord given him just one more year or even six months, I think it's safe to say we would be holding a work of genius in our hands.

As always, however, we cannot judge what could be, only what is. More than just a footnote in Brown's career, this is a story that sings and hums and whistles with a choir of voices, from throats burned by whiskey and cigarette smoke. To put it simply, I didn't want this novel to end. And I can say that about very few books these days.

The best way to describe Brown's writing is to take a page from his own book where he describes Cortez's dreams: "They had color and light and texture and dialogue. And mood. Lots of mood. Sometimes it was blue lights and a smoky bar. Sometimes it was wood smoke and a campfire." That's Larry Brown for you. Mood and texture, light and color, as real as pea gravel spitting out beneath your tires, as heartfelt as regret in a soured marriage. Goddamn, he'll be missed.

Thursday, September 1, 2011

Front Porch Books: September 2011 Edition

Front Porch Books is a monthly assessment of books--mainly advance review copies (aka "uncorrected proofs" and "galleys")--I've received from publishers, but also sprinkled with packages from Book Mooch and other sources. Because my dear friends, Mr. FedEx and Mr. UPS, deliver them with a doorbell-and-dash method of deposit, I call them my Front Porch Books. Note: most of these books won't be released for another 2-6 months; I'm just here to pique your interest and stock your wish lists. To see a larger version of the book covers, click on the thumbnails.

Crimes in Southern Indiana

by Frank Bill

(Farrar, Strauss and Giroux)

Few Fall releases have me as excited as Bill's debut collection of gnarly noir stories set in the Rustbelt of the Midwest. It's like there's a hundred-thousand bullets bumping through my bloodstream, unsettling me in a good way as I look forward to running my eyes across these pages. The stories probably aren't for everyone. If you like to read your fiction while sipping chamomile tea and listening to Josh Groban on your iPod dock, you probably want to keep away from Bill's rapists, drug dealers and no-good sonsabitches in wife-beater T-shirts. Just look at how he literally kicks down the door and comes at us with two loaded barrels right from the Opening Lines of the first story, "Hill Clan Cross":

The Night Strangers

by Chris Bohjalian

(Crown)

Just in time for Halloween, Bohjalian (Secrets of Eden, Skeletons at the Feast and The Double Bind) delivers a spooky ghost tale which begins, as all good hauntings do, in a dank basement behind a locked door:

The Angel Esmeralda: Nine Stories

by Don DeLillo

(Scribner)

Can this really be the first book of short stories the grand master of American postmodernism? Hard to believe, but true. After a 40-year career whose epic-novel highlights include Libra, White Noise and Underworld, DeLillo is finally bringing us a collection of compact fiction--nine stories bundled into 200 pages. I've had a hot-cold relationship with DeLillo (but mostly hot): loved Underworld, shrugged at The Body Artist, stopped just short of cartwheels for Libra. And yet, The Angel Esmeralda is another of my most-anticipated books of the Fall season (this always happens every September: a virtual book monsoon). The stories cover nearly the whole timeline of DeLillo's career, starting with "Creation" from 1979, so I'm expecting this will be an illuminating chart of one writer's progress.

The Sourtoe Cocktail Club

by Ron Franscell

(Globe Pequot Press)

The full title of Franscell's story of father-son bonding in Alaska is The Sourtoe Cocktail Club: The Yukon Odyssey of a Father and Son in Search of a Mummified Human Toe...and Everything Else. If that mummified human toe doesn't grab you, then I don't know what will--especially when you learn the human digit is an actual additive in a drink at a bar in Dawson City, Yukon. I'll stick with my little paper umbrella if it's all the same, thanks. Judging by these Opening Lines, Franscell's book looks like it's a deeply personal account of a tumultuous time in his life and should appeal to fans of memoirs like David Gilmour's The Film Club:

Sand Queen

by Helen Benedict

(Soho Press)

I'm understandably biased when I say I'm happy to see a rising tide of fiction about the Iraq War hitting bookshelves, but Benedict's novel about the unlikely relationship between a female American soldier and a female Iraqi medical student looks especially promising, judging from these Opening Lines:

The Dubious Salvation of Jack V

by Jacques Strauss

(Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

Here's another novel that opens with the equivalent of verbal fireworks. I focus a lot of my attention on Great Beginnings because they often make the difference between committing to a book or setting it aside for the proverbial "rainy day"--which, if I'm honest with myself, will never come. The Dubious Salvation of Jack V. centers around 11-year-old Jack Viljee, a white boy living in Johannesburg in 1989. Though, according to the Jacket Copy, Jack's world is "a rational simple place," apartheid shapes and squeezes the South Africa outside his front door and Jack's perception of that world is sharpened by the family's black maid Susie. "The noisy domesticity is upset by the arrival of Susie's fifteen-year-old son. Percy is bored, idle, and full of rage, and when he catches Jack in an indeliby shameful moment, Jack learns that the smallest act of revenge has consquences beyond his imagining." Oh yes, those Opening Lines. Here they are in all their attention-grabbing glory:

I Married You for Happiness

by Lily Tuck

(Atlantic Monthly Press)

Tuck's novel opens with the line "His hand is growing cold; still she holds it." Intrigued? Read on. Here's the Jacket Copy:

The Maid

by Kimberly Cutter

(Houghton Mifflin Harcourt)

One film that consistently makes my 10 Best Movies of All Time list is The Passion of Joan of Arc, a 1928 silent film starring Maria Falconetti. It's smartly filmed, emotionally wrenching, and features an unforgettable performance with Falconetti's transformative face looming large in the camera's frame. This is a long way of saying I've set the bar pretty high when it comes to narratives about Joan of Arc. I haven't had the chance to read Kimberly Cutter's novel, The Maid, but from the Opening Lines, it looks like it could be as rich and nourishing as those tears coursing down Falconetti's cheeks:

What It Is Like to Go to War

by Karl Marlantes

(Atlantic Monthly Press)

Like Joan of Arc, Marlantes knows a thing or two about leading soldiers into battle. A graduate of Yale and a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford, Marlantes suspended his studies to join the Marines in Vietnam. His bloody, fiery crucible of combat was documented in the novel Matterhorn. In my review elseweb, I had mixed feelings about Matterhorn, but I couldn't deny it "puts the reader in the thick of combat like few others I've read." Now, like Tim O'Brien's If I Die in a Combat Zone, Marlantes has given us the truth behind his Vietnam fiction. What It is Like to Go to War documents the author's experiences in Southwest Asia and opens the aperture wide to comment on the societal role of combat and its place in literature. Blurbworthiness: ''Karl Marlantes has written a staggeringly beautiful book on combat--what it feels like, what the consequences are, and above all, what society must do to understand it. In my eyes he has become the preeminent literary voice on war of our generation. He is a natural storyteller and a deeply profound thinker who not only illuminates war for civilians, but also offers a kind of spiritual guidance to veterans themselves. As this generation of warriors comes home, they will be enormously helped by what Marlantes has written--I'm sure he will literally save lives.'' (Sebastian Junger) Here are the Opening Lines to the first chapter ("Temple of Mars"):

Watergate

by Thomas Mallon

(Pantheon Books)

I've been a fan of Thomas Mallon's work from the day I read Henry and Clara, his smart, engaging novel about the Civil War officer who was stabbed on the night he joined Abraham Lincoln in that fateful box seat at Ford's Theater. Mallon approaches history like it was a half-filled canvas waiting to be painted with fiction. His other novels--including Dewey Defeats Truman, Two Moons, and Bandbox--each take a different slice of our history and give it a fresh, human perspective. Now Mallon enters the nondescript office building in downtown Washington on a summer evening in 1972 for his exploration of America's worst political scandal. I, for one, can't wait to find out what's on the missing eighteen-and-a-half minutes of tape (though we'll have to wait for February when Mallon's novel is released). Here's the Jacket Copy:

A Thousand Lives: The Untold Story of Hope, Deception, and Survival at Jonestown

by Julia Scheeres

(Free Press)

Here's another story which shared the headlines of the 1970s with Watergate. For anyone who was alive in 1978, the news of the mass suicide (murder) from the Jonestown religious compound in Guyana was unforgettably shocking. I was 15 at the time and, thanks to the graphic photos in TIME magazine, I still carry the image of the sun-bloated bodies sprawled around the vat of Kool-Aid. Nearly one thousand people (913, to be exact) fell under the sway of Jim Jones, the leader of the Peoples Temple, and "drank the Kool-Aid" as a matter of faith. Julia Scheeres (author of the memoir Jesus Land) goes inside the tragedy, based on her first-hand interviews with survivors and families and her access to the diaries, letters and audiotapes collected by the FBI after the jungle massacre. This is a book which both calls to me and repels me. I approach the carnage with hesitant, weak-muscled legs, knowing that what I see and read will be horrific. And yet, 913 ghosts insist I have no other choice.

Fiction Ruined My Family

by Jeanne Darst

(Riverhead Books)

All writers' families are the same; they're all unhappy in their own quirky ways. Jeanne Darst comes from a literary lineage of novelists, journalists and alcoholics which provides hilarious fodder for her memoir. Here's the Jacket Copy for Fiction Ruined My Family:

Men in the Making

by Bruce Machart

(Houghton Mifflin Harcourt)