Showing posts with label Shakespeare. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Shakespeare. Show all posts

Thursday, December 5, 2019

Front Porch Books: December 2019 edition

Front Porch Books is a monthly tally of new and forthcoming books—mainly advance review copies (aka “uncorrected proofs” and “galleys”)—I’ve received from publishers. Cover art and opening lines may change before the book is finally released. I should also mention that, in nearly every case, I haven’t had a chance to read these books, but they’re definitely going in the to-be-read pile.

Cargill Falls

by William Lychack

(Braddock Avenue Books)

Jacket Copy: There is good reason why William Lychack’s writing has been called “Precise, exhilarating, sometimes wonderfully funny and always beautiful” (Margot Livesey). In prose you can practically feel moving in your hands, Cargill Falls takes you through a series of unforgettable scenes that coalesce into an extended meditation on the meanings we give—or fail to give—certain moments in our lives. The story begins when an adult William Lychack, hearing of the suicide of a childhood friend, sets out to make peace with a single, long-departed winter’s day when the two boys find a gun in the woods. Taking place over the course of just a few hours, this simple existential fact gathers totemic force as it travels backwards and forwards in time through Lychack’s consciousness and opens onto the unfinished business in the lives of the boys, their friends, parents, teachers, and even the family dog. Cargill Falls is a moving conversation with the past that transports us into the mysteries of love and longing and, finally, life itself. Brimming with generosity and wisdom, this is a novel that reveals a writer at the top of his form.

Opening Lines: We once found a gun in the woods—true story—me and Brownie, two of us walking home from school one day, twelve years old, and there on the ground in the leaves was a pistol. Almost didn’t even notice. Almost passed completely by. Had to be the last thing we expected, gun all black and dull at our feet, Brownie almost kicking it aside like an empty bottle or little-kid toy.

But then we saw what it was for real and got those shit-eating grins on our faces. We looked back to make sure no one else was coming. Nothing but skinny trees and muddy trail in either direction. Not even a bird chirping that we could hear. We held our breath to listen, everything so quiet we were afraid to move, whole world teetering as if balanced on a point.

Blurbworthiness: “Cargill Falls is an immediate classic. At once essential and profound and hugely entertaining, the story of the two boys at the heart of this book, and the men they become, follows in the tradition of great coming of age stories like Stand by Me, and then twists and reinvents and does the tradition better, upending all that we know and expect. It’s rare to come across books like this. A writer hopes that once in his or her life he or she can write something so honest.” (Charles Bock, author of Beautiful Children )

Why It’s In My Stack: I’m a mega-fan of Lychack’s short story collection The Architect of Flowers, so this new short novel was an automatic add to the top of the To-Be-Read (TBR) stack that towers both physically (dead-tree books) and virtually (e-books) in my life. Any new Lychack book will roughly elbow other books aside, without apology. Now, if you’ll excuse me, I’ve got a ride to catch to Cargill Falls where I’ll be following two young boys into the woods on a particular winter’s day.

Shakespeare for Squirrels

by Christopher Moore

(William Morrow)

Jacket Copy: Shakespeare meets Dashiell Hammett in this wildly entertaining murder mystery from Christopher Moore—an uproarious, hardboiled take on the Bard’s most performed play, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, featuring Pocket, the hero of Fool and The Serpent of Venice, along with his sidekick, Drool, and pet monkey, Jeff. Set adrift by his pirate crew, Pocket of Dog Snogging washes up on the sun-bleached shores of Greece, where he hopes to dazzle the Duke with his comedic brilliance and become his trusted fool. But the island is in turmoil. Egeus, the Duke’s minister, is furious that his daughter Hermia is determined to marry Demetrius, instead of Lysander, the man he has chosen for her. The Duke decrees that if, by the time of the wedding, Hermia still refuses to marry Lysander, she shall be executed . . .or consigned to a nunnery. Pocket, being Pocket, cannot help but point out that this decree is complete bollocks, and that the Duke is an egregious weasel for having even suggested it. Irritated by the fool’s impudence, the Duke orders his death. With the Duke’s guards in pursuit, Pocket makes a daring escape. He soon stumbles into the wooded realm of the fairy king Oberon, who, as luck would have it, is short a fool. His jester Robin Goodfellow—the mischievous sprite better known as Puck—was found dead. Murdered. Oberon makes Pocket an offer he can’t refuse: he will make Pocket his fool and have his death sentence lifted if Pocket finds out who killed Robin Goodfellow. But as anyone who is even vaguely aware of the Bard’s most performed play ever will know, nearly every character has a motive for wanting the mischievous sprite dead. With too many suspects and too little time, Pocket must work his own kind of magic to find the truth, save his neck, and ensure that all ends well. A rollicking tale of love, magic, madness, and murder, Shakespeare for Squirrels is a Midsummer Night’s noir—a wicked and brilliantly funny good time conjured by the singular imagination of Christopher Moore.

Opening Lines: We’d been adrift for eight days when the ninny tried to eat the monkey.

Why It’s In My Stack: I’m a fool for Shakespeare, I dig hardboiled crime fiction, and I need to laugh. I’m gonna tell the rest of the world to Puck off while I burrow into Christopher Moore’s latest pulpy production.

The Bright Side Sanctuary for Animals

by Becky Mandelbaum

(Simon and Schuster)

Jacket Copy: The Bright Side Sanctuary for Animals is in trouble. It’s late 2016 when Ariel discovers that her mother Mona’s animal sanctuary in Western Kansas has not only been the target of anti-Semitic hate crimes—but that it’s also for sale, due to hidden financial ruin. Ariel, living a new life in progressive Lawrence, and estranged from her mother for six long years, knows she has to return to her childhood home—especially since her own past may have played a role in the attack on the sanctuary. Ariel expects tension, maybe even fury, but she doesn’t anticipate that her first love, a ranch hand named Gideon, will still be working at the Bright Side. Back in Lawrence, Ariel’s charming but hapless fiancé, Dex, grows paranoid about her sudden departure. After uncovering Mona’s address, he sets out to confront Ariel, but instead finds her grappling with the life she’s abandoned. Amid the reparations with her mother, it’s clear that Ariel is questioning the meaning of her life in Lawrence, and whether she belongs with Dex or with someone else, somewhere else. Acclaimed writer Pam Houston says that “Mandelbaum is wise beyond her years and twice as talented,” and The Bright Side Sanctuary for Animals poignantly explores the unique love and tension between mothers and daughters, and humans and animals alike. Perceptive and funny, moving and eloquent, and ultimately buoyant, Mandelbaum offers a panoramic view of family and forgiveness, and of the meaning of home. Her debut reminds us that love provides refuge, and underscores our similarities as human beings, no matter how alone or far apart we may feel.

Opening Lines: It was midnight in Kansas, and the bigots were awake.

Why It’s In My Stack: That first sentence!

In Our Midst

by Nancy Jensen

(Dzanc Books)

Jacket Copy: Drawing upon a long-suppressed episode in American history, when thousands of German immigrants were rounded up and interned following the attack on Pearl Harbor, In Our Midst tells the story of one family’s fight to cling to the ideals of freedom and opportunity that brought them to America. Nina and Otto Aust, along with their teenage sons, feel the foundation of their American lives crumbling when, in the middle of the annual St. Nikolas Day celebration in the Aust Family Restaurant, their most loyal customers, one after another, turn their faces away and leave without a word. The next morning, two FBI agents seize Nina by order of the president, and the restaurant is ransacked in a search for evidence of German collusion. Ripped from their sons and from each other, Nina and Otto are forced to weigh increasingly bitter choices to stay together and stay alive. Recalling a forgotten chapter in history, In Our Midst illuminates a nation gripped by suspicion, fear, and hatred strong enough to threaten all bonds of love―for friends, family, community, and country.

Opening Lines: Nina’s favorite moment was the hush, just before she pushed through the swinging door from the kitchen into the dining room of the restaurant, holding out her best Dresden platter, filled to its gold-laced edges with thin slices of fruitpocked Christollen, chocolate Lebkuchen, and hand-pressed Springerle in a dozen designs, fragrant with aniseed. Following close behind would be her husband Otto, bearing the large serving bowl brimming with Pfeffernusse, crisp and brown―each spicy nugget no larger than a hazelnut―ready to dip them up with a silver ladle and pour them into their guests’ cupped and eager hands. Next would come the boys, Kurt first, with two silver pitchers―one of hot strong coffee, the other of tea―and then Gerhard, carrying the porcelain chocolate pot, still the purest white and so abloom with flowers in pink, yellow, and blue that it seemed ever a promise of spring. Nina’s mother had passed it on to her in 1925, a farewell gift when she, Otto, and the boys―Kurt a wide-eyed three and Gerhard just learning to walk―had left Koblenz for the Port of Hamburg, bound for America.

Why It’s In My Stack: I am drawn by the rich description of that hot meal coming through the swinging door into the restaurant―my mouth waters at the very words―which is such a pleasant scene...and one about to be destroyed by prejudice and hate.

Butch Cassidy

by Charles Leerhsen

(Simon and Schuster)

Jacket Copy: For more than a century the life and death of Butch Cassidy have been the subject of legend, spawning a small industry of mythmakers and a major Hollywood film. But who was Butch Cassidy, really? Charles Leerhsen, bestselling author of Ty Cobb, sorts out facts from folklore and paints a brilliant portrait of the celebrated outlaw of the American West. Born into a Mormon family in Utah, Robert Leroy Parker grew up dirt poor and soon discovered that stealing horses and cattle was a fact of life in a world where small ranchers were being squeezed by banks, railroads, and cattle barons. Sometimes you got caught, sometimes you got lucky. A charismatic and more than capable cowboy—even ranch owners who knew he was a rustler said they would hire him again—he adopted the alias “Butch Cassidy,” and moved on to a new moneymaking endeavor: bank robbery. By all accounts, Butch was a smart and considerate thief, refusing to take anything from customers and insisting that no one be injured during his heists. His “Wild Bunch” gang specialized in clever getaways, stationing horses at various points along their escape route so they could outrun any posse. Eventually Butch and his gang graduated to train robberies, which were more lucrative. But the railroad owners hired the Pinkerton Agency, whose detectives pursued Butch and his gang relentlessly, until he and his then partner Harry Longabaugh (The Sundance Kid) fled to South America, where they replicated the cycle of ranching, rustling, and robbery until they met their end in Bolivia. In Butch Cassidy, Charles Leerhsen shares his fascination with how criminals such as Butch deftly maneuvered between honest work and thievery, battling the corporate interests that were exploiting the settlers, and showing us in vibrant prose the Old West as it really was, in all its promise and heartbreak.

Opening Lines: Start at the end, they say.

The last member of Butch Cassidy’s gang, the Wild Bunch, went into the ground in December 1961. Which means that someone who held the horses during an old-school Western train robbery, or had been otherwise involved with the kind of men who crouched behind boulders with six-guns in their hands and bandanas tied around their sunburnt faces, might have voted for John F. Kennedy (or Richard Nixon), seen the movie West Side Story or heard Del Shannon sing run-run-run-run-runaway—that is, if she hadn’t been rendered deaf years earlier during the blasting open of a Union Pacific express car safe. Her outlaw buddies were always a little heavy-handed with the dynamite.

Yes—she. The Wild Bunch, which some writers have called the biggest and most structurally complex criminal organization of the late nineteenth century, came down, in the end, to one little old lady sitting in a small, dark apartment in Memphis. Laura Bullion died in obscurity eight years before the movie Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, starring Paul Newman and Robert Redford, revitalized the almost-forgotten semilegend in which she had played a minor but authentic part.

Why It’s In My Stack: Like many of you, my depth of knowledge about Butch Cassidy is only as thick as a daguerrotype photo print and about as long as a two-hour movie. Leerhsen’s biography of the outlaw looks like a vibrant and entertaining way to go deeper.

The Best Poems of Jane Kenyon

by Jane Kenyon

(Graywolf Press)

Jacket Copy: Published twenty-five years after her untimely death, The Best Poems of Jane Kenyon presents the essential work of one of America’s most cherished poets―celebrated for her tenacity, spirit, and grace. In their inquisitive explorations and direct language, Jane Kenyon’s poems disclose a quiet certainty in the natural world and a lifelong dialogue with her faith and her questioning of it. As a crucial aspect of these beloved poems of companionship, she confronts her struggle with severe depression on its own stark terms. Selected by Kenyon’s husband, Donald Hall, just before his death in 2018, The Best Poems of Jane Kenyon collects work from across a life and career that will be, as she writes in one poem, “simply lasting.”

Opening Lines: (“From Room to Room”)

Here in this house, among photographs

of your ancestors, their hymnbooks and old

shoes...

I move from room to room,

a little dazed, like the fly. I watch it

bump against each window.

I am clumsy here, thrusting

slabs of maple into the stove.

Blurbworthiness: “The poems of Jane Kenyon are lodestars. I can think of no better way to navigate life than to keep her work close, as I have always done. It’s thrilling to now have this great parting gift from Donald Hall―his loving, intimate, discerning selection of the best of her poems.” (Dani Shapiro, author of Inheritance)

Why It’s In My Stack: Otherwise, Kenyon’s collection of “new and selected poems,” which was published shortly after her death in 1995, remains one of my absolute favorite collections by a poet, contemporary or otherwise. Like Dani Shapiro, I keep Kenyon and her lodestar words close to me and within easy reach. I don’t know how many of the “greatest hits” collected here will be new to me, but a return trip to her work is overdue.

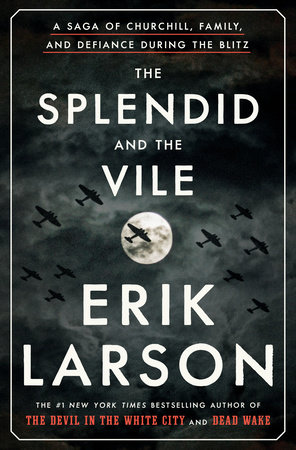

The Splendid and the Vile

by Erik Larson

(Crown)

Jacket Copy: On Winston Churchill’s first day as prime minister, Adolf Hitler invaded Holland and Belgium. Poland and Czechoslovakia had already fallen, and the Dunkirk evacuation was just two weeks away. For the next twelve months, Hitler would wage a relentless bombing campaign, killing 45,000 Britons. It was up to Churchill to hold his country together and persuade President Franklin Roosevelt that Britain was a worthy ally—and willing to fight to the end. In The Splendid and the Vile, Erik Larson (author of The Devil in the White City) shows, in cinematic detail, how Churchill taught the British people “the art of being fearless.” It is a story of political brinkmanship, but it’s also an intimate domestic drama, set against the backdrop of Churchill’s prime-ministerial country home, Chequers; his wartime retreat, Ditchley, where he and his entourage go when the moon is brightest and the bombing threat is highest; and of course 10 Downing Street in London. Drawing on diaries, original archival documents, and once-secret intelligence reports—some released only recently—Larson provides a new lens on London’s darkest year through the day-to-day experience of Churchill and his family: his wife, Clementine; their youngest daughter, Mary, who chafes against her parents’ wartime protectiveness; their son, Randolph, and his beautiful, unhappy wife, Pamela; Pamela’s illicit lover, a dashing American emissary; and the advisers in Churchill’s “Secret Circle,” to whom he turns in the hardest moments. The Splendid and the Vile takes readers out of today’s political dysfunction and back to a time of true leadership, when, in the face of unrelenting horror, Churchill’s eloquence, courage, and perseverance bound a country, and a family, together.

Opening Lines: No one had any doubt that the bombers would come. Defense planning began well before the war, though the planner had no specific threat in mind. Europe was Europe. If past experience was any sort of guide, a war could break out anywhere, anytime.

Why It’s In My Stack: Though I’ve yet to read any of Larson’s books (they’re all in my TBR pile!), his treatment of the Blitz looks like a good place to start. Bombs away and here we go!

Dressed All Wrong For This

by Francine Witte

(Blue Light Press)

Jacket Copy: Robert Olen Butler, author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning A Good Scent from a Strange Mountain, had this to say about the new collection of flash fiction by Francine Witte: “Dressed All Wrong For This is a splendid demonstration of the depth and range of the short-short story, an art form whose relevance and influence are rapidly growing in this digital age of compressed communication. Francine Witte brilliantly illuminates nuanced truths of the human condition in this collection, truths that could be expressed in no other way.”

Opening Lines: She became like a fish out of it. Dizzy. Always dizzy. And dry.

She would ready her arms for floating. Let them stretch out long and perpendicular. But nothing. Always nothing.

She thought of how she got here. Days and days of scorching sunlight. And other obvious signs. In fancy restaurants, when conversation turned to global warming, for instance, she said she would rather talk about film.

(From the opening story “When There Was No More Water”)

Blurbworthiness: “With Dressed All Wrong For This, Francine Witte has created an illuminated manuscript of life at a slant: where we encounter a woman who loses her “husband weight,” Suzo the clown and his many wives, a shadow that takes matters into its own hands. Rarely does one come across a story collection so astonishingly original, language so fresh, and surreal writing so rife with what is real to us all.” (Robert Scotellaro, author of Bad Motel)

Why It’s In My Stack: I’ll make this quick: Francine Witte writes with tectonic plates, pressing and squeezing words until they are compressed into gems. Her flash fiction short-short stories sparkle. I plan to pair Dressed All Wrong For This with Witte’s new poetry collection, The Theory of Flesh.

The Center of Everything

by Jamie Harrison

(Counterpoint)

Jacket Copy: For Polly, the small town of Livingston, Montana, is a magical ecosystem of extended family and raw, natural beauty governed by kinship networks that extend back generations. But the summer of 2002 finds Polly at a crossroads. A recent head injury has scattered her perception of the present, bringing to the surface events from thirty years ago and half a country away. A beloved friend goes missing on the Yellowstone River as Polly's relatives arrive for a reunion during the Fourth of July holiday, dredging up difficult memories for a family well acquainted with tragedy. Search parties comb the river as carefully as Polly combs her memories, and over the course of one fateful week, Polly arrives at a deeper understanding of herself and her larger-than-life family. Weaving together the past and the present, bounded by the brisk shores of Long Island Sound and the landscape of big-sky Montana, The Center of Everything examines with profound insight the nature of the human condition: the tribes we call family, the memories and touchstones that make up a life, and the loves and losses we must endure along the way.

Opening Lines: When Polly was a child, and thought like a child, the world was a fluid place. People came and went and never looked the same from month to month or year to year. They shifted bodies and voices—a family friend shaved a beard, a great aunt shriveled into illness, a doctor grew taller—and it would take time to find them, to recognize them.

Polly studied faces, she wondered, she undid the disguise. But sometimes people she loved disappeared entirely, curling off like smoke.

Why It’s In My Stack: I’ve been looking forward to holding Jamie Harrison’s next novel in my hands ever since the release of The Widow Nash two years ago. Based on Harrison’s other work, The Center of Everything is bound to delight and satisfy. Side note: I made my home in Livingston for a brief, windy spell in the mid-1980s, so I automatically gravitate toward any book set there.

The Impossible First

by Colin O’Brady

(Scribner)

Jacket Copy: Prior to December 2018, no individual had ever crossed the landmass of Antarctica alone, without support and completely human powered. Yet, Colin O’Brady was determined to do just that, even if, ten years earlier, there was doubt that he’d ever walk again normally. From the depths of a tragic accident, he fought his way back. In a quest to unlock his potential and discover what was possible, he went on to set three mountaineering world records before turning to this historic Antarctic challenge. O’Brady’s pursuit of a goal that had eluded many others was made even more intense by a head-to-head battle that emerged with British polar explorer Captain Louis Rudd—also striving to be “the first.” Enduring Antarctica’s sub-zero temperatures and pulling a sled that initially weighed 375 pounds—in complete isolation and through a succession of whiteouts, storms, and a series of near disasters—O’Brady persevered. Alone with his thoughts for nearly two months in the vastness of the frozen continent—gripped by fear and doubt—he reflected on his past, seeking courage and inspiration in the relationships and experiences that had shaped his life. Honest, deeply moving, filled with moments of vulnerability—and set against the backdrop of some of the most extreme environments on earth, from Mt. Everest to Antarctica—The Impossible First reveals how anyone can reject limits, overcome immense obstacles, and discover what matters most.

Opening Lines: I started thinking about my hands.

That was my first mistake.

After forty-eight days and more than 760 miles alone across Antarctica, the daily ache of my hands—cracked with cold, gripping my ski poles twelve hours a day—had become like a drumbeat, forming the rhythm of my existence.

Blurbworthiness: “Suspenseful, soul-searching, and at times metaphysical as O’Brady endures an endless sheet of white and ice...The book is a testament to the human soul and the amazing feats we can accomplish with training, willpower, and the singular resilience of the mind. You will learn from and be inspired by it.” (Buzz Bissinger, author of Friday Night Lights)

Why It’s In My Stack: Earlier this year, I traveled across the vast icy desert of Antarctica. I wasn’t alone: I was accompanied by Apsley Cherry-Garrard and his classic adventure book The Worst Journey in the World—a narrative of walking and sledding across the continent in the early 1910s with details so intense I braved frostbite to turn the pages. So, Antarctica has been on my mind a lot. O’Brady’s solo account is now perched near the icy peaks of my towering to-be-read mountain. I can’t wait to freeze again.

Afterlife

by Julia Alvarez

(Algonquin Books)

Jacket Copy: Antonia Vega, the immigrant writer at the center of Afterlife, has had the rug pulled out from under her. She has just retired from the college where she taught English when her beloved husband, Sam, suddenly dies. And then more jolts: her bighearted but unstable sister disappears, and Antonia returns home one evening to find a pregnant, undocumented teenager on her doorstep. Antonia has always sought direction in the literature she loves—lines from her favorite authors play in her head like a soundtrack—but now she finds that the world demands more of her than words. Afterlife, the first adult novel in almost fifteen years by the bestselling author of In the Time of the Butterflies and How the García Girls Lost Their Accents, is a compact, nimble, and sharply droll novel. Set in this political moment of tribalism and distrust, it asks: What do we owe those in crisis in our families, including—maybe especially—members of our human family? How do we live in a broken world without losing faith in one another or ourselves? And how do we stay true to those glorious souls we have lost?

Opening Lines: She is to meet him / a place they often choose for special occasions / to celebrate her retirement from the college / a favorite restaurant / and the new life awaiting her / a half-hour drive from their home / a mountain town / twenty if she speeds in the thirty-mile zone / Tonight it makes more sense / a midway point / to arrive separately / as she will be driving down from her doctor’s appointment / she gets there first / as he will be driving from home / he should have been there before her / she starts calling his cell / after waiting ten, twenty minutes / he doesn’t answer

Blurbworthiness: “Ravishing and heartfelt, Afterlife explores the complexities of familial devotion and tragedy against a backdrop of a world in crisis, and the ways in which we struggle to maintain hope, faith, compassion and love. This is Julia Alvarez at her best and most personal.” (Jonathan Santlofer, author of The Widower’s Notebook)

Why It’s In My Stack: I was blown away by the Prologue, whose opening lines I quoted above. It continues on in that fashion / fragments sliced by backslashes / for three pages / titled “Broken English” / the parts adding up to the whole. It reflects, in concrete form, the stuttering thoughts which swirl and dive-bomb our minds in times of grief. And it made me sit up and take notice that here was something fresh, something visceral, something that might make me cough up tears as the pages go on. (The rest of Afterlife is told in the “normal” way, sans backslash interruption.)

Labels:

Fresh Ink,

Front Porch Books,

poetry,

Shakespeare,

short stories,

William Lychack

Sunday, August 25, 2019

Sunday Sentence: Great Books by David Denby

Simply put, the best sentence(s) I’ve read this past week, presented out of context and without commentary.

NOTE: This week, while reading the “Shakespeare” chapter in David Denby’s Great Books, I couldn’t choose between sentences, so I am giving you a double-dose this week. You’re welcome.

My mother died the way she did everything, decisively and in great haste.

The play is about fierce, pre-Christian aristocrats, not American Jewish mothers. But Ida Denby was the Lear of my life.

Great Books by David Denby

Monday, February 11, 2019

My First Time: Stephen Evans

The First Time I Heard the Audience Laugh

I had heard audiences laugh before, of course. Most of my time in the theater was spent as a performer: a singer by choice, an actor (though not much of one) by necessity. But this was different.

In the early 1980s, I was playing Rosencrantz in Tom Stoppard’s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead to small bewildered houses in a theater outside Washington, DC. The play is a marvelous take on Hamlet as seen through the eyes of two minor characters, Hamlet’s two old pals.

During the run, I got an idea to write a play, a comedy about a playwright inspired by Shakespeare to write a play. I had never written a play before, but I didn’t know enough then to let that stop me. I managed over the next year or so to write the first act. But the second act stopped me and I did not finish the play.

About seven years later, I joined two of my oldest pals (also veterans of local theater) in starting a theater company. Our first show would be a fund-raiser, a musical review. Our second show would be my play—for which I now had to find a second act.

Production schedules wait for no man, or playwright. With lots of encouragement from my two friends and Shakespeare, I finally managed a second act to my play, now entitled The Ghost Writer. As opening night approached, it occurred to me that this was no longer just a personal intellectual challenge: could I write a play? An audience was actually going to answer that question for me.

I think of myself as a playwright who writes books. And I feel differently about publishing and producing. Publishing usually has a wider audience, and someone somewhere may let you know what they think. But it is distributed in time, and for me that lessens the impact. With a play, at least the first production, you are for better or worse usually right there sitting the audience. Everything is magnified, and very direct.

The lights went down on the audience of about 30 people, many of them friends. The curtain didn’t go up; it went sideways, which was suddenly how I expected the play to go. Then the lights came up onstage.

Sitting in the dark in the back row of the small theater, I was inundated with emotion. But more than anything—more than excited, more than terrified—I felt exposed. My thoughts, my words, my imagination were all going to be on display.

On opening night, the actress went about her opening business. No one got up and left. So far so good. Then the next actor entered. They exchanged a few lines. And then a miracle occurred.

Someone laughed.

Then more people started to laugh. They started to laugh together (this phenomenon of an audience coalescing to react in unison never ceases to fascinate me).

There were different kinds of laughter coming from that one small audience. I began to study them. There were the explosive laughs that erupted and subsided quickly, the wave laughs that started small and grew, the quantum laughs that jumped around the audience unpredictably, the lonely laughs from the one person (other than me) who thought it was funny, and the delayed exposure laugh, where it took a couple of beats for the audience to catch up before the laugh.

The audience, that blessed audience, continued laughing throughout the play. Not at the play. At the lines. The ones I had written.

I was hooked. From that moment on I knew that writing funny lines was what I wanted to do. Thoughtful funny lines. Funny lines laden with deep philosophic meaning that would change people’s lives.

Or just make them laugh.

That would be more than enough.

Stephen Evans is a playwright and the author of several books, including The Marriage of True Minds, A Transcendental Journey, Painting Sunsets, and The Island of Always. He lives in Maryland. Click here to visit his website.

My First Time is a regular feature in which writers talk about virgin experiences in their writing and publishing careers, ranging from their first rejection to the moment of holding their first published book in their hands. For information on how to contribute, contact David Abrams.

Wednesday, June 14, 2017

The Marriage of Books: Sarah Moriarty’s Library

Reader: Sarah Moriarty

Location: Brooklyn, NY

Collection size: About 700

The one book I'd run back into a burning building to rescue: Timing a Century: A History of the Waltham Watch Company by Charles Moore. Moore, my maternal grandfather, wrote business histories. He was a weekend farmer, a devout Quaker, a disciplinarian, and died when my mother was just sixteen.

Favorite book from childhood: Rebecca by Daphne Du Maurier or Seaward by Susan Cooper.

Guilty pleasure book: Be Here Now by Ram Dass or The Code of the Woosters by P.G. Wodehouse (This combination summarizes my personality).

The first time I lived with a boyfriend I knew the relationship was over when I started writing my name in all my books. I had internalized the advice from When Harry Met Sally. Harry tells his newly cohabitating friends to do so in order to avoid inevitably spending a fortune at the firm of “that’s mine, this is yours.” Apparently, the home library of a couple is a barometer for their relationship.

Now I have been married for eleven years to a man I’ve known for two decades, and our collections are seamlessly merged. Of course, there are some obvious distinctions between our books, but that is the nature of our very different tastes. His run to mythology, sci-fi, nonfiction, Modernism, and Buddhism. I am all fiction, creative nonfiction, YA, yoga, parenting, Victorians, Feminism, and Sufism. We overlap most in poetry, and here our collection has no sides or margins or borders or divisions. My Anne Sexton mingles with his e.e. cummings. We have gotten rid of duplicate copies of The Rattle Bag, Emily Dickinson, and Robert Lowell.

There are so many books: books for work, for self-improvement, for career development, for laughs, for cries, uppers, downers, laughers, screamers, gifted books, books written by friends, books about friends, books about books. We settled on an organizational scheme that combines two approaches: the books are separated into categories—poetry, fiction, religion, parenting, writing, education, art, mythology, feminism, young adult, and travel. Each category is then organized by color.

In doing so, I’ve noticed some trends. Often male authors’ titles are in blacks and dark blues, as are the classics and the anthologies. Female authors, like their suffragette sisters, are often in white, along with all the galleys and ARCs (this parallel is a whole other post in and of itself). Many contemporary titles come in vibrant reds and yellows and multiple stripes (Meg Wolizter!). Then there are the horrible primary colors of parenting books, the large spines and looping letters of religion and self-help titles in creams and sepias. There are, interestingly, very few greens (some Sagas, Norse, of course). Also very few pink.

But my library isn’t just a portrait of my relationship (or our society’s perceptions of color), but also of my career. Right after college I moved from Boston to New York and began my internship at Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. It was the final years of Roger Straus. The Corrections had come out the year before, and the paperback was released while I clipped articles from magazines for the publicity circulation. From my days in the mines of the publicity department of FSG, I absconded with some of my favorite books like Joseph Brodsky’s Nativity Poems, Jamaica Kincaid’s A Small Place, and MFK Fisher’s Serve It Forth.

When I moved on to W.W. Norton and Company, I started to bring home books in earnest to build a collection and keep a record of those I had worked on, even in my peripheral capacity as an editorial assistant. So much flap copy. So many press releases. This explains the slew of galleys on my shelves. While working at Norton I got to meet Vikram Seth, the author of one of my all time favorite books. I was charged with meeting him in the lobby and bringing him up to the 16th floor. In the elevator I rambled on about The Golden Gate. He replied, “that was a long time ago,” by which I think he meant it was not at all the book I ought to be rambling about. The elevator sped on until I realized we had passed our floor. In my fan girl blather I had forgotten to press the button.

Over time I became devoted to other Norton authors like Alice Fulton, Ann Hood, Audre Lorde, and Nick Flynn. Reading these authors convinced me that I needed to be on the other side of the desk and relieved of any public relations responsibilities.

Even the shelves of these great publishing houses paled in comparison to a place I acquired many of my books: the Saint Ann’s School book room. Yes, the pubescent Lena Dunhams of the world have some seriously good book stock. A school that focuses on classic books has all the heavy hitters I had ever meant to read in the bowels of their school basement between the boiler room and the woodshop. I wasn’t sure if I was dizzy and overheated from the joy of being surrounded by the great tomes of literature, or from the poorly ventilated boiler fumes. It was the kind of empty, silent place where probably a murderer was waiting for me around the stacks, but I didn’t care because I was already carrying more books than I could possibly bring home on the subway.

There I truly indulged my obsession with YA books and my devotion to classics: Huckleberry Finn, A Separate Peace, The Witch of Blackbird Pond, Boy, The Picture of Dorian Gray, Annie John, and oh so much Shakespeare. Every few weeks I brought home another armload under the guise of “research” and “context.” These books now form a substantial section of my teaching library.

My own YA section is sacrosanct, still devoted to those precious volumes I read when I was young, which hold all the joy of true escape: summer reading. These books—Watership Down; The Dark is Rising series; The Diamond in the Window; The Letter, the Witch, and the Ring; Jacob Have I Loved; The Book of Three series—fueled my obsession with imagery, narrative depth, and complex characters. These are not just books, but talismans. They have given me power and solace. I think that is what all books are meant to do.

Sarah Moriarty is the author of the new novel North Haven, and lives in Brooklyn with her husband, daughter, and various fauna.

My Library is an intimate look at personal book collections. Readers are encouraged to send high-resolution photos of their home libraries or bookshelves, along with a description of particular shelving challenges, quirks in sorting (alphabetically? by color?), number of books in the collection, and particular titles which are in the To-Be-Read pile. Email thequiveringpen@gmail.com for more information.

Thursday, February 2, 2017

Books for Dark Political Times: Michael Copperman’s Library

Reader: Michael Copperman

Location: Eugene, Oregon

Collection Size: Five hundred books

The one book I'd run back into a burning building to rescue: I Have a Dream: The March on Washington by Emma Gelders Sterne

Favorite book from childhood: James and the Giant Peach by Roald Dahl

Guilty pleasure book: Where the Sidewalk Ends by Shel Silverstein

My personal library is small. I live in a converted garage and rent out the rooms of my house, and I have boxes and boxes of books away in storage and in my office at the university. My awkward little secret is that I am often not much of a reader of contemporary fiction—I tend to read poetry as one consumes fuel, and keep those books thrown about the living room, where just now I am reading the collected work of Langston Hughes as if it might save my life. With everything else, I am immensely selective, and more likely when I am deep in work and process to reread something essential to me which speaks of mystery than I am to begin the latest NY Times bestseller. For instance, I have read Andre Dubus’s Dancing After Hours, five times, and would gladly begin it again. I have read the collected stories of Chekhov two or three times, and these days, every couple months I read his great short story “The Student,” an irreducible and indescribable little short about immanence, which in that story is the suggestion of imminence in the absence of wisdom, meaning, and God.

I keep the books which I am intending to read in a stack atop the rest on the right shelf on one side of the bed—books by friends or acquaintances, gifts, books which I feel I need to read or should have read. Sometimes books jump the queue that demand attention—on top now is a book by my great-grandmother, the writer Emma Gelders Sterne, I Have a Dream: The March on Washington which was published in 1965.

Recently I pulled that book from my father’s shelves of all Emma’s books as if drawn to it—to find a note from my father to me, his unborn son, five years before my birth, charging me with bearing on his grandmother’s legacy of writing, activism, compassion, and justice. As this is one of Emma’s books I did not read in my childhood, and speaks of a strength and solidarity and rising up I feel I may need to summon now, in these dark political times, I am excited to begin.

Atop the left shelf are books I’ve pulled from the shelves because I needed to read them as I work to complete an essay or my novel-in-progress—usually books which have been a long love of mine, or have particular resonance. So it is that Cesar Vallejo, translated by Roberty Bly and James Wright, sits atop that shelf. Vallejo, the music of my heart on big sad days of reckoning. So it is that Hamlet, has been set to the top, too, in this bitter winter, as has Willa Cather’s Five Stories, perhaps her least known work, but so large in lyric and retrospective force. I turn to these books as if to a holy book, a source—they do not directly instruct me, but their art and ethos are somewhere so near to what is in me as I work that they show me a way.

Michael Copperman is the author of Teacher, a memoir of the rural black public schools of the Mississippi Delta. He has taught writing to low-income, first-generation students of diverse background at the University of Oregon for the last decade. His prose has appeared in The Oxford American, The Sun, Creative Nonfiction, Salon, Gulf Coast, Guernica, Waxwing, and Copper Nickel, among other magazines, and has won awards and garnered fellowships from the Munster Literature Center, Breadloaf Writers’ Conference, Oregon Literary Arts, and the Oregon Arts Commission. Visit www.mikecopperman.com for more information about Michael and his book.

My Library is an intimate look at personal book collections. Readers are encouraged to send high-resolution photos of their home libraries or bookshelves, along with a description of particular shelving challenges, quirks in sorting (alphabetically? by color?), number of books in the collection, and particular titles which are in the To-Be-Read pile. Email thequiveringpen@gmail.com for more information.

Labels:

Andre Dubus,

Anton Chekhov,

My Library,

Shakespeare

Tuesday, January 17, 2017

Trailer Park Tuesday: Romeo and Juliet by David Hewson

Welcome to Trailer Park Tuesday, a showcase of new book trailers and, in a few cases, previews of book-related movies.

We’ve all heard the story: Boy meets Girl, they fall in love, their parents object, Boy and Girl get married anyway, Boy is banished from town, Girl pretends to kill herself in order to join Boy, Boy doesn’t get the memo and thinks Girl is really dead, Boy kills himself, Girl wakes up and finds her dead lover, Girl kills herself. The End. Unhappily Ever After. For those of you who’ve never read Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, I guess I just spoiled your reading (but, honestly, I don’t care; if you haven’t read the tragedy by this point in your life, then you should make like Ophelia in Hamlet and get thee to a nunnery). R & J is a time-tested, time-worn classic romantic tragedy that has become such a part of our popular culture, its original story and meaning often get lost in the superficial shortcuts we use to describe the young lovers. What we need is a fresh pen to help us see the story from a new perspective. Enter David Hewson with his vibrant and startling revision of the tale. Hewson’s Romeo and Juliet is only available as an audiobook, but it’s good enough to warrant getting a membership with Audible.com. There are many surprises in Hewson’s book (I promise not reveal the major ones); chief among them is Juliet’s character—a strong woman ahead of her time, a Renaissance feminist who does her best to stand up to her father and protest the arranged marriage with the rich, older Paris. There’s also a backstory for the kindly Friar Lawrence, whose brother turns out to be the pivotal and fateful Apothecary. All in all, Romeo and Juliet proves you can put new clothes on an old, tired body and have it look fresh as a daisy. It certainly helps to have a narrator like Richard Armitage. I was drawn to Romeo and Juliet in part due to the terrific reading Armitage gave David Copperfield earlier (and of course I’ve loved his on-screen performances in The Hobbit and North and South, among others). Though the characters’ voices are more Irish than Italian, I got used to the continental drift pretty quickly and fell headlong into the dialogue. When all is said and done, Armitage and Hewson combine forces to deliver a familiar story that sounds like we’re hearing it for the first time. Here’s a behind-the-scenes look at Armitage as he discusses why and how he took on this project:

Labels:

Charles Dickens,

reviews,

Shakespeare,

Trailer Tuesday

Monday, December 26, 2016

My First Time: Joseph Mills

My First Time is a regular feature in which writers talk about virgin experiences in their writing and publishing careers, ranging from their first rejection to the moment of holding their first published book in their hands. Today’s guest is Joseph Mills, author of the new poetry collection Exit, pursued by a bear. A faculty member at the University of North Carolina School of the Arts, Mills has published six volumes of poetry with Press 53, including Somewhere During the Spin Cycle, Sending Christmas Cards to Huck and Hamlet and Love and Other Collisions. His fifth collection, This Miraculous Turning, was awarded the North Carolina Roanoke-Chowan Award for Poetry. More information about his work is available at www.josephrobertmills.com.

My First Time Bathing with the Bard

After college, I travelled around in a Toyota pickup with a camper shell, and the only book I kept permanently in its back box was The Complete Works of William Shakespeare. It was a heavy blue-bound tome that I had bought at Powell’s Books in Chicago. I imagined reading it by campfires, delighting in the playwright’s timeless wisdom and his understanding of human relationships. I was, of course, also imagining myself as being the kind of person who read Shakespeare by a campfire.

But I wasn’t.

I never finished a single play in that collection.

There were physical reasons for this. Campfires don’t give off much light, and the type was tiny as the volume jammed together multiple columns on a page. Also, the book was too big. Literally. It was difficult to hold. It was a book to own rather than read.

There were other reasons as well. It turned out that I didn’t actually want to read Shakespeare. I wanted to be someone who had read Shakespeare. I wanted to be that erudite person who recognized phrases beyond “to be or not to be” and who got the reference when someone named their dog Portia or Shylock.

So I hauled the book around for a while then finally abandoned it out West, like those who jettisoned their possessions along the Oregon Trail.

Years later, on a New Year’s Day, I resolved again to be the person that I wanted to be (or thought I should be), and I decided to commit to reading a Shakespeare play a month. This time, I bought individual texts, ones that fit in the hand and the pocket. I had come to understand that part of the pleasure of reading is the physical experience of holding a book. It is a tactile relationship.

But I still wasn’t reading for pleasure. By that time I had read several Shakespeare plays at different points in my education (writing papers with arguments like “Hamlet can be read on many different levels” and “King Lear can be read on many different levels”) but, although I admired the work, or at least professed to, I didn’t emotionally respond to it. Instead, I started the project thinking it would be “good for me,” like going to the gym. In this mindset, I dutifully worked through a couple plays. Then, something unexpected happened.

One night, I took Henry VI, Part 2 into the bathroom. It is most famous for the line, “The first thing we do let’s kill all the lawyers.” In high school, I bought a coffee cup with that quotation for a friend who was pre-law. (Thinking back that was a jerk gift. Sorry, Denny.) As I read the play in the bath, Jack Cade, the Irish rebel, walks on stage holding two heads. He makes them kiss, separates them, then says he will ride through the streets “and at every corner have them kiss.” I laughed out loud at the audacity of this passage. It was dark. It was funny. At that moment, Shakespeare’s work opened to me in a way that it hadn’t before. I hadn’t responded to the “comedies” and at what I thought I was supposed to find amusing or witty. The archaic sex “jokes” often took too much work to figure out; by the time I realized what was happening, they weren’t funny. But this, this was a sardonic humor that I understood.

It was as if suddenly I had become attuned to how to read some of the plays. For example, the morning after Macbeth and Lady Macbeth have killed King Duncan, people arrive at the castle and emphasize how “unruly” the past night had been. One character notes that chimneys blew down, screams were in the air, birds were clamoring, and “some say the Earth/was feverous and did shake.” To this, Macbeth responds only, “Twas a rough night.” That is funny. Sly and ironic and dark and self-knowing.

I finished Henry VI, Part 2 in the bath. This, for me, is an unofficial mark of a good book. The cold water test. I discovered the novels of Dawn Powell when I took a bath with Angels on Toast and stayed there for hours.

So although I initially encountered Shakespeare in high school and had read various plays over the years, “my first time” truly responding to him was in a tub laughing at a dark dark scene. I don’t think it’s coincidental that it happened there. I had to strip away expectations of what Shakespeare’s work should be or who I should be while reading it. In a sense, I had to become a naked reader. So, it probably was just as well that I wasn’t by a fire.

Thursday, November 3, 2016

All the Hungry Possibilities: Elizabeth J. Church’s Library

Reader: Elizabeth J. Church

Location: Los Alamos, NM

Collection Size: est. 6,000

The one book I’d run back into a burning building to rescue: This question violates the Eighth Amendment prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment. But okay, since you INSIST–my Riverside Shakespeare (and it weighs a ton).

Favorite book from childhood: Beautiful Joe by Marshall Saunders

Guilty pleasure book: Valley of the Dolls by Jacqueline Susann

Each time I’ve moved over the years, friends have accused me of mislabeling boxes. “No one can have this many books!” they’ve moaned. But there’s been no deception on my part. I really do own–and love and adore and need–that many books. This obsession, this indefatigable love, will preclude my ever taking off in a tear-drop trailer–unless I lug a second trailer full of books in my wake.

It began with my mother reading to me and my brothers from The Illustrated Treasury of Children’s Literature (1955). We memorized traditional verses about Little Miss Muffet and Diddle Diddle Dumpling, and we played patty-cake while chanting. The book was so loved that my mother in later years had to repair the binding. Ever a product of the Great Depression, she used what was at hand: duct tape.

I progressed to Hans Christian Andersen and the Brothers Grimm. I bought my own Nancy Drew books with my allowance (the books cost $1.00, but with an allowance of 25 cents per week, 10 cents of which had to go to a church offering, that took a long while to earn). My mother had grown up poor, unable to own her own books, but from my father’s childhood library I had glorious old copies of Freckles, A Girl of the Limberlost, several volumes of the Bobbsey Twins, and Black Beauty.

I devoured all the classics: Jane Eyre, Wuthering Heights, and the exquisite Mr. Dickens. I had to be told to go outside and play, to “go get some fresh air”–which meant I hid a book beneath my clothing, went outside, and read.

In high school, I was fortunate enough to have an English teacher who saw my hunger and set about to feed it with consistently nutritional meals. She designed an individual study course for me (then an unheard of approach to teaching). She called it “Great Books.” I was allowed to suggest titles, and she filled in the gaps with F. Scott Fitzgerald, Hemingway, and T. S. Eliot, among others. The two of us would then sit and discuss what I’d read. In retrospect, I think she might have enjoyed our conversations nearly as much as I did, as I recognize what a delight it is to find a young mind eager for books and ideas, someone who is discovering the power, the beauty of words, and the compelling nature of shared stories.

In undergraduate school, I majored in English and minored in French–and I read (slowly, often stumbling) Flaubert, Gide, Zola, Balzac and others in their original French. I found Faulkner, whose darkness spoke most directly to me. Joan Didion, The Killer Angels by Michael Shaara, and All the King’s Men by Robert Penn Warren. I shouted with joy while reading the poetry of Shakespeare, and I put on the highest pedestal Milton’s Paradise Lost. With one generous professor, I sat cross-legged on his office floor and along with him nearly wept over the full-blown roses of Keats, Shelley, and Byron.

Over the ensuing years, all of those volumes have accompanied me from apartment to apartment, home to home. I always dreamt of having a physical, personal library like the ones in Jane Eyre or other such novels. Finally, I gave myself that, and I had bookshelves built to surround my bed. I put fiction around my head, non-fiction facing me on the opposite wall.

It was sheer heaven to see the tentative morning light bless the volumes, and at night to think of all the books I’d consumed, as well as all of the hungry possibilities that still awaited me.

I practiced law for many decades, but in the wake of my husband’s premature death I chose to walk away and instead do what I’d always wanted to do: write books of my own. To do that, I had to give up my home–and that precious library–for a smaller, more affordable house. “Smaller” meant that I also had to give up books. I cut my collection in less than half–an excruciating debridement that at times sliced into bone, even marrow. And yet, once I moved into my cozy new home, I discovered I had to give up even more books just to be able to fit the rest of my life into the house, which was half the size of my previous home.

Two years later, I find myself hunting for books that I thought I’d kept but instead reluctantly let leave me–and I am gradually repurchasing those that I realize I simply don’t want to be without. The library is still divided into fiction and non-fiction. And yes, there are towers of to-be-read books (always a reassuring sight to this hoarder). Both sets of shelves include sections on Vietnam, which is an abiding fascination to me. They are the men of my generation, the men who have populated my life and whom I’ve loved: Robert Olen Butler’s A Good Scent from a Strange Mountain and the unsurpassed The Things They Carried by Tim O’Brien. Most harrowing–and excruciatingly intimate–is Dear America: Letters Home from Vietnam, a compilation of letters written by soldiers and POWs.

For the most part, my library is arranged by “Where will one of this width and size fit?” But I also have shelves that represent the Civil War, Transcendentalism, psychology and philosophy, and my current Olympian Gods of Fiction–such as Colm Toibin and Colum McCann, Faulkner, Fitzgerald, Jean Rhys, D. H. Lawrence, and Michael Cox.

With the publication of my novel, The Atomic Weight of Love, I made one change to my library. I was able, at long last, to fulfill the most constant wish of my life: that I could see my name on a binding and place it next to whomever I chose. I’ll let you find where Atomic resides this week (she moves about in uncanny ways).

Elizabeth J. Church’s debut novel, The Atomic Weight of Love, was a long time coming–it was published when she’d reached age sixty. Atomic was recently released in the United Kingdom, and it comes out in paperback from Algonquin Books in the U.S. in March 2017. Her second novel, Map of Venus, is slated for publication in the spring of 2018. Elizabeth left the practice of law to pursue her lifelong dream of writing, and she has never–for a moment–regretted that decision.

My Library is an intimate look at personal book collections. Readers are encouraged to send high-resolution photos of their home libraries or bookshelves, along with a description of particular shelving challenges, quirks in sorting (alphabetically? by color?), number of books in the collection, and particular titles which are in the To-Be-Read pile. Email thequiveringpen@gmail.com for more information.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)