Front Porch Books is a monthly tally of new and forthcoming books—mainly advance review copies (aka “uncorrected proofs” and “galleys”)—I’ve received from publishers. Cover art and opening lines may change before the book is finally released. I should also mention that, in nearly every case, I haven’t had a chance to read these books, but they’re definitely going in the to-be-read pile.

Cargill Falls

by William Lychack

(Braddock Avenue Books)

Jacket Copy: There is good reason why William Lychack’s writing has been called “Precise, exhilarating, sometimes wonderfully funny and always beautiful” (Margot Livesey). In prose you can practically feel moving in your hands,

Cargill Falls takes you through a series of unforgettable scenes that coalesce into an extended meditation on the meanings we give—or fail to give—certain moments in our lives. The story begins when an adult William Lychack, hearing of the suicide of a childhood friend, sets out to make peace with a single, long-departed winter’s day when the two boys find a gun in the woods. Taking place over the course of just a few hours, this simple existential fact gathers totemic force as it travels backwards and forwards in time through Lychack’s consciousness and opens onto the unfinished business in the lives of the boys, their friends, parents, teachers, and even the family dog.

Cargill Falls is a moving conversation with the past that transports us into the mysteries of love and longing and, finally, life itself. Brimming with generosity and wisdom, this is a novel that reveals a writer at the top of his form.

Opening Lines: We once found a gun in the woods—true story—me and Brownie, two of us walking home from school one day, twelve years old, and there on the ground in the leaves was a pistol. Almost didn’t even notice. Almost passed completely by. Had to be the last thing we expected, gun all black and dull at our feet, Brownie almost kicking it aside like an empty bottle or little-kid toy.

But then we saw what it was for real and got those shit-eating grins on our faces. We looked back to make sure no one else was coming. Nothing but skinny trees and muddy trail in either direction. Not even a bird chirping that we could hear. We held our breath to listen, everything so quiet we were afraid to move, whole world teetering as if balanced on a point.

Blurbworthiness: “

Cargill Falls is an immediate classic. At once essential and profound and hugely entertaining, the story of the two boys at the heart of this book, and the men they become, follows in the tradition of great coming of age stories like

Stand by Me, and then twists and reinvents and does the tradition better, upending all that we know and expect. It’s rare to come across books like this. A writer hopes that once in his or her life he or she can write something so honest.” (Charles Bock, author of

Beautiful Children )

Why It’s In My Stack: I’m a mega-fan of Lychack’s short story collection

The Architect of Flowers, so this new short novel was an automatic add to the top of the To-Be-Read (TBR) stack that towers both physically (dead-tree books) and virtually (e-books) in my life. Any new Lychack book will roughly elbow other books aside, without apology. Now, if you’ll excuse me, I’ve got a ride to catch to Cargill Falls where I’ll be following two young boys into the woods on a particular winter’s day.

Shakespeare for Squirrels

by Christopher Moore

(William Morrow)

Jacket Copy: Shakespeare meets Dashiell Hammett in this wildly entertaining murder mystery from Christopher Moore—an uproarious, hardboiled take on the Bard’s most performed play,

A Midsummer Night’s Dream, featuring Pocket, the hero of

Fool and

The Serpent of Venice, along with his sidekick, Drool, and pet monkey, Jeff. Set adrift by his pirate crew, Pocket of Dog Snogging washes up on the sun-bleached shores of Greece, where he hopes to dazzle the Duke with his comedic brilliance and become his trusted fool. But the island is in turmoil. Egeus, the Duke’s minister, is furious that his daughter Hermia is determined to marry Demetrius, instead of Lysander, the man he has chosen for her. The Duke decrees that if, by the time of the wedding, Hermia still refuses to marry Lysander, she shall be executed . . .or consigned to a nunnery. Pocket, being Pocket, cannot help but point out that this decree is complete bollocks, and that the Duke is an egregious weasel for having even suggested it. Irritated by the fool’s impudence, the Duke orders his death. With the Duke’s guards in pursuit, Pocket makes a daring escape. He soon stumbles into the wooded realm of the fairy king Oberon, who, as luck would have it,

is short a fool. His jester Robin Goodfellow—the mischievous sprite better known as Puck—was found dead. Murdered. Oberon makes Pocket an offer he can’t refuse: he will make Pocket his fool and have his death sentence lifted if Pocket finds out who killed Robin Goodfellow. But as anyone who is even vaguely aware of the Bard’s most performed play ever will know, nearly every character has a motive for wanting the mischievous sprite dead. With too many suspects and too little time, Pocket must work his own kind of magic to find the truth, save his neck, and ensure that all ends well. A rollicking tale of love, magic, madness, and murder,

Shakespeare for Squirrels is a Midsummer Night’s noir—a wicked and brilliantly funny good time conjured by the singular imagination of Christopher Moore.

Opening Lines: We’d been adrift for eight days when the ninny tried to eat the monkey.

Why It’s In My Stack: I’m a fool for Shakespeare, I dig hardboiled crime fiction, and I need to laugh. I’m gonna tell the rest of the world to Puck off while I burrow into Christopher Moore’s latest pulpy production.

The Bright Side Sanctuary for Animals

by Becky Mandelbaum

(Simon and Schuster)

Jacket Copy: The Bright Side Sanctuary for Animals is in trouble. It’s late 2016 when Ariel discovers that her mother Mona’s animal sanctuary in Western Kansas has not only been the target of anti-Semitic hate crimes—but that it’s also for sale, due to hidden financial ruin. Ariel, living a new life in progressive Lawrence, and estranged from her mother for six long years, knows she has to return to her childhood home—especially since her own past may have played a role in the attack on the sanctuary. Ariel expects tension, maybe even fury, but she doesn’t anticipate that her first love, a ranch hand named Gideon, will still be working at the Bright Side. Back in Lawrence, Ariel’s charming but hapless fiancé, Dex, grows paranoid about her sudden departure. After uncovering Mona’s address, he sets out to confront Ariel, but instead finds her grappling with the life she’s abandoned. Amid the reparations with her mother, it’s clear that Ariel is questioning the meaning of her life in Lawrence, and whether she belongs with Dex or with someone else, somewhere else. Acclaimed writer Pam Houston says that “Mandelbaum is wise beyond her years and twice as talented,” and The Bright Side Sanctuary for Animals poignantly explores the unique love and tension between mothers and daughters, and humans and animals alike. Perceptive and funny, moving and eloquent, and ultimately buoyant, Mandelbaum offers a panoramic view of family and forgiveness, and of the meaning of home. Her debut reminds us that love provides refuge, and underscores our similarities as human beings, no matter how alone or far apart we may feel.

Opening Lines: It was midnight in Kansas, and the bigots were awake.

Why It’s In My Stack: That first sentence!

In Our Midst

by Nancy Jensen

(Dzanc Books)

Jacket Copy: Drawing upon a long-suppressed episode in American history, when thousands of German immigrants were rounded up and interned following the attack on Pearl Harbor,

In Our Midst tells the story of one family’s fight to cling to the ideals of freedom and opportunity that brought them to America. Nina and Otto Aust, along with their teenage sons, feel the foundation of their American lives crumbling when, in the middle of the annual St. Nikolas Day celebration in the Aust Family Restaurant, their most loyal customers, one after another, turn their faces away and leave without a word. The next morning, two FBI agents seize Nina by order of the president, and the restaurant is ransacked in a search for evidence of German collusion. Ripped from their sons and from each other, Nina and Otto are forced to weigh increasingly bitter choices to stay together and stay alive. Recalling a forgotten chapter in history,

In Our Midst illuminates a nation gripped by suspicion, fear, and hatred strong enough to threaten all bonds of love―for friends, family, community, and country.

Opening Lines: Nina’s favorite moment was the hush, just before she pushed through the swinging door from the kitchen into the dining room of the restaurant, holding out her best Dresden platter, filled to its gold-laced edges with thin slices of fruitpocked Christollen, chocolate Lebkuchen, and hand-pressed Springerle in a dozen designs, fragrant with aniseed. Following close behind would be her husband Otto, bearing the large serving bowl brimming with Pfeffernusse, crisp and brown―each spicy nugget no larger than a hazelnut―ready to dip them up with a silver ladle and pour them into their guests’ cupped and eager hands. Next would come the boys, Kurt first, with two silver pitchers―one of hot strong coffee, the other of tea―and then Gerhard, carrying the porcelain chocolate pot, still the purest white and so abloom with flowers in pink, yellow, and blue that it seemed ever a promise of spring. Nina’s mother had passed it on to her in 1925, a farewell gift when she, Otto, and the boys―Kurt a wide-eyed three and Gerhard just learning to walk―had left Koblenz for the Port of Hamburg, bound for America.

Why It’s In My Stack: I am drawn by the rich description of that hot meal coming through the swinging door into the restaurant―my mouth waters at the very words―which is such a pleasant scene...and one about to be destroyed by prejudice and hate.

Butch Cassidy

by Charles Leerhsen

(Simon and Schuster)

Jacket Copy: For more than a century the life and death of Butch Cassidy have been the subject of legend, spawning a small industry of mythmakers and a major Hollywood film. But who was Butch Cassidy, really? Charles Leerhsen, bestselling author of

Ty Cobb, sorts out facts from folklore and paints a brilliant portrait of the celebrated outlaw of the American West. Born into a Mormon family in Utah, Robert Leroy Parker grew up dirt poor and soon discovered that stealing horses and cattle was a fact of life in a world where small ranchers were being squeezed by banks, railroads, and cattle barons. Sometimes you got caught, sometimes you got lucky. A charismatic and more than capable cowboy—even ranch owners who knew he was a rustler said they would hire him again—he adopted the alias “Butch Cassidy,” and moved on to a new moneymaking endeavor: bank robbery. By all accounts, Butch was a smart and considerate thief, refusing to take anything from customers and insisting that no one be injured during his heists. His “Wild Bunch” gang specialized in clever getaways, stationing horses at various points along their escape route so they could outrun any posse. Eventually Butch and his gang graduated to train robberies, which were more lucrative. But the railroad owners hired the Pinkerton Agency, whose detectives pursued Butch and his gang relentlessly, until he and his then partner Harry Longabaugh (The Sundance Kid) fled to South America, where they replicated the cycle of ranching, rustling, and robbery until they met their end in Bolivia. In

Butch Cassidy, Charles Leerhsen shares his fascination with how criminals such as Butch deftly maneuvered between honest work and thievery, battling the corporate interests that were exploiting the settlers, and showing us in vibrant prose the Old West as it really was, in all its promise and heartbreak.

Opening Lines: Start at the end, they say.

The last member of Butch Cassidy’s gang, the Wild Bunch, went into the ground in December 1961. Which means that someone who held the horses during an old-school Western train robbery, or had been otherwise involved with the kind of men who crouched behind boulders with six-guns in their hands and bandanas tied around their sunburnt faces, might have voted for John F. Kennedy (or Richard Nixon), seen the movie

West Side Story or heard Del Shannon sing run-run-run-run-runaway—that is, if she hadn’t been rendered deaf years earlier during the blasting open of a Union Pacific express car safe. Her outlaw buddies were always a little heavy-handed with the dynamite.

Yes—she. The Wild Bunch, which some writers have called the biggest and most structurally complex criminal organization of the late nineteenth century, came down, in the end, to one little old lady sitting in a small, dark apartment in Memphis. Laura Bullion died in obscurity eight years before the movie

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, starring Paul Newman and Robert Redford, revitalized the almost-forgotten semilegend in which she had played a minor but authentic part.

Why It’s In My Stack: Like many of you, my depth of knowledge about Butch Cassidy is only as thick as a daguerrotype photo print and about as long as a two-hour movie. Leerhsen’s biography of the outlaw looks like a vibrant and entertaining way to go deeper.

The Best Poems of Jane Kenyon

by Jane Kenyon

(Graywolf Press)

Jacket Copy: Published twenty-five years after her untimely death,

The Best Poems of Jane Kenyon presents the essential work of one of America’s most cherished poets―celebrated for her tenacity, spirit, and grace. In their inquisitive explorations and direct language, Jane Kenyon’s poems disclose a quiet certainty in the natural world and a lifelong dialogue with her faith and her questioning of it. As a crucial aspect of these beloved poems of companionship, she confronts her struggle with severe depression on its own stark terms. Selected by Kenyon’s husband, Donald Hall, just before his death in 2018,

The Best Poems of Jane Kenyon collects work from across a life and career that will be, as she writes in one poem, “simply lasting.”

Opening Lines: (“From Room to Room”)

Here in this house, among photographs

of your ancestors, their hymnbooks and old

shoes...

I move from room to room,

a little dazed, like the fly. I watch it

bump against each window.

I am clumsy here, thrusting

slabs of maple into the stove.

Blurbworthiness: “The poems of Jane Kenyon are lodestars. I can think of no better way to navigate life than to keep her work close, as I have always done. It’s thrilling to now have this great parting gift from Donald Hall―his loving, intimate, discerning selection of the best of her poems.” (Dani Shapiro, author of

Inheritance)

Why It’s In My Stack: Otherwise, Kenyon’s collection of “new and selected poems,” which was published shortly after her death in 1995, remains one of my absolute favorite collections by a poet, contemporary or otherwise. Like Dani Shapiro, I keep Kenyon and her lodestar words close to me and within easy reach. I don’t know how many of the “greatest hits” collected here will be new to me, but a return trip to her work is overdue.

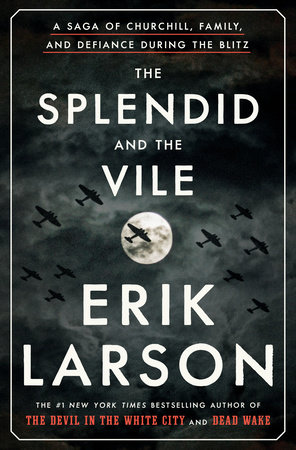

The Splendid and the Vile

by Erik Larson

(Crown)

Jacket Copy: On Winston Churchill’s first day as prime minister, Adolf Hitler invaded Holland and Belgium. Poland and Czechoslovakia had already fallen, and the Dunkirk evacuation was just two weeks away. For the next twelve months, Hitler would wage a relentless bombing campaign, killing 45,000 Britons. It was up to Churchill to hold his country together and persuade President Franklin Roosevelt that Britain was a worthy ally—and willing to fight to the end. In

The Splendid and the Vile, Erik Larson (author of

The Devil in the White City) shows, in cinematic detail, how Churchill taught the British people “the art of being fearless.” It is a story of political brinkmanship, but it’s also an intimate domestic drama, set against the backdrop of Churchill’s prime-ministerial country home, Chequers; his wartime retreat, Ditchley, where he and his entourage go when the moon is brightest and the bombing threat is highest; and of course 10 Downing Street in London. Drawing on diaries, original archival documents, and once-secret intelligence reports—some released only recently—Larson provides a new lens on London’s darkest year through the day-to-day experience of Churchill and his family: his wife, Clementine; their youngest daughter, Mary, who chafes against her parents’ wartime protectiveness; their son, Randolph, and his beautiful, unhappy wife, Pamela; Pamela’s illicit lover, a dashing American emissary; and the advisers in Churchill’s “Secret Circle,” to whom he turns in the hardest moments.

The Splendid and the Vile takes readers out of today’s political dysfunction and back to a time of true leadership, when, in the face of unrelenting horror, Churchill’s eloquence, courage, and perseverance bound a country, and a family, together.

Opening Lines: No one had any doubt that the bombers would come. Defense planning began well before the war, though the planner had no specific threat in mind. Europe was Europe. If past experience was any sort of guide, a war could break out anywhere, anytime.

Why It’s In My Stack: Though I’ve yet to read any of Larson’s books (they’re all in my TBR pile!), his treatment of the Blitz looks like a good place to start. Bombs away and here we go!

Dressed All Wrong For This

by Francine Witte

(Blue Light Press)

Jacket Copy: Robert Olen Butler, author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning

A Good Scent from a Strange Mountain, had this to say about the new collection of flash fiction by Francine Witte: “

Dressed All Wrong For This is a splendid demonstration of the depth and range of the short-short story, an art form whose relevance and influence are rapidly growing in this digital age of compressed communication. Francine Witte brilliantly illuminates nuanced truths of the human condition in this collection, truths that could be expressed in no other way.”

Opening Lines: She became like a fish out of it. Dizzy. Always dizzy. And dry.

She would ready her arms for floating. Let them stretch out long and perpendicular. But nothing. Always nothing.

She thought of how she got here. Days and days of scorching sunlight. And other obvious signs. In fancy restaurants, when conversation turned to global warming, for instance, she said she would rather talk about film.

(From the opening story “When There Was No More Water”)

Blurbworthiness: “With

Dressed All Wrong For This, Francine Witte has created an illuminated manuscript of life at a slant: where we encounter a woman who loses her “husband weight,” Suzo the clown and his many wives, a shadow that takes matters into its own hands. Rarely does one come across a story collection so astonishingly original, language so fresh, and surreal writing so rife with what is real to us all.” (Robert Scotellaro, author of

Bad Motel)

Why It’s In My Stack: I’ll make this quick: Francine Witte writes with tectonic plates, pressing and squeezing words until they are compressed into gems. Her flash fiction short-short stories sparkle. I plan to pair

Dressed All Wrong For This with Witte’s new poetry collection,

The Theory of Flesh.

The Center of Everything

by Jamie Harrison

(Counterpoint)

Jacket Copy: For Polly, the small town of Livingston, Montana, is a magical ecosystem of extended family and raw, natural beauty governed by kinship networks that extend back generations. But the summer of 2002 finds Polly at a crossroads. A recent head injury has scattered her perception of the present, bringing to the surface events from thirty years ago and half a country away. A beloved friend goes missing on the Yellowstone River as Polly's relatives arrive for a reunion during the Fourth of July holiday, dredging up difficult memories for a family well acquainted with tragedy. Search parties comb the river as carefully as Polly combs her memories, and over the course of one fateful week, Polly arrives at a deeper understanding of herself and her larger-than-life family. Weaving together the past and the present, bounded by the brisk shores of Long Island Sound and the landscape of big-sky Montana,

The Center of Everything examines with profound insight the nature of the human condition: the tribes we call family, the memories and touchstones that make up a life, and the loves and losses we must endure along the way.

Opening Lines: When Polly was a child, and thought like a child, the world was a fluid place. People came and went and never looked the same from month to month or year to year. They shifted bodies and voices—a family friend shaved a beard, a great aunt shriveled into illness, a doctor grew taller—and it would take time to find them, to recognize them.

Polly studied faces, she wondered, she undid the disguise. But sometimes people she loved disappeared entirely, curling off like smoke.

Why It’s In My Stack: I’ve been looking forward to holding Jamie Harrison’s next novel in my hands ever since the release of

The Widow Nash two years ago. Based on Harrison’s other work,

The Center of Everything is bound to delight and satisfy. Side note: I made my home in Livingston for a brief, windy spell in the mid-1980s, so I automatically gravitate toward any book set there.

The Impossible First

by Colin O’Brady

(Scribner)

Jacket Copy: Prior to December 2018, no individual had ever crossed the landmass of Antarctica alone, without support and completely human powered. Yet, Colin O’Brady was determined to do just that, even if, ten years earlier, there was doubt that he’d ever walk again normally. From the depths of a tragic accident, he fought his way back. In a quest to unlock his potential and discover what was possible, he went on to set three mountaineering world records before turning to this historic Antarctic challenge. O’Brady’s pursuit of a goal that had eluded many others was made even more intense by a head-to-head battle that emerged with British polar explorer Captain Louis Rudd—also striving to be “the first.” Enduring Antarctica’s sub-zero temperatures and pulling a sled that initially weighed 375 pounds—in complete isolation and through a succession of whiteouts, storms, and a series of near disasters—O’Brady persevered. Alone with his thoughts for nearly two months in the vastness of the frozen continent—gripped by fear and doubt—he reflected on his past, seeking courage and inspiration in the relationships and experiences that had shaped his life. Honest, deeply moving, filled with moments of vulnerability—and set against the backdrop of some of the most extreme environments on earth, from Mt. Everest to Antarctica—

The Impossible First reveals how anyone can reject limits, overcome immense obstacles, and discover what matters most.

Opening Lines: I started thinking about my hands.

That was my first mistake.

After forty-eight days and more than 760 miles alone across Antarctica, the daily ache of my hands—cracked with cold, gripping my ski poles twelve hours a day—had become like a drumbeat, forming the rhythm of my existence.

Blurbworthiness: “Suspenseful, soul-searching, and at times metaphysical as O’Brady endures an endless sheet of white and ice...The book is a testament to the human soul and the amazing feats we can accomplish with training, willpower, and the singular resilience of the mind. You will learn from and be inspired by it.” (Buzz Bissinger, author of

Friday Night Lights)

Why It’s In My Stack: Earlier this year, I traveled across the vast icy desert of Antarctica. I wasn’t alone: I was accompanied by Apsley Cherry-Garrard and his classic adventure book

The Worst Journey in the World—a narrative of walking and sledding across the continent in the early 1910s with details so intense I braved frostbite to turn the pages. So, Antarctica has been on my mind a lot. O’Brady’s solo account is now perched near the icy peaks of my towering to-be-read mountain. I can’t wait to freeze again.

Afterlife

by Julia Alvarez

(Algonquin Books)

Jacket Copy: Antonia Vega, the immigrant writer at the center of

Afterlife, has had the rug pulled out from under her. She has just retired from the college where she taught English when her beloved husband, Sam, suddenly dies. And then more jolts: her bighearted but unstable sister disappears, and Antonia returns home one evening to find a pregnant, undocumented teenager on her doorstep. Antonia has always sought direction in the literature she loves—lines from her favorite authors play in her head like a soundtrack—but now she finds that the world demands more of her than words. Afterlife, the first adult novel in almost fifteen years by the bestselling author of

In the Time of the Butterflies and

How the García Girls Lost Their Accents, is a compact, nimble, and sharply droll novel. Set in this political moment of tribalism and distrust, it asks: What do we owe those in crisis in our families, including—maybe especially—members of our human family? How do we live in a broken world without losing faith in one another or ourselves? And how do we stay true to those glorious souls we have lost?

Opening Lines: She is to meet him / a place they often choose for special occasions / to celebrate her retirement from the college / a favorite restaurant / and the new life awaiting her / a half-hour drive from their home / a mountain town / twenty if she speeds in the thirty-mile zone / Tonight it makes more sense / a midway point / to arrive separately / as she will be driving down from her doctor’s appointment / she gets there first / as he will be driving from home / he should have been there before her / she starts calling his cell / after waiting ten, twenty minutes / he doesn’t answer

Blurbworthiness: “Ravishing and heartfelt,

Afterlife explores the complexities of familial devotion and tragedy against a backdrop of a world in crisis, and the ways in which we struggle to maintain hope, faith, compassion and love. This is Julia Alvarez at her best and most personal.” (Jonathan Santlofer, author of

The Widower’s Notebook)

Why It’s In My Stack: I was blown away by the Prologue, whose opening lines I quoted above. It continues on in that fashion / fragments sliced by backslashes / for three pages / titled “Broken English” / the parts adding up to the whole. It reflects, in concrete form, the stuttering thoughts which swirl and dive-bomb our minds in times of grief. And it made me sit up and take notice that here was something fresh, something visceral, something that might make me cough up tears as the pages go on. (The rest of

Afterlife is told in the “normal” way, sans backslash interruption.)