Showing posts with label Joyce Carol Oates. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Joyce Carol Oates. Show all posts

Friday, August 16, 2019

Friday Freebie: Tell Me Who We Were by Kate McQuade

Congratulations to Rhonda Lomazow, winner of the previous Friday Freebie contest: Someone We Know by Shari Lapena.

This week’s giveaway is for Tell Me Who We Were by Kate McQuade. Two lucky readers will each win a hardcover copy of the book (dressed in that gorgeous, haunting cover). Here's what Joyce Carol Oates had to say about it: “These are stories of magical lyricism, contemporary in their exploration of the obsessions of girls and young women, mythic in their scope and mystery. Remarkable.” Keep scrolling for more about the novel and how to enter the contest...

Lyrical, intimate, and incisive, Tell Me Who We Were explores the inner worlds of girls and women, the relationships we cherish and betray, and the transformations we undergo in the simple act of living. It begins with a drowning. One day Mr. Arcilla, the romance language teacher at Briarfield, an all-girls boarding school, is found dead at the bottom of Reed Pond. Young and handsome, the object of much fantasy and fascination, he was adored by his students. For Lilith and Romy, Evie and Claire, Nellie and Grace, he was their first love, and their first true loss. In this extraordinary collection, Kate McQuade explores the ripple effect of one transformative moment on six lives, witnessed at a different point in each girl’s future. Throughout these stories, these bright, imaginative, and ambitious girls mature into women, lose touch and call in favors, achieve success and endure betrayal, marry and divorce, have children and struggle with infertility, abandon husbands and remain loyal to the end.

If you’d like a chance at winning Tell Me Who We Were, simply e-mail your name and mailing address to

Put FRIDAY FREEBIE in the e-mail subject line. Please include your mailing address in the body of the e-mail. One entry per person, please. Despite its name, the Friday Freebie remains open to entries until midnight on Aug. 22, at which time I’ll draw the winning names. I’ll announce the lucky readers on Aug. 23. If you’d like to join the mailing list for the once-a-week newsletter, simply add the words “Sign me up for the newsletter” in the body of your email. Your e-mail address and other personal information will never be sold or given to a third party (except in those instances where the publisher requires a mailing address for sending Friday Freebie winners copies of the book).

Want to double your odds of winning? Get an extra entry in the contest by posting a link to this webpage on your blog, your Facebook wall or by tweeting it on Twitter. Once you’ve done any of those things, send me an additional e-mail saying “I’ve shared” and I’ll put your name in the hat twice.

Monday, October 15, 2018

My First Time: Lee Zacharias

My First Lesson Learned

If book tours were a thing when Houghton Mifflin published my first novel in 1981, I’m sure I would have had one. My publisher had big expectations: ads in the Washington Post and New York Times, an auction for paperback rights with a minimum bid of six figures, a first press run of 30,000 copies. That the novel didn't sell anywhere near 30,000 copies, that the one company offering the minimum six figures was immediately sold to another that was iffy about my novel—let’s just say those things happened later. The excitement of my editor, the offshoot sales—Book of the Month Club, Redbook, foreign rights—actually seemed normal. Never mind that my first book, a collection of short stories, had been published with a press run of 1,000 by a university press. I was teaching at Princeton and often had lunch with Joyce Carol Oates. At parties I met Nobel laureates at the kitchen sink and overheard authors like Peter Benchley (remember Jaws?) saying that they didn’t feel they’d been published if the first press run wasn’t 100,000. At readings I sat next to Carlos Fuentes. Richard Ford was a good friend. Yet once, as Joyce and I were walking back from lunch through the Princeton Gardens, she stopped to exclaim, “This is Princeton, Lee!” I recognized the awe in her voice, because I too was from a lower middle class family who could never have dreamed of sending a child to Princeton, let alone having one who taught there.

So many copies of my first novel were remaindered that a company that makes safes out of leftover books bought up mine. Lessons was at the top of the stack in one of their ads in Parade, cover open to reveal the hollowed out pages and velvet lining, pearls spilling from inside. “You can’t judge a book by its cover” was the ad’s slogan, and though the small print warned that you couldn’t specify a title, the clerk I spoke with on the phone was so impressed that I was the author she gave me the company president’s number. The president promised to send as many copies as I wanted as soon as she received my check. I had given up on receiving them by the time her apology arrived, my uncashed check enclosed. When she had gone to the warehouse, my title was out of stock, she explained, ending with a cheery “It truly was a best seller.”

Fast-forward to 2014. I’ve just published a collection of personal essays, which I’ve been writing with some success over the past decade. My publisher is an excellent small press, and by now even a book of essays requires a tour. Asheville’s Malaprops is a prize—nearly all of my friends have read there, but the store turned me down the year before, when a much smaller press issued my second novel. I explore the newly hip downtown and take a picture of The Only Sounds We Make, prominently displayed in the window next to all the best-selling authors with new books. Unexpected friends show up—friends from Chattanooga who happened to be in town. Another friend, strangers. It’s not a huge audience, but as I read I can see on their faces I have their full attention. There’s not a moment of awkward silence when I ask for questions, and we’re in the middle of a lively conversation when a siren goes off. Everyone looks at one another. No one seems quite sure what to do, but then the fire trucks arrive, and in come the firemen in full gear, bearing axes. The store is evacuated. For a while my audience stands on the street with me, though as time drags on all but my friends drift away. It’s a false alarm—sort of. Malaprops sits on a hill, and beneath the back of the store, facing a side street, there is a popular restaurant with a kitchen that occasionally has a pan overheat. But by the time the firemen depart, hoses unused, the bookstore has closed. Still, if you can leave Princeton and not publish another novel for years, you can leave Malaprops without a single sale knowing that at least a lot of people own book safes with your name on them, and maybe, just maybe, the people who heard you tonight will remember it when you come back to read from your next book.

Lee Zacharias is the author of a collection of short stories, Helping Muriel Make It Through the Night; three novels, Across the Great Lake, Lessons, and At Random; and a collection of personal essays, The Only Sounds We Make. At Random was a finalist in literary fiction for the 2013 International Book Awards, the National Indie Lit Awards, and the USA Best Book Awards. Her fiction and nonfiction have appeared in numerous journals, including, among others, The Southern Review, Shenandoah, Five Points, Gettysburg Review, and Crab Orchard Review.

My First Time is a regular feature in which writers talk about virgin experiences in their writing and publishing careers, ranging from their first rejection to the moment of holding their first published book in their hands. For information on how to contribute, contact David Abrams.

Thursday, October 5, 2017

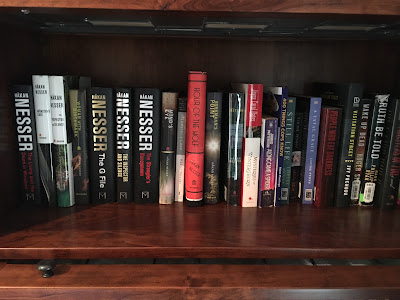

The Eclectic Shelf: Eric Rickstad’s Library

Reader: Eric Rickstad

Location: Vermont

Collection size: No idea, a lot. Books everywhere.

The one book I’d back into a burning building to rescue: My 1992 Best American Short Stories

Favorite book from childhood: Danny, Champion of the World by Roald Dahl

My guilty pleasure: Best American Short Stories Collection

OK, I don’t really have a library. Not in the sense that I think of a library, that vast room with shelves from floor to ceiling, a place worthy of Colonel Mustard and his pipe wrench. But I do have a lot of bookshelves and cabinets.

This is what’s left of what was my Best American Short Stories and O’Henry Awards collection from 1974-2005. I lost so many editions to severe water damage, it kills me. I first read BASS in the early ’90s when in college. These stories opened up my mind to what was possible with words, precise language, and love of craft. Each was a gem that excited me to read more ravenously than ever, and a challenge to write my best. Joyce Carol Oates. Alice Munro. John Edgar Wideman. Harlan Ellison. Alice Adams. Rick Bass. Denis Johnson. And on and on and on. Who were these word conjurers of tales so strange and wondrous and singular? I devoured the stories, and I bought each subsequent edition in the years to come, along with the O’Henry collections. After reading the first copy I ever bought in 1992, I searched for past editions and bought them whenever I was in a used bookshop. Searching for and finding them was a feverish, earnest pursuit. Of course, they led me to the literary magazine world, and I gobbled up every copy of Cimarron Review, Tri-Quarterly, Boulevard, Prairie Schooner, Ploughshares, and dozens of others in the periodicals section of the University of Vermont’s Bailey Howe Library. There was no going back. The door was flung wide open.

When several boxes of my editions got ruined by water damage during a move, I felt gut punched. I could recall each story in my mind and where I was when I read it the first of many, many times, what it made me feel and think, and how it made me want to write. I remember I started Kate Braverman’s “Tall Tales from the Mekong Delta” on the front porch of my college apartment and had to finish it inside when a downpour struck out of the blue. I read Denis Johnson’s “Emergency” while waiting for my clothes to wash at the Laundromat. And I re-read it and re-read it and re-read it. What. Was. This? Magic.

When I lost all those editions in the mid 2000s, I could have easily searched for and bought online all the used editions I wanted, with a few clicks. I could have owned them all again, and more. I still could. But, no. It wouldn’t be the same, it wouldn’t be them: found in the back labyrinth of stacks in ancient used bookstores, dog-eared and tattered and stained, sentences and words and entire pages underlined during those moments of revelation upon my first read of them. So, I salvaged those books I could from the water damage. Luckily, among the books that were salvageable included the first one I bought in 1992. They occupy the top shelf where they belong, and once in a while I’ll take them down and be transported, not just back into the world of the stories, but to the time I first read that story. I don’t keep them in any order—as you can see, one is upside down. I read them, and I still take notes in them. They are there to be read.

I try to arrange books by author’s last name, alphabetically. It’s hopeless. As I buy more books, it would mean having to get rid of older books to accommodate new books, and I buy new books by the dozens. I gave up on shelves for a spell, and the new books just pile up. This shelf demonstrates an attempt at order, and the eclectic array on any given shelf. New books. Used books. Hardcovers and paperbacks. Fiction and nonfiction. Genre novels by John Sandford, Don Winslow and Nic Pizzolatto live among Carson Stroud, Carlos Ruiz Zafon, and Mia Siegert. Strewn among them are the nonfiction work On Fire by the late Larry Brown, Animals Make Us Human by Temple Grandin, Writing 21st Century Fiction by Donald Maass, and Under the Stars by Dan White, a history of camping in the U.S. Near one of Stephen King’s newer annual tomes and Donna Tartt’s latest addition in a decade, sit The Stories of Breece Pancake, a Wild Game Cookbook from the ’80s, and a favorite book of essays and photographs, with a foreword by the late Howard Frank Mosher, Deer Camp: Last Light in the Northeast Kingdom. Each shelf is its own mini collection of writers.

Sometimes, even in alphabetical order, a shelf will represent just a few authors in a specific genre, like this one, which is Hakan Nesser-centric, and mostly mystery/crime genre.

Other times, certain kings of the book world get their own shelf, or shelves.

There are shelves with just cookbooks, and just children’s books, rock n’ roll biographies, essays, philosophy, Judaism, hunting and fishing, and art. I keep building or buying shelves and giving away books I love to others, so they can enjoy them. I stack them at the bedside table, and the floor, and on the stairs, and I box them up and put boxes in the closet. I think I may well need a library.

Eric Rickstad is the New York Times, USA Today, and international bestselling author of The Canaan Crime Series: Lie in Wait, The Silent Girls, and his newest novel, The Names of Dead Girls. Dark, disturbing and compulsively readable psychological thrillers set in northern Vermont, the series is heralded as intelligent, profound, heartbreaking and mind shattering. His first novel Reap was a New York Times noteworthy novel. His fifth novel, What Remains of Her, is poised to be the most addictive and creepy read of the summer of 2018. Rickstad lives in his home state of Vermont.

My Library is an intimate look at personal book collections. Readers are encouraged to send high-resolution photos of their home libraries or bookshelves, along with a description of particular shelving challenges, quirks in sorting (alphabetically? by color?), number of books in the collection, and particular titles which are in the To-Be-Read pile. Email thequiveringpen@gmail.com for more information.

Monday, August 1, 2016

Our First Time: Jennifer Spiegel, Lynn Marie Houston, and Susan Allspaw Pomeroy

My First Time is a regular feature in which writers talk about virgin experiences in their writing and publishing careers, ranging from their first rejection to the moment of holding their first published book in their hands. Today’s guests are Jennifer Spiegel, Lynn Marie Houston, and Susan Allspaw Pomeroy, the editors of Dead Inside: Poems and Essays About Zombies. The literary collection brings together twenty-six poems and six essays inspired by the zombies and characters of AMC’s hit television show The Walking Dead. More about the editors can be found at the end of the blog post.

My First Monster

We’re a pretty diverse team of academics, real-world professionals, and writers. The big commonality—not the only one, but the major one—is our crazy love for AMC’s The Walking Dead. So we made an anthology, edited it, and each contributed to it. Dead Inside: Poems and Essays About Zombies is our baby together. Lynn’s very own press, Foiled Crown Books, published it; Susan’s poems inspired it; Jennifer is the most obsessed. But gathering around the topic of “firsts” is, in itself, tough. So we decided to discuss our first monster.

Jennifer: Well, in all honesty, my first “monster” was probably Jaws—which scarred me for life. I also had a recurring dream with a gold, metallic sea monster who looked strangely like C-3P0 (but predated him). The sea monster used to “seduce” my mom into a big pool. I’m not sure this counts, though. I have body-of-water issues. The water as monster.

In truth, I’ve spent minimal time in the horror genre. I’ve only read the first graphic novel of The Walking Dead. I’ve read Frankenstein. One Stephen King novel (The Stand). Some Benjamin Percy. I never got into the Vampire thing. I miss all the horror flicks. I can’t remember the last one I saw.

But zombies. . . I like the zombie-thing. The zombie is really my first monster. What are each of YOUR personal monsters?

Lynn: I actually started with the horror flicks at a young age, maybe too young. While my mother was getting the weekly groceries, my father used to let me and my younger brother watch the scary movie that came on every Saturday afternoon from 2:00 to 4:00 p.m. But as soon as we heard the car in the driveway, he would change the channel. There were so many “B” movies from the seventies and eighties whose final moments I never saw. But later, at night, I would imagine their endings. And that’s probably how I developed the mindset of a writer—lying there in the dark imagining the endings to scary movies I wasn’t allowed to finish watching.

Jennifer: Are we talking The World Beyond (wasn’t that a thing?) or the slew of demon-possession films that haunted Gen X youth?

Lynn: Mostly haunted-house-type stuff, with some Satanic-children stuff thrown in—

Jennifer: Oh yeah, I forgot about all those Satanic children!—

Lynn: Which is exactly what my devout Catholic mother didn’t want us watching. (P.S. I have the best dad!). But my mother wasn’t totally wrong. My early childhood fascination with monsters led me to some dark places. It prompted me to have a recurring nightmare about a female werewolf who made me bring her men so she could eat them. I’ve had this same dream numerous times even into adulthood, and I always wake up right as she comes crashing through a glass elevator to claim her prey. It’s too bad Freud didn’t do more with monsters. I’m sure he would have had a lot to say about werewolf pimps. Zombies seem tame, almost comical, compared to the fang and claw nightmares of my childhood. That is, until zombies started moving fast, à la 28 Days Later. How about that for a “first monster”? The fast zombie was an incredible way to make the whole genre scarier. Although so many of these recent innovations on ancient monsters (think sparkly vampires!) are indebted to supernatural and paranormal fiction. I haven’t read much Stephen King, but even he has written a zombie story!

Susan: I read my first Stephen King novel, The Stand, when I was fourteen. I’d already been introduced to the movie monsters of the eighties, but this post-apocalyptic tome stuck with me. So, in truth, my first monster was Randall Flagg, evil with a man’s face. Not only did I read everything King had written up until then, but I sought out any apocalypse-like stories. My first zombie movie was Night of the Comet, which was about as eighties-themed as you could get. I was obsessed...partly because the worlds of these novels and movies tapped into our basest survival instincts, and at that time in my life, I needed stories in which people survived the unthinkable. I (poorly) wrote horror stories throughout high school, and even though I left fiction behind in college, the obsession stuck.

Zombies are the easiest way into my apocalyptic-survival obsession, which is really about all the rest of the humans.

Jennifer: I share this obsession with the apocalypse. And, really, it’s about the humans. Less monster-centric, more human-oriented. I think it’s interesting to note that there are different kinds of monsters out there in pop culture- and literary-land. When we were little, there seemed to be this preponderance of demon-possessions, haunted houses, The Exorcist, The Omen, et al. The monster came from within, maybe? There was also this lack of control. Escape seemed to have less to do with strategy, and more to do with luck. The move to the apocalypse and zombie stuff has to do with externalities. The essential human being is put in dire circumstances and forced to deal.

So we’re writers. As a writer, what is the monster appeal?

Lynn: I think I’ve always been curious about what part of me was monstrous enough as a child to invent the fantasy of a werewolf pimp. Beneath the surface somewhere, I was both parts of that narrative—femme fatale and innocent, villain and heroine. And it reflected something complex about my interpersonal relationships, even at an early age, how I felt, even then, like I was constantly mediating between bullies and their victims.

I think the idea of a monster is like a blank canvas for representations of moral questions—what makes us human and are those qualities good? The monster-figure tries to account for what is not wholly good in us, the parts of ourselves we want to hide away in the dark. The cultural space of the monster allows that discussion to come into the light.

Susan: Exactly, Lynn!

Jennifer: So, in philosophical terms, monsters are an opportunity for exploring the problem of evil. I like the word Lynn used: canvas.

Susan: Monsters give us a creative way to look in a mirror at our humanity without (necessarily) putting a human face on our poorest qualities. Poetry and its penchant for metaphor really lent itself to this endeavor for me, and while I started writing zombie poems as a distraction from what I thought was “more serious” work, they became the best way to tell the story that I was struggling with. A book that completely turned the tables for me, though, was Zombie by Joyce Carol Oates. This was an incredibly fast and dark book that really isn’t about zombies….It’s the mind of a man who wants to escape his own mind. Incredibly creepy, it haunted me, but gave me leave to strive to a more artistic approach to our base darkness.

Also, writing zombies is fun.

Jennifer: I have to admit that I have never tried my hand at zombie fiction. A friend of mine told me about Sarah Lyons Fleming, who—I don’t want to get this wrong—wrote some self-published zombie books, and I read the first one. Emily St. John Mandel’s Station Eleven did actually whet my appetite for writing something apocalyptic. But it hasn’t happened. Definitely, though, the appeal is in how humans deal.

Susan: So if our monsters are mirrors, what do you think about the obsession for writers at large that helped create Dead Inside?

Jennifer: I think it really makes a lot of sense. Dead Inside, zombie-inspired, a tribute of sorts to The Walking Dead on TV, comes together in the midst of a perfect storm. The stakes are high; the plot is well-drawn. The monsters are externalities in form, and brainless—which means that it’s all about the humans, being human. A friend of mine liked the show less because the zombies were brainless. She said they were too easy to outsmart. I’d suggest this contrasts sharply with what is human. It sets us up to focus on the quandary of being human. The show is character-rich. Time is strained. Setting is booby-trapped. Tone is somber (this, I personally think, is one of the biggest strengths of the show; it refuses to degenerate into cheesiness, always going for realism. The painstaking humanity under pressure is the appeal).

Lynn: I like the classic nature of the zombies—slow-moving, brainless—in The Walking Dead. The writers of this show haven’t tried to re-invent the monster. Zombies are dangerous for the same reason democracy is dangerous—sheer masses, brute force. When enough of them pile on one side of a fence or door, they get through it. No brains needed. And that, for me as an intellectual, is the scariest thing ever. Our country run by brainless idiots, laws decided by people who couldn’t pass a basic freshman composition course because of the logical fallacies they commit. It scared John Adams, too, when he helped found our country. In a letter to his wife on July 3, 1776, he writes about his anxieties over the concept of majority rule: “The people will have unbounded power, and the people are extremely addicted to corruption and venality.” This next election feels like the apocalypse, amiright?

Jennifer: Someone just asked me if I think the zombies are symbolic. I think they may be, but I wouldn’t push this too far, probably. I think it’s really focused on the people, and the potential for symbol is mostly in the people. Rick as symbol, Morgan as symbol, Daryl as symbol, Carol as symbol, and Negan as symbol. The brainlessness draws our attention to those with brains. That said, I think there’s symbolic value—quite a bit of it—in the zombie horde. The horde of brainlessness...

Susan: The collective unconsciousness of humanity is the thing that I think draws us all to this topic... that we are all faced with the same vulnerabilities and collective fear of the unknown or unfamiliar. The film I Am Legend haunted me for just this reason—what is left when we are reduced past the facades we put on every day to our most basic humanity? How is life changed for us, and how do we change the world around us, when we become the monster in the dark (Negan), or the man desperately clinging to his mask (Rick)?

Jennifer: I Am Legend got to me, too.

Susan: But I am married to a scientist. And part of the draw of zombie stories for me is our ability to imagine a feasible (albeit far-fetched) reality in which we might be able to reason our way to resolution. If the story isn’t character-rich, as Jennifer says, if the story doesn’t present us with danger that we know but ignore, as Lynn says, then the story is too far removed from me for a visceral response. And that’s the key that I think every writer strives to evoke in his or her audience—a visceral response.

Jennifer: Well, to be very writer-specific, we might ask what our own “writing monsters” are, or what challenges/obstacles do you face as a writer, especially as a “professional writer” (if we can call ourselves that)?

I could identify a ton! First and foremost is the vocational challenge. I’d like to think that I’m trying to make candor part of my aesthetic; I really try to be honest in my writing (who doesn’t?). So, in the interest of candor, let me say that choosing to go “professional” is my biggest monster. I’ve found that I’m a devoted writer; I’ll write like a fiend, meet deadlines, edit and revise, read voraciously. I’ve simultaneously found that I lack business savvy, and I offer little to the world of “real work.” Whatever that is. I’m sounding too cynical. I can hold down a job; it’s just that I’d always rather write or talk about writing. That’s my biggest monster.

Then there are the little monsters. My fiction voice tends to be more serious than my nonfiction voice. I don’t know what’s going on there. A monster?

I’ll expose myself in crazy ways for my writing; I really will. I like, very much, the idea of using my own life as an artistic palette. For the sake of narrative, I will truly violate my own privacy. The monster is, however, that I am not an island—not even close. I’m married with kids. So, I have to consider their privacy. This definitely introduces a tension in my writing—not a bad one. But I feel more drawn to fiction because I get to mess with the truth. Writing well, for me, often involves balancing on this tightrope of self-exposure and self-protection.

Lynn: I get how monstrous it is to live as a writer in terms of the ways you expose your personal life. I had a boyfriend once accuse me of purposefully creating drama in our relationship just so that I could write about it later. What does that Facebook meme say? Be careful not to make a writer mad or she will write about you? Yeah, that ex-boyfriend has become the villain in some of my creative nonfiction stories.

The thing I struggled with about that writing situation was ethical: if it was emotionally abusive of him to claim that I was “crazy” when I pointed out his wrongdoings, is it emotionally abusive of me in turn to write him as “crazy”? My essay in Dead Inside asks questions about this dynamic: how can the victims of abuse avoid creating more victims?

There’s no easy answer here, but this touches on probably my biggest writing monster, and it’s the reason I switched from academic writing (where five people will read your dissertation, if you’re lucky) to creative writing—the fear that no one will know me. The monster that haunts me, that pushes me to write, is the desire to be known. (And loved? I’d settle for known. It’s already asking enough).

Jennifer: Kudos to you for acknowledging that. My guess is that most writers want to be known.

Susan: My writing monster has always been the obsession…which includes this latest jag of zombie poems. I will create a maelstrom around a particular topic, and sometimes this obsession is the thing that gets me to write about the thing that really matters. For instance, when I was writing my first poetry collection, I started obsessing about Antarctica; lo and behold, a book of Antarctic poems was born. While trying to focus on Little Oblivion, I wrote poems (an entire book’s worth) about two fictitious men and their relationship. So I suppose I’m saved by my writing monster, even though its distraction means I take longer to get where I’m going.

Jennifer: Do monsters figure into your own work, apart from this project?

I think my fiction “worries” over the problem of evil, the monster within, the monster with a human face, how seemingly normal people are secret monsters, how everyone might really be a monster, how the monster is not so far-fetched. How’s that for stream of consciousness?

Lynn: Like Jennifer was saying earlier in her reading of The Walking Dead, in my work people are the monsters. I write a lot about relationships between men and women in both my poetry and my creative nonfiction. Romantic relationships are filled with monstrosity because Hollywood narratives have led us to believe that true human connection is something other than what it really is. Although I don’t often deal with the fairytale genre, I essentially write about how Snow White and her prince become The Munster family.

Susan: Someone once told me that my poems seemed to be a distiller of identity; that they hold a mirror up to the self and allow us to see ourselves as strangers, all the better to experience and react to our raw emotions. So while these are my first external monsters, the monsters in my other work come out of the self.

Lynn: I wanted to conclude by saying that the zombie horde is a powerful force because of its numbers, just as the survivors of an apocalypse can do better things for each other when they band together. We saw this in the Alexandria community in The Walking Dead, and also in the Hilltop community. When the survivors collaborate, they can get haircuts again, hot showers, grow crops. We won’t mention how that is also how things start to fall apart, when you want to stand up for and protect a larger group, your tribe, or how individual morality can corrode a group. This project, Dead Inside—the three of us producing this volume of twenty-six poems and six essays on zombies—is a testament to the power of the group. It has been a fantastic experience to work together with the two of you.

Jennifer: Likewise, I’m sure.

Susan: Indeed! The human, thinking collective wins over the horde every time.

Lynn Marie Houston holds a Ph.D. in English from Arizona State and is currently completing her M.F.A. at Southern Connecticut State University. She is the author of The Clever Dream of Man (Aldrich Press), a book of poetry about her relationships with men which won 1st place in the 2016 Connecticut Press’s statewide literary competition and then went on to take 2nd place in the nationwide contest of the National Federation of Press Women. Her creative nonfiction has appeared in Word Riot, Squalorly, Bluestem, Full Grown People, Cleaver, and other journals. She has held writing residencies at the Vermont Studio Center and the Sundress Academy for the Arts. For more about her work, visit lynnmhouston.wordpress.com

Susan Allspaw Pomeroy defies writerly expectations by marrying the life of a poetess with that of a scientist/techie. Not surprisingly, the poet takes precedence. She is the author of Little Oblivion, a poetry collection that gives voice to Antarctica’s stark, impressionable landscape—which came out of her voyage to the South Pole during her 15-year tenure with the US Antarctic Program. Though equipped with the requisite English and Creative Writing degrees, she’s also a security program manager for an email service provider. Additionally, she’s been a visiting writer for universities in Denver.

Jennifer Spiegel is the author of two books, The Freak Chronicles (a story collection) and Love Slave (a novel). Currently, she is at work on both a novel and a memoir-in-almost-real-time. She is also half of Snotty Literati, a book-reviewing gig with Lara Smith (onelitchick.com). Besides writing, Jennifer teaches and does the mom-thing. When she watches TV with her husband, she pretends it’s an academic endeavor.

Labels:

Benjamin Percy,

Joyce Carol Oates,

My First Time,

Stephen King

Thursday, July 14, 2016

Front Porch Books: July 2016 edition

Front Porch Books is a monthly tally of books—mainly advance review copies (aka “uncorrected proofs” and “galleys”)—I’ve received from publishers, but also sprinkled with packages from Book Mooch, independent bookstores, Amazon and other sources. Because my dear friends, Mr. FedEx and Mrs. UPS, leave them with a doorbell-and-dash method of delivery, I call them my Front Porch Books. In this digital age, ARCs are also beamed to the doorstep of my Kindle via NetGalley and Edelweiss. Note: many of these books won’t be released for another 2-6 months; I’m here to pique your interest and stock your wish lists. Cover art and opening lines may change before the book is finally released. I should also mention that, in nearly every case, I haven’t had a chance to read these books.

Angels of Detroit

by Christopher Hebert

(Bloomsbury)

It may not be a rule that a novel about Detroit should contain an automobile in the first sentence, but in the case of Christopher Hebert’s new novel, the first two words “The car” seem wholly appropriate and foretell good things to come. Angels of Detroit is a big book, as in “epic big,” and I’m looking forward to settling into the passenger’s seat in the months to come.

Jacket Copy: Once an example of American industrial might, Detroit has gone bankrupt, its streets dark, its storefronts vacant. Miles of city blocks lie empty, saplings growing through the cracked foundations of abandoned buildings. In razor-sharp, beguiling prose, Angels of Detroit draws us into the lives of multiple characters struggling to define their futures in this desolate landscape: a scrappy group of activists trying to save the city with placards and protests; a curious child who knows the blighted city as her own personal playground; an elderly great-grandmother eking out a community garden in an oil-soaked patch of dirt; a carpenter with an explosive idea of how to give the city a new start; a confused idealist who has stumbled into debt to a human trafficker; a weary corporate executive who believes she is doing right by the city she remembers at its prime—each of their desires is distinct, and their visions for a better city are on a collision course. In this propulsive, masterfully plotted epic, an urban wasteland whose history is plagued with riots and unrest is reimagined as an ambiguous new frontier—a site of tenacity and possible hope. Driven by struggle and suspense, and shot through with a startling empathy, Christopher Hebert's magnificent second novel unspools an American story for our time.

Opening Lines: The car was a late-model Oldsmobile, the interior dank and musty, and the driver bore the distinctly sweet, rotting smell of overripe bananas. Lucius was his name. Thick dark hair sprouted from his knuckles in wild tufts. They were in southeastern Kansas, heading east as Patsy Cline quavered through a pair of broken speakers.

Blurbworthiness: “A Dickensian collection of Motor City characters bent on personal survival and rebuilding what they can...Ambitious, well-paced, observant—Angels of Detroit is a first-rate novel of flawed but admirable characters who want a brighter future in what one of them calls the new Old West.” (Shelf Awareness)

We Show What We Have Learned

by Clare Beams

(Lookout Books)

I’ve harvested a bumper crop of short story collections this month; so many good-looking ones keep turning up on my front doorstep...much to my delight. Chief among them is this debut by Clare Beams which comes with a front-cover endorsement by Joyce Carol Oates (“wickedly sharp-eyed, wholly unpredictable, and wholly engaging”). I am wholly ready to enter these stories (one of which, “World's End,” I already read—and loved—in One Story).

Jacket Copy: The literary, historic, and fantastic collide in these wise and exquisitely unsettling stories. From bewildering assemblies in school auditoriums to the murky waters of a Depression-era health resort, Beams’s landscapes are tinged with otherworldliness, and her characters’ desires stretch the limits of reality. Ingénues at a boarding school bind themselves to their headmaster’s vision of perfection; a nineteenth-century landscape architect embarks on his first major project, but finds the terrain of class and power intractable; a bride glimpses her husband’s past when she wears his World War II parachute as a gown; and a teacher comes undone in front of her astonished fifth graders. As they capture the strangeness of being human, the stories in We Show What We Have Learned reveal Clare Beams’s rare and capacious imagination—and yet they are grounded in emotional complexity, illuminating the ways we attempt to transform ourselves, our surroundings, and each other.

Opening Lines: “A transformational education,” the newspaper ad had promised, so we went to the Gilchrist School to find out whether that promise could include me. With its damp-streaked stone and clinging pine trees, the school looked ideal for transformations, like a nineteenth-century invalids’ home, a place where a person could go romantically, molderingly mad.

Blurbworthiness: “An elegant and assured debut, packed with confident prose—and stories with novel-like wholeness in the way of [Alice] Munro and [John] Cheever. The stories are imaginative and flecked with darkness and subtle societal commentary in the manner of Margaret Atwood; the characters are complex and rendered with psychological acuity. Smart, savage, and compulsively readable.” (Megan Mayhew Bergman, author of Almost Famous Women)

Monsters in Appalachia

by Sheryl Monks

(Vandalia Press)

Skimming through the first lines of Sheryl Monks’ stories, one thing becomes very clear: this is an author strong with voice (that impossible-to-be-taught quality good writers bring to the page, the je ne sais quoi of style). Here are just a few, randomly-chosen openers from Monsters in Appalachia:

It had come a sudden shower.

This old girl wasn’t much to look at, but she took a shine to me that wore me down after a while.

She hears the dogs coming round now, bugling louder as they draw near, bawling out in unbridled rapture.Indeed, I’m expecting plenty of “unbridled rapture” in the pages to come. These are stories I can take a shine to.

Jacket Copy: The characters within these fifteen stories are in one way or another staring into the abyss. While some are awaiting redemption, others are fully complicit in their own undoing. We come upon them in the mountains of West Virginia, in the backyards of rural North Carolina, and at tourist traps along Route 66, where they smolder with hidden desires and struggle to resist the temptations that plague them. A Melungeon woman has killed her abusive husband and drives by the home of her son’s new foster family, hoping to lure the boy back. An elderly couple witnesses the end-times and is forced to hunt monsters if they hope to survive. A young girl “tanning and manning” with her mother and aunt resists being indoctrinated by their ideas about men. A preacher’s daughter follows in the footsteps of her backsliding mother as she seduces a man who looks a lot like the devil. A master of Appalachian dialect and colloquial speech, Monks writes prose that is dark, taut, and muscular, but also beguiling and playful. Monsters in Appalachia is a powerful work of fiction.

Opening Lines: All the children had been given away, and now Darcus Mullins found herself driving the curving road up toward Isaban to look again at the burning slag heap.

Blurbworthiness: “A fresh, new voice in contemporary fiction, in stories of teenage angst, bonds of family, motherhood, and contradictions of middle age. Always surprising, these stories conjure both sorrow and mystery with intimate, loving detail.” (Robert Morgan, author of Gap Creek)

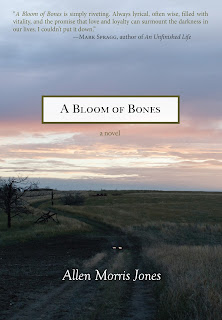

A Bloom of Bones

by Allen Morris Jones

(Ig Publishing)

In the past, I’ve sent out literary APBs for authors whose early works I loved but who then seemed to fall off the publishing radar. I was about to issue one for Allen Morris Jones because I loved his debut novel Last Year’s River and thinking about it conjures up something like the fireworks excitement with which a shy wallflower-y teenager remembers the taste of a first kiss. I should add that Allen lives less than 100 miles from me, just over a mountain pass, and I see him frequently at book events around Montana...so I know he has fallen off the radar; but it has been too long of a dry spell between novels from him (perhaps Allen feels the same way himself). And then—BOOM!—an e-galley of a new novel (his first in 15 years) landed on my Kindle, courtesy of Edelweiss. A Bloom of Bones shoots straight to the top of my TBR queue. The literary cops can ignore that APB and head on back to the donut shop.

Jacket Copy: Eli Singer, a rancher and poet in remote Eastern Montana, sees his life upended when a long-buried corpse—which turns out to be a murder victim from Eli's childhood—erodes out of a hillside on his property. This discovery forces Eli to turn inward to revisit the tragic events in his past that led to a life-changing moment of violence, while at the same time he must reach outside himself toward Chloe, a literary agent from New York whom he is falling in love with. In the tradition of such classic western writers as Thomas McGuane, James Lee Burke, Ivan Doig and Jim Harrison, A Bloom of Bones is a poignant and moving exploration of family, community, and the echoing ramifications of violence across generations, as well as a genre-subverting literary mystery.

Opening Lines: I said, “That big bullet went right on through, didn’t it?” It was too cold to snow but still it was snowing; a thin sheet of gauze twisting around the porch light.

Buddy kicked through frozen marbles of blood, scattered them, swept them aside with his boot. He knelt and rose, hoisting the body across one shoulder. Voice muffled by a wool scarf, he said, “Leaking?”

“What?”

“Is he leaking anywhere?”

“I don’t see it.”

“All right then.”

“That big bullet went plumb through, didn’t it?”

“Will you quit with the goddamned questions? Just for once?” A gentle man, Buddy rarely cussed, seldom rebuked, never raised his voice. I stood abashed, one breath from tears. He inhaled hard through his nose, shifted the body on his shoulders. “Let’s just get this done.”

Blurbworthiness: “Allen Jones’s A Bloom of Bones is simply riveting. Always lyrical, often wise, filled with vitality, and the promise that love and loyalty can surmount the darkness in our lives. I couldn’t put it down.” (Mark Spragg, author of An Unfinished Life)

Lions

by Bonnie Nadzam

(Grove Atlantic)

At the start of her new novel, Bonnie Nadzam tells us, “There were never any lions.” No, but there is some gorgeous, evocative prose in those opening lines which describe a decayed town in Colorado (see below). By the promise of those sentences alone, this will be a haunting, memorable novel to savor.

Jacket Copy: Bonnie Nadzam—author of the critically acclaimed, award-winning debut, Lamb—returns with this scorching, haunting portrait of a rural community in a “living ghost town” on the brink of collapse, and the individuals who are confronted with either chasing their dreams or—against all reason—staying where they are. Lions is set on the high plains of Colorado, a nearly deserted place, steeped in local legends and sparse in population. Built to be a glorious western city upon a hill, it was never fit for farming, mining, trading, or any of the illusory sources of wealth its pioneers imagined. The Walkers have been settled on its barren terrain for generations—a simple family in a town otherwise still taken in by stories of bigger, better, brighter. When a traveling stranger appears one day, his unsettling presence sets off a chain reaction that will change the fates of everyone he encounters. It begins with the patriarch John Walker as he succumbs to a heart attack. His devastated son Gordon is forced to choose between leaving for college with his girlfriend, Leigh, and staying with his family to look after their flailing welding shop and, it is believed, to continue carrying out a mysterious task bequeathed to all Walker men. While Leigh is desperate to make a better life in the world beyond the desolation of Lions, Gordon is strangely hesitant to leave it behind. As more families abandon the town, he is faced with what seem to be their reasonable choices and the burden of betraying his own heart. A story of awakening, Lions is an exquisite novel that explores ambition and an American obsession with self-improvement, the responsibilities we have to ourselves and each other, as well as the everyday illusions that pass for a life worth living.

Opening Lines: If you’ve ever really loved anyone, you know there’s a ghost in everything. Once you see it, you see it everywhere. It looks out at you from the stillness of a rail-backed chair. From the old 1952 Massey-Harris Pony tractor out front, its once shining red metal now a rust-splotched pink, headlights broken off. No eyes.

Picture high plains in late spring. Green rows of winter wheat combed across the flat, wide-open ground. The derelict sugar beet factory, its thousands of red bricks fenced in by chain-link clotted with Russian thistle. Farther down the two-lane highway, the moon rising like an egg over the hollow grain elevator, rusted at its seams. To the north and west, the sparsely populated town. Golden rectangles of a few lit windows floating above the plain.

They called it Lions, a name meant to stand in for disappointment with the wild invention and unreasonable hope by which it had been first imagined, then sought and spuriously claimed. There were never any lions. In fact there is nothing more to the place now than a hard rind of shimmering dirt and grass. The wind scours it constantly, scrubbing the sage and sweeping out all the deserted buildings and weathered homes, cleaning out those that aren’t already bare. Flat as hell’s basement and empty as the boundless sky above it. The horizon makes as clean and slight a curve as if lathed by a master craftsman. Nothing is hidden.

Blurbworthiness: “Here comes Lions: a glittering dust storm, spinning every fantasy of the West, of small town America, together with the truth of a set of lives as real and precise as our own. Sweep us, up, Bonnie Nadzam, we are all yours.” (Ramona Ausubel, author of No One is Here Except All of Us)

Moonglow

by Michael Chabon

(Harper)

My typical six-word response when I get my hands on a new Michael Chabon novel: “Hello, boss? I’m calling in sick.”

Jacket Copy: The keeping of secrets and the telling of lies; sex and desire and ordinary love; existential doubt and model rocketry—all feature in the new novel from the author of The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay and The Yiddish Policeman’s Union. Moonglow unfolds as a deathbed confession. An old man, tongue loosened by powerful painkillers, memory stirred by the imminence of death, tells stories to his grandson, uncovering bits and pieces of a history long buried. From the Jewish slums of prewar South Philadelphia to the invasion of Germany, from a Florida retirement village to the penal utopia of a New York prison, from the heyday of the space program to the twilight of “the American Century,” Moonglow collapses an era into a single life and a lifetime into a single week. A lie that tells the truth, a work of fictional non-fiction, an autobiography wrapped in a novel disguised as a memoir, Moonglow is Chabon at his most daring and his most moving.

Opening Lines: This is how I heard the story. When Alger Hiss got out of prison, he had a hard time finding a job. He was a graduate of Harvard Law School, had clerked for Oliver Wendell Holmes and helped charter the United Nations, yet he was also a convicted perjurer and notorious as a tool of international communism. He had published a memoir, but it was dull stuff and no one wanted to read it. His wife had left him. He was broke and hopeless. In the end one of his remaining friends took pity on the bastard and pulled a string. Hiss was hired by a New York firm that manufactured and sold a kind of fancy barrette made from loops of piano wire. Feathercombs, Inc., had gotten off to a good start but had come under attack from a bigger competitor that copied its designs, infringed on its trademarks, and undercut its pricing. Sales had dwindled. Payroll was tight. In order to make room for Hiss, somebody had to be let go.

In an account of my grandfather’s arrest, in the Daily News for May 25, 1957, he is described by an unnamed coworker as “the quiet type.” To his fellow salesmen at Feathercombs, he was a homburg on the coat rack in the corner. He was the hardest-working but least effective member of the Feathercombs sales force. On his lunch breaks he holed up with a sandwich and the latest issue of Sky and Telescope or Aviation Week. It was known that he drove a Crosley, had a foreign-born wife and a teenage daughter and lived with them somewhere in deepest Bergen County. Before the day of his arrest, my grandfather had distinguished himself to his coworkers only twice. During Game 5 of the 1956 World Series, when the office radio failed, my grandfather had repaired it with a vacuum tube prized from the interior of the telephone switchboard. And a Feathercombs copywriter reported once bumping into my grandfather at the Paper Mill Playhouse in Millburn, where the foreign wife was, of all things, starring as Serafina in The Rose Tattoo. Beyond this nobody knew much about my grandfather, and that seemed to be the way he preferred it. People had long since given up trying to engage him in conversation. He had been known to smile but not to laugh. If he held political opinions—if he held opinions of any kind—they remained a mystery around the offices of Feathercombs, Inc. It was felt he could be fired without damage to morale.

Swimming Lessons

by Claire Fuller

(Tin House Books)

There are several mysteries at the heart of Claire Fuller’s second novel: Did the woman drown? If not, is she still alive and stalking her family? But if she did succumb to the waves, why did she leave messages on scraps of paper hidden inside books? I love novels that peel away layers gradually, like a literary onion, drawing readers deeper and deeper into the truth (or apparent truth). I can’t wait to start slicing into Swimming Lessons.

Jacket Copy: From the author of the award-winning and word-of-mouth sensation Our Endless Numbered Days comes an exhilarating literary mystery that will keep readers guessing until the final page. Ingrid Coleman writes letters to her husband Gil about the truth of their marriage, but instead of giving them to him, she hides each in the thousands of books he has collected over the years. When Ingrid has written her final letter she disappears from a Dorset beach, leaving behind her beautiful but dilapidated house by the sea, her husband, and her two daughters, Flora and Nan. Twelve years after her disappearance, Gil thinks he sees Ingrid from a bookshop window, but he’s getting older and this unlikely sighting is chalked up to senility. Flora, who has never believed her mother drowned, returns home to care for her father and to try to finally discover what happened to Ingrid. But what Flora doesn’t realize is that the answers to her questions are hidden in the books that surround her. Sexy and whip-smart, Swimming Lessons holds the Coleman family up to the light, exposing the mysterious and complicated truths of a passionate and troubled marriage.

Opening Lines: Gil Coleman looked down from the first-floor window of the bookshop and saw his dead wife standing on the pavement below.

Blurbworthiness: “Claire Fuller is a master of the psychological mystery. In her most recent novel, Swimming Lessons, no one is running around with a gun and no physical violence occurs. And yet damage happens. Families are cut to the bone. And lingering wounds are left festering into adulthood. This is a work that explores the very nature of forgiveness: how much should be forgiven before it becomes a burden, or before it becomes a secret life inside you until you can’t even forgive yourself? It’s a deliciously written story within a story that isn’t over until the last page has been turned.” (Pam Cady, University Book Store)

Labels:

Fresh Ink,

Front Porch Books,

Joyce Carol Oates,

short stories

Wednesday, April 27, 2016

Front Porch Books: April 2016 edition

Front Porch Books is a monthly tally of books—mainly advance review copies (aka “uncorrected proofs” and “galleys”)—I’ve received from publishers, but also sprinkled with packages from Book Mooch, independent bookstores, Amazon and other sources. Because my dear friends, Mr. FedEx and Mrs. UPS, leave them with a doorbell-and-dash method of delivery, I call them my Front Porch Books. In this digital age, ARCs are also beamed to the doorstep of my Kindle via NetGalley and Edelweiss. Note: many of these books won’t be released for another 2-6 months; I’m here to pique your interest and stock your wish lists. Cover art and opening lines may change before the book is finally released. I should also mention that, in nearly every case, I haven’t had a chance to read these books.

Constellation

by Adrien Bosc

(Other Press)

Part coroner’s report, part high drama involving multiple characters, part poetic meditation on fate and circumstance, Adrien Bosc’s debut novel about a 1949 plane crash fascinates me and I can’t stop staring at it from its place at the top of the To-Be-Read stack. I’ll admit I’ve been attracted to soap-operas-on-planes ever since I saw the 1970 movie Airport based on Arthur Hailey’s novel. All those various lives confined in a small metal tube that’s headed for disaster—who couldn’t find something to love about that? I’ll be ready to board Bosc’s short novel soon.

Jacket Copy: On October 27, 1949, Air France’s new plane, the Constellation, launched by the extravagant Howard Hughes, welcomed thirty-eight passengers aboard. On October 28, no longer responding to air traffic controllers, the plane disappeared while trying to land on the island of Santa Maria, in the Azores. No one survived. The question Adrien Bosc’s novel asks is not so much how, but why? What were the series of tiny incidents that, in sequence, propelled the plane toward Redondo Mountain? And who were the passengers? As we recognize Marcel Cerdan, the famous boxer and lover of Edith Piaf, and we remember the musical prodigy Ginette Neveu, whose tattered violin would be found years later, the author ties together their destinies: “Hear the dead, write their small legend, and offer to these thirty-eight men and women, like so many constellations, a life and a story.”

Blurbworthiness: “Sublime, haunting, exuberant, Constellation turns a tragedy into a miracle. In reviving the victims of a doomed 1949 Air France flight, Adrien Bosc writes beautifully about coincidence and fate, including the greatest coincidence at all—that we are alive on earth together for a short time. Constellation is a novel of profound humanity.” (Nathaniel Rich, author of Odds Against Tomorrow)

Unpleasantries

by Frank Soos

(University of Washington Press)

Full disclosure: Frank Soos is a good friend of mine. In fact, he’s a little more than that: he’s my mentor and the one writing instructor I can point to in my life and say, “That man there? He was my guidepost, my mile marker, my billboard that promised the relief of food and gas at the next exit.” Frank was my professor at the University of Alaska-Fairbanks and I owe a great deal of what comes out on my pages to his wisdom and encouragement. That being said, I look forward to Frank’s books enthusiastically and without bias. Though their appearances are often few and far between, Frank’s stories and essays are dependably thoughtful and rich in imagery. This new collection of essays is subtitled “Considerations of Difficult Questions,” but for me, there’s no question I’ll be digging into this book very, very soon.

Jacket Copy: Even from upside-down in his recently flipped truck, Frank Soos reveals himself to be ruminative, grappling with the limitations of language to express the human condition. Moving quickly―skiing in the dark or taking long summer bike rides on Alaska highways―Soos combines an active physical life with a dark and difficult interior existence, wrestling the full span of “thinking and doing” onto the page with surprising lightness. His meditations move from fly-fishing in dangerously swift Alaska rivers to memories of the liars and dirty-joke tellers of his small-town Virginia childhood, revealing insights in new encounters and old preoccupations. Soos writes about pain and despair, aging, his divorce, his father’s passing, regret, the loss of home, and the fear of death. But in the process of confronting these dark topics, he is full of wonder. As he writes at the end of an account of almost drowning, “Bruised but whole, I was alive, alive, alive.”

Opening Lines: It is dark outside. I’m alone in the ski hut, adding layer on layer to my ski clothes. Though some trails at the university in Fairbanks are lighted, I will take the longer, darker path through the woods. The last thing I do is strap on my headlamp, feeding the battery pack down my back under all my clothes so it will stay warm next to my skin. This may be crazy, setting out alone when it is already twenty below. But I know these trails so well that when I cannot sleep one of my tricks to overcome insomnia is to ski them in my mind.

Blurbworthiness: “What is a successful life, a life worthy of the improbable gift of consciousness? And how does one maintain courage and purpose under the shadow of mortality? These are the difficult questions that Frank Soos ponders most intently in these lucid, candid, witty essays. Whatever thread he follows―fishing, lying, playing basketball, telling jokes, building a canoe, rolling a truck, watching his father die―it leads him to reflect on the finiteness and preciousness of life.” (Scott Russell Sanders, author of Earth Works: Selected Essays)

Eleven Hours

by Pamela Erens

(Tin House Books)

As Publishers Weekly notes, labor and childbirth stories are as old as Eve delivering Cain, but in the hands of the exceptionally-talented Pamela Erens, Eleven Hours—a slim novel that will take you less than the titular time to read—promises to be a fresh take on OB-GYN.

Jacket Copy: From the critically acclaimed author of The Virgins, Eleven Hours is an intimate exploration of the physical and mental challenges of childbirth, told with unremitting suspense and astonishing beauty. Lore arrives at the hospital alone―no husband, no partner, no friends. Her birth plan is explicit: she wants no fetal monitor, no IV, no epidural. Franckline, a nurse in the maternity ward―herself on the verge of showing―is patient with the young woman. She knows what it’s like to worry that something might go wrong, and she understands the distress when it does. She knows as well as anyone the severe challenge of childbirth, what it does to the mind and the body. Eleven Hours is the story of two soon-to-be mothers who, in the midst of a difficult labor, are forced to reckon with their pasts and re-create their futures. Lore must disentangle herself from a love triangle; Franckline must move beyond past traumas to accept the life that’s waiting for her. Pamela Erens moves seamlessly between their begrudging partnership and the memories evoked by so intense an experience: for Lore, of the father of her child and her former best friend; for Franckline, of the family in Haiti from which she’s exiled. At turns urgent and lyrical, Erens’s novel is a visceral portrait of childbirth, and a vivid rendering of the way we approach motherhood―with fear and joy, anguish and awe.

Opening Lines: No, the girl says, she will not wear the fetal monitoring belt. Her birth plan says no to fetal monitoring.

These girls with their birth plans, thinks Franckline, as if much of anything about a birth can be planned. She thinks girl although she has read on the intake form that Lore Tannenbaum is thirty-one-years old, a year older than Franckline herself. Caucasian, born July something, employed by the New York City Department of Education. Franckline pronounced the girl’s name wrong at first, said “Lorie,” and the girl corrected her, said there was only one syllable. Lore.

Blurbworthiness: “Written with incredible clarity, the third novel from Erens is a wonder, shifting between two protagonists with ease to tell a deeply personal narrative of childbirth, complete with tension, horror, and deep mature emotion. This novel does not sentimentalize the delivery of a child, but rather examines the surprise—mental and physical—that accompanies it. Labor stories are as old as time, but Erens’s novel feels incredibly fresh and vivid. An outstanding accomplishment.” (Publishers Weekly)

The Stopped Heart

by Julie Myerson

(Harper Perennial)

There are first lines, and then there are first lines. I defy anyone to read the opening paragraph of Julie Myerson’s new novel and put the book aside with a shrug and a “ho-hum.” The remainder of The Stopped Heart promises to do the opposite of its title, too. My heart’s already racing from that first page alone.

Jacket Copy: Mary Coles and her husband, Graham, have just moved to a cottage on the edge of a small village. The house hasn’t been lived in for years, but they are drawn to its original features and surprisingly large garden, which stretches down into a beautiful apple orchard. It’s idyllic, remote, picturesque: exactly what they need to put the horror of the past behind them. One hundred and fifty years earlier, a huge oak tree was felled in front of the cottage during a raging storm. Beneath it lies a young man with a shock of red hair, presumed dead—surely no one could survive such an accident. But the red-haired man is alive, and after a brief convalescence is taken in by the family living in the cottage and put to work in the fields. The children all love him, but the eldest daughter, Eliza, has her reservations. There’s something about the red-haired man that sits ill with her. A presence. An evil. Back in the present, weeks after moving to the cottage and still drowning beneath the weight of insurmountable grief, Mary Coles starts to sense there’s something in the house. Children’s whispers, footsteps from above, half-caught glimpses of figures in the garden. A young man with a shock of red hair wandering through the orchard. Has Mary’s grief turned to madness? Or have the events that took place so long ago finally come back to haunt her?

Opening Lines: It was a sunny day. The sky was thick and high and blue. Addie Sands was standing in the lane and she was screaming. There was blood everywhere. On her skirts, her wrists, her face. A dark hole where her mouth should be. There were no words. Nothing but the black taste of her screaming.

Mercury

by Margot Livesey

(Harper)

A horse, an optometrist’s wife, an obsession: Margot Livesey’s new novel stirs these disparate ingredients into a story that sets a fishhook deep in my attention span, pulling me closer and closer with every page. Mercury is shaping up to be one of the most intriguing books on the 2016 Fall list.

Jacket Copy: Donald believes he knows all there is to know about seeing. An optician in suburban Boston, he rests assured that he and his wife, Viv, who works at the local stables, will live out quiet lives with their two children. Then Mercury—a gorgeous young racehorse—enters their lives and everything changes. Viv’s friend Hilary has inherited Mercury from her brother after his mysterious death—he was riding Mercury late one afternoon and the horse returned to the stables alone. When Hilary first brings Mercury to board at the stables everyone there is struck by his beauty and prowess, particularly Viv. As she rides him, Viv dreams of competing with Mercury, rebuilding the ambitions of grandeur that she held for herself before moving to the suburbs. But her daydreams soon morph into consuming desire, and her infatuation with the thoroughbred quickly escalates to obsession. By the time Donald understands the change that has come over Viv, it is too late to stop the impending fate that both their actions have wrought for them and their loved ones. A beautifully crafted, riveting novel about the ways in which relationships can be disrupted and, ultimately, destroyed by obsession, secrets and ever-escalating lies.

Opening Lines: My mother called me after a favorite uncle, who was in turn called after a Scottish king. Donald III was sixty when he first ascended the throne in 1093. He went on to reign twice, briefly and disastrously. As a child I hated my name—other children sang “Donald, where’s y’er troosers?” in the playground—but as an adult I have come to appreciate being named after a valiant late bloomer: a man who seized the day. Of course most Americans, when I introduce myself, are thinking not about Scottish history but about a cartoon duck.

Blurbworthiness: “Mercury demonstrates Tolstoy’s dictum: all unhappy families are unhappy in their own way. The Stevensons find themselves upended by a horse—a magnificent horse that sets off a chain of deceit and crime. This powerful novel reveals the fragility of life when tested by the shock of genuine passion.” (Ben Fountain, author of Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk)

In Sunlight or In Shadow: Stories Inspired by the Paintings of Edward Hopper

edited by Lawrence Block

(Pegasus)

If ever there were a painter perfectly primed to have an anthology of stories inspired by his or her canvases, then Edward Hopper surely fits the bill. In Sunlight or In Shadow promises to be a remarkable collection of fiction, not only for the outstanding lineup of contributors but for the source inspiration as well. As editor Lawrence Block says in his Foreword, “Hopper was neither an illustrator nor a narrative painter. His paintings don’t tell stories. What they do is suggest—powerfully, irresistibly—that there are stories within them, waiting to be told. He shows us a moment in time, arrayed on a canvas; there’s clearly a past and a future, but it’s our task to find it for ourselves.”

Jacket Copy: Lawrence Block has invited seventeen outstanding writers to join him in an unprecedented anthology of brand-new stories: In Sunlight or In Shadow. The results are remarkable and range across all genres, wedding literary excellence to storytelling savvy. Contributors include Stephen King, Joyce Carol Oates, Robert Olen Butler, Michael Connelly, Megan Abbott, Craig Ferguson, Nicholas Christopher, Jill D. Block, Joe R. Lansdale, Justin Scott, Kristine Kathryn Rusch, Warren Moore, Jonathan Santlofer, Jeffery Deaver, Lee Child, and Lawrence Block himself. Even Gail Levin, Hopper’s biographer and compiler of his catalogue raisonée, appears with her own first work of fiction, providing a true account of art theft on a grand scale and told in the voice of the country preacher who perpetrated the crime. In a beautifully produced anthology as befits such a collection of acclaimed authors, each story is illustrated with a quality full-color reproduction of the painting that inspired it. Illustrated with 17 full color plates, one for each chapter.

Opening Lines: “She went udders out.”

“No pasties even?”

“Like a pair of traffic lights.”

Pauline hears them on the porch. Bud is telling her husband about a trip to New York City a few years ago. Going to the Casino de Paree.

Her husband says almost nothing, smoking cigarette after cigarette and making sure Bud always has a Blatz in hand from the metal cooler beside him.

(from “Girlie Show” by Megan Abbott)

Remarkable

by Dinah Cox

(BOA Editions)

Short Story Month begins in a few days and I can’t think of a better way to get things underway than this collection of short fiction by Dinah Cox. Midwestern stories hold a special fascination for me—perhaps because I grew up in Wyoming and now live in Montana—and these tales set mostly in Oklahoma seem to be especially full of Great Plains goodness.

Jacket Copy: Set within the resilient Great Plains, these award-winning stories are marked by the region’s people and landscape, and the distinctive way it is both regressive in its politics yet also stumbling toward something better. While not all stories are explicitly set in Oklahoma, the state is almost a character that is neither protagonist nor antagonist, but instead the weird next-door-neighbor you’re perhaps too ashamed of to take anywhere. Who is the embarrassing one—you or Oklahoma?

Opening Lines: A guy walks into Kentucky Fried Chicken and says, Gimme some chicken. Maybe he has a gun and maybe he has only his finger, shaking and sweating underneath the front flap of his jacket; either way, his demand is not for money but chicken. Two piece leg and thigh. Extra crispy. No one in his right mind asks for original recipe these days. And that biscuit had better be hot, don’t give him any of that hockey puck shit. Everyone is worried. Once, exactly a year ago today, a tornado ripped through town and blew out the restaurant’s front windows. Customers, clerks, managers, babies, and dead frozen chickens all huddle in the walk-in for safety. No one was hurt. But today is a different story. If the man with the gun/finger doesn’t get his chicken, he might shoot someone. He might kill someone.

“To go,” he says. “Didn’t I say to go earlier? I think I did.”

“You did, sir,” says the clerk. “Sorry.”

“Damn right you’re sorry.”

This is where the story begins and also where the story ends, because the guy took his chicken and left the store. Just walked right out. And no one called the police and no one posted about it on Facebook and no one tweeted or bleated or cared. The register didn’t even come up short because no money changed hands. But the best part of the story is that it at once represents what’s best about small towns and what’s worst about them. What’s best is that people in small towns will give one another chicken. For free. What’s worst is the tornado’s near miss, the broken glass all over the greasy floor, the children crying, the dead chickens in the freezer, and the people who want nothing more than to eat them.

Blurbworthiness: “Funny, disturbing, and unapologetically smart—the stories in Remarkable sneak into your heart and then break it. We meet Marcella who works at the Telephone Museum and hears imaginary conversations, and the B-movie star of Tumbleweed Town, a sort of Brokeback Mountain meets Deliverance meets The Monkees. The fictive people in this collection, iconoclasts of the Midwest, conjure their own idiosyncratic, surprisingly honest and tender worlds.” (Nona Caspers, author of Heavier than Air)

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)