Front Porch Books is a

monthly tally of books--mainly advance review copies (aka "uncorrected proofs"

and "galleys")--I've received from publishers, but also sprinkled with packages

from Book Mooch, Amazon and

other sources. Because my dear friends, Mr. FedEx and Mrs. UPS, leave them with

a doorbell-and-dash method of delivery, I call them my Front Porch Books. In

this digital age, ARCs are also beamed to the doorstep of my Kindle via NetGalley and Edelweiss. Note: most of these books won't be released for another 2-6 months; I'm just

here to pique your interest and stock your wish lists. Cover art and opening

lines may change before the book is finally released.

Donnybrook by Frank Bill (

Farrar, Straus and Giroux): When it comes to grit-lit, there's no one giving Donald Ray Pollock and Chuck Palahniuk a run for their money more than Frank Bill. His debut collection of short stories,

Crimes in Southern Indiana, smashed readers with a right hook as powerful as the one pictured on the cover of his first novel,

Donnybrook. You'll notice that fist has no glove. That's how Bill writes:

smack! smack! smack! without letting up. Wrack and ruin. Drugs, sex, blood. These pages aren't for the timid.

Jacket Copy:

The Donnybrook is a three-day bare-knuckle tournament held on a thousand-acre

plot out in the sticks of southern Indiana. Twenty fighters. One

wire-fence ring. Fight until only one man is left standing while a rowdy

festival of onlookers—drunk and high on whatever’s on offer—bet on the

fighters. Jarhead is a desperate man who’d do just about anything to

feed his children. He’s also the toughest fighter in southeastern Kentucky, and

he’s convinced that his ticket to a better life is one last fight with a cash

prize so big it’ll solve all his problems. Meanwhile, there’s Chainsaw

Angus—an undefeated master fighter who isn’t too keen on getting his face

punched anymore, so he and his sister, Liz, have started cooking meth. And they

get in deep. So deep that Liz wants it all for herself, and she might just

be ready to kill her brother for it. One more showdown to take place at

the Donnybrook.

Sure, there are a lot of characters, but I'm wagering that Bill can make each one of them stand out in their own nasty-tender way.

The Thief of Auschwitz by Jon Clinch (

Unmediated Ink): You may not recognize the publisher of Clinch's new novel (his fourth, after

Finn,

Kings of the Earth, and the pseudonymously-published science fiction novel called

What Came After). That's because it's a new imprint started by Clinch himself (I'm bucking tradition here to highlight a self-published book, but I'm fascinated by this novel's premise and Clinch's chutzpah in breaking away from a traditional publishing route). Though his first two novels were published by Random House, Clinch decided to take the steering wheel in his own hands this time.

At his blog, he wrote:

(W)e’re on the cusp of some kind of revolution, right here and right now. I’ve never been much of a revolutionary, myself. To tell the whole truth—and you can see this in my work—I’m a traditionalist. A believer that the old values and the tested principles and the enduring systems remain the best. It meant a lot to me to be published by Random House, for example. It meant even more for one of my books to be named a Notable Book by the American Library Association. And seeing my work in my favorite indie bookstores remains a thrill. But I’ve always been self-reliant, and I’ve always gone pretty much my own way. So I suppose that if anyone was well-suited to tossing aside the conventions of big literary publishing and going it alone, I made a pretty fair candidate.

For more on his long path toward publishing his first novel,

Finn, I encourage you to read the account at the end of his

Readers Guide (pdf) to his latest book. Clinch's ballsy independence prompted

Washington Post book critic Ron Charles to write: "Traditional book publishing hasn’t collapsed yet, but you can see signs of

erosion everywhere." Striking off on a new path is all well and good, but for me, the proof is in the pudding. To my delight, after receiving an advance copy of

The Thief of Auschwitz, I found it was a very tasty pudding indeed. I was immediately drawn in by the

Opening Lines:

The camp at Auschwitz took one year of my life, and of my own free will I gave it another four.

This was 1942. I was fourteen years old but tall for my age, and I’d spent a lot of time outdoors, so I lied and I got away with it. My father and I passed through that barbed wire gate and presto, I was eighteen. It was his idea, and if I hadn’t followed through on it they’d have been done with me in an hour, not a year. Maybe less than that. I was just a boy, after all. I was too young to be of any use.

Here's the

Jacket Copy:

Told in two intertwining narratives, The Thief of Auschwitz takes readers on a dual journey: one into the death camp at Auschwitz with Jacob, Eidel, Max, and Lydia Rosen; the other into the heart of Max himself, now an aged but extremely vital—and outspoken—survivor. Max is a world-renowned painter, and he’s about to be honored with a retrospective at the National Gallery in Washington. The truth, though, is that he’s been keeping a crucial secret from the art world—indeed from the world at large, and perhaps even from himself—all his life long.

As with any of the titles I spotlight at Front Porch Books, I'll reserve complete judgment until after I've had a chance to read the whole thing, but for now I hope your curiosity is as piqued as mine and that you'll order a copy of Clinch's daring new novel.

Life Form by Amelie Nothomb (

Europa Editions): Belgian writer Amelie Nothomb is not exactly a household name in the U.S. (at least not in

my household), but that could change with the publication of her nineteenth novel. It's a slim book with a fascinating, topical subject matter at its heart. Just take a look at the

Jacket Copy:

One morning, the heroine of this book, a well-known author named Amélie Nothomb, receives a letter from one of her readers--an American soldier stationed in Iraq by the name of Melvin Mapple. Horrified by the endless violence around him, Melvin takes comfort in over-eating. He eats and eats until his fat starts to suffocate him and he can barely fit into his XXXXL clothes. Disgusted with himself, but unable to control his eating, he takes his mind off his ever-growing bulk by naming it Scheherazade and pretending that his own flesh will keep an increasingly intolerable loneliness at bay. Repulsed but also fascinated, Nothomb begins an exchange with Mapple. She finds herself opening up to him about her difficulties with being in the public spotlight and the challenges of her work.An epistolary friendship of sorts develops, one that delves into universal questions about human relationships, one with an unexpected (to say the least!) final twist.

Here are the

Opening Lines to this small-but-astounding novel:

That morning I received a new sort of letter:

Baghdad, December 18, 2008

Dear Amelie Nothomb,

I'm a private in the US Army, my name is Melvin Mapple, you can call me Mel. I've been posted in Baghdad ever since the beginning of this fucking war, over six years ago. I'm writing to you because I am as down as a dog. I need some understanding and I know that if anyone can understand me, you can.

Please answer. I hope to hear from you soon.

Melvin Mapple

At first I thought this was some sort of hoax. Even if Melvin Mapple did exist, what right did he have to speak to me like that? Wasn't there some sort of military censorship to prevent words like "fucking" from being used in conjunction with "war"?

So there you have it: straightforward, witty and intriguing. I can hardly wait to read the other 124 pages.

We Live in Water by Jess Walter (

Harper Perennial): They tell us short story collections don't sell. When I say "us," I mean writers; and when I say "they," I mean literary agents, editors, and prognosticators of the coming collapse of the publishing industry. But I happen to believe that short-form fiction is very much alive and, in some cases, thriving. (Want proof of life? For starters, check out Larry Dark's excellent blog for

The Story Prize.) If anyone can make a successful run at proving "them" wrong, it's Jess Walter. Fresh on the heels of this year's critically-acclaimed novel

Beautiful Ruins,

We Live in Water is Walter's first short story collection and it looks as good as everything we've come to expect from Walter. According to the

Jacket Copy, these stories "veer from comic tales of love to social satire to suspenseful crime fiction, from hip Portland to once-hip Seattle to never-hip Spokane, from a condemned casino in Las Vegas to a bottomless lake in the dark woods of Idaho. This is a world of lost fathers and redemptive con men, of meth tweakers on desperate odysseys and men committing suicide by fishing." Here are the

Opening Lines from the title story, which originally appeared at

Byliner:

Oren Dessens leaned forward as he drove, perched on the wheel, cigarette in the corner of his mouth, open can of beer between his knees. He’d come apart before, a couple three times, maybe more, depending on how you counted. The way Katie figured—every fistfight and whore, every poker game and long drunk—he was always coming apart, but Oren didn’t think it was fair to count like his ex-wife did. Up to him, he’d only count those times he was in real danger of not coming back.

I had the pleasure of hearing Walter read the collection's final story, "Statistical Abstract For My Hometown of Spokane, Washington," at this year's

Montana Festival of the Book. Believe me when I tell you it was nothing short of an incredible magic trick, as if Walter was standing up there at the front of the room, sawing a story in half, splitting it apart with finesse, keeping us spellbound and breath-held, then putting it back together again with a final, devastating sentence that even had the author choking up. We all left the room shaking our heads and saying to ourselves, "How did he do that?"

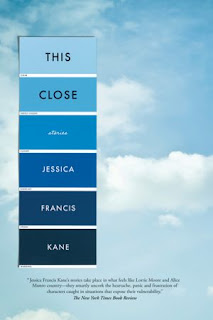

This Close by Jessica Francis Kane (

Graywolf Press): The title of Kane's debut collection of short stories makes me think of a man squinting, holding up two fingers just micro-millimeters apart.

This close. Judging by what I've read of the book so far, I'd say that the gentleman should go ahead and press those fingers together because Kane isn't just close, she's all the way

there. She's a generous storyteller--by that, I mean she doesn't write in spare, minimalist prose. She gives readers full, rich portraits of her characters and their worlds, even in the shortest of stories. Here are the

Opening Lines to "Lucky Boy," the first story in the book:

Something about New York City makes a lot of people understand you should try to

look your best. Tourists, for example, often wear brand-new shoes and socks. They buy them after they arrive, I think, probably spending more than they should. When they step off a curb or into a cab, you sometimes see a flash of their unscuffed soles, the socks fresh and fitted. Recently I was buying a pair of new shoes myself when I heard another man in the shop proudly decline to take his old shoes with him. "No," he said, pointing to the store entrance, a determined look in his eye. "I'm going to wear my New York shoes right out that door." New York shoes, indeed. He seemed ready for a fight.

I love how that last line propels us into the rest of the story, even if that new-shoes man never makes another appearance. I should also mention how much I love the cover design by Kyle G. Hunter. It's a stroke of genius to put the blue-paint sample strip up against a blue sky. Kudos to the Graywolf team for choosing this cover!

Blurbworthiness: "

This Close is timeless, humane, vulnerable, and compulsively readable. Jessica Francis Kane has a fierce, keen eye and a gentle, sure touch. I devoured this collection. More, please..." (Jennifer Gilmore, author of

Something Red)

The Annotated Brothers Grimm (The Bicentennial Edition) by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm, translated by Maria Tatar (

W. W. Norton): Just in time for holiday gift-giving, Norton trots out another sumptuous volume of classic literature, annotated with enriching notes and gorgeously illustrated. Norton is re-issuing this edition of Grimm fairy tales in honor of the 200th anniversary of the first publication of

Children's Stories and Household Tales.

The Annotated Brothers Grimm includes an introduction by A. S. Byatt, who writes: "This is the book I wanted as a child and didn't have." (For other great annotated books from the publisher, check out

The Annotated Wizard of Oz,

The Annotated Uncle Tom's Cabin and

The Annotated Christmas Carol) Though I'm a lukewarm fan of the contemporary

Grimm TV series and have more than a passing acquaintance with Disney-fied fables, I've never actually read the original tales from the Brothers Grimm. This thick, rich book will provide a perfect gateway into their world. Here's the

Jacket Copy from the publisher:

Publication of the Grimms’ Children’s Stories and Household Tales in 1812 brought the great European oral folk tradition into print for the first time. The Annotated Brothers Grimm returns in a deluxe and augmented 200th-anniversary edition commemorating that landmark event. Adding to such favorites as “Cinderella,” “Little Red Riding Hood,” “Snow White,” and “Rapunzel,” Maria Tatar includes six new entries, among them “Four Clever Brothers,” “The Water of Life,” “The White Snake,” and “The Old Man and His Grandson.” The expanded edition features an enhanced selection of illustrations, many in color, by legendary artists such as George Cruikshank and Arthur Rackham; annotations that explore the historical origins, cultural context, and psychological effects of the tales; and a biographical essay on Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm.

Opening Lines (from "The Frog King, or Iron Heinrich," the first story in the collection):

Once upon a time, when wishes still came true, there lived a king who had beautiful daughters. The youngest was so lovely that even the sun, which had seen so many things, was filled with wonder when it shone upon her face.

Woke Up Lonely by Fiona Maazel (

Graywolf Press): Maazel's 2008 novel

Last Last Chance ranks high among the many critically-acclaimed unread books in my library. So many books, so little time....You know how it goes. Maazel's new novel is enough to make me give

Last Last Chance one more chance. Here's the

Jacket Copy:

Thurlow Dan is the founder of the Helix, a cult that promises to cure loneliness

in the twenty-first century. With its communes and speed-dating, mixers and

confession sessions, the Helix has become a national phenomenon—and attracted

the attention of governments worldwide. But Thurlow, camped out in his

Cincinnati headquarters, is lonely—for his ex-wife, Esme, and their daughter,

whom he hasn't seen in ten years.

Esme, for her part, is a covert agent who has spent her life spying on

Thurlow, mostly to protect him from the law. Now, with her superiors demanding

results, she recruits four misfits to botch a reconnaissance mission in

Cincinnati. But when Thurlow takes them hostage, he ignites a siege of the Helix

House that will change all their lives forever. With fiery, exuberant prose, Fiona Maazel takes us on a wild ride through

North Korea's guarded interior and a city of vice beneath Cincinnati, a ride

that twists and turns as it delves into an unsettled, off-kilter America.

Woke Up Lonely is an original and deeply funny novel that explores our

very human impulse to seek and repel intimacy with the people who matter to us

most.

I particularly like the

Opening Lines for their fragmentary, stop-and-stutter rhythm which serves to pull me into Thurlow's story:

They were together. In their way. Dad on a bus, gaping out the window at a little girl and her mom. The pair not five feet away. He swiped the glass with his palm. Stop the bus, he said, though no one heard him. Stop the bus. His wife and daughter tromped through the snow. His wife? His ex-wife, bundled in down, soldiering on. His daughter, whom he had not seen in nine of her ten years. She jumped a puddle of slush. Wore a hat with braided tassels. He told himself to get up. Get up, Thurlow. But he couldn't. He was stuck being someone else. A man to whom life had become a matter of seconds, to whom a bus was the universe, and the instinct to watch, all that there was to being in love.

The Burn Palace by Stephen Dobyns (

Blue Rider Press): Dobyns is another of those writers who has a huge following but mostly flies under the radar. He's certainly flown "nap of the earth" (to use a military pilot's term) below my radar. I have a few of his more than thirty published books (ranging from novels to poetry collections), but they remain unread. All that could change with his newest novel,

The Burn Palace. Take a gander at the

Jacket Copy and tell me if you, too, aren't hooked:

At two-thirty in the morning at the local hospital in the small town of Brewster, Rhode Island, Alice Alessio--also known as Nurse Spandex--is given the surprise of her life. Coming back from a secret tryst with a doctor, she peeks in to check on the newborn baby she was supposed to be watching, and finds a huge, writhing red-and-yellow snake in the bassinet instead. So begins the series of strange and disturbing events that start to plague this sleepy little community and confound the police. Woody Potter, the detective on the case, simply can't put it all together: What is the thread that connects a missing baby, a dead insurance investigator, and a local Wiccan sect? Why do all roads seem to lead to the town yoga center? And what exactly is going on with Carl Krause, the local man who works at the funeral home, who has taken to growling at his neighbors?

Want more? Okay, here are the

Opening Lines:

Nurse Spandex was late, and as she broke into a run her rubber-soled clogs went squeak-squeak on the floor of the hallway leading to labor and delivery. It was two-thirty on a Thursday morning, and if Tabby Roberts--Tabitha, she called her to her face, because she'd never liked the head nurse--ever learned she had left those two babies alone, she'd be royally screwed, which made her laugh because that was why she was late, she had been getting royally screwed back in 217, where that poor colored woman had died in the afternoon. That's where Dr. Balfour had pushed her, and that's where she'd gone--to a bed stripped of sheets and pads--because she'd worked hard to get Dr. Balfour motivated and once she got him unzipping his fly, she wasn't going to complain where he took her; she let him screw her in the toilet since that's what he wanted, like Dr. Stone last March, but then Dr. Stone took a job at Providence Hospital and so nothing had come of it except a few teary phone calls with her doing the crying, but it didn't do any good because Dr. Stone had stayed where he was.

The writhing snake shows up just a few paragraph later and starts Nurse Spandex on a screaming jag--"a high, awful noise she'd never made before," and she "kept screaming like she meant to shatter glass." Yes indeed, I've grabbed the lure between my teeth and I'm being pulled to shore.

Revenge: Eleven Dark Tales by Yoko Ogawa, translated by Stephen Snyder (

Picador): In keeping with the creepy chill of suspense fiction, here's a new collection of short stories which, by the looks of it, can scare the color right out of your hair.

Jacket Copy:

An aspiring writer moves into a new apartment and discovers that her landlady has murdered her husband. Elsewhere, an accomplished surgeon is approached by a cabaret singer, whose beautiful appearance belies the grotesque condition of her heart. And while the surgeon’s jealous lover vows to kill him, a violent envy also stirs in the soul of a lonely craftsman. Desire meets with impulse and erupts, attracting the attention of the surgeon’s neighbor---who is drawn to a decaying residence that is now home to instruments of human torture. Murderers and mourners, mothers and children, lovers and innocent bystanders---their fates converge in an ominous and darkly beautiful web.

Here are the

Opening Lines to the first story in the book, "Afternoon at the Bakery." The imagery is beautiful but you just know something dark is lurking beneath the surface of all that sunny light:

It was a beautiful Sunday. The sky was a cloudless dome of sunlight. Out on the square, leaves fluttered in a gentle breeze along the pavement. Everything seemed to glimmer with a faint luminescence: the roof of the ice-cream stand, the faucet on the drinking fountain, the eyes of a stray cat, even the base of the clock tower covered with pigeon droppings.

Families and tourists strolled through the square, enjoying the weekend. Squeaky sounds could be heard from a man off in the corner, who was twisting balloon animals. A circle of children watched him, entranced. Nearby, a woman sat on a bench knitting. Somewhere a horn sounded. A flock of pigeons burst into the air, and startled a baby who began to cry. The mother hurried over to gather the child in her arms.

You could gaze at this perfect picture all day—an afternoon bathed in light and comfort—and perhaps never notice a single detail out of place, or missing.

Blurbworthiness: “Yoko Ogawa is an absolute master of the Gothic at its most beautiful and

dangerous, and

Revenge is a collection that deepens and darkens with every story

you read.” (Peter Straub)

Y by Marjorie Celona (

Free Press): From the beautiful cover design to the intriguing plot synopsis, this debut novel has me saying "

Yes!" Here's the

Jacket Copy:

Marjorie Celona’s exquisitely rendered debut is about a

wise-beyond-her-years foster child abandoned as a newborn on the doorstep of the

local YMCA. Swaddled in a dirty gray sweatshirt with nothing but a Swiss Army

knife tucked between her feet, little Shannon is discovered by a man who catches

only a glimpse of her troubled mother as she disappears from view. That morning,

all three lives are forever changed.

Bounced between foster homes, Shannon endures abuse and neglect until she

finally finds stability with Miranda, a kind but no-nonsense single mother with

a free-spirited daughter of her own. Yet Shannon defines life on her own terms,

refusing to settle down, and never stops longing to uncover her roots—especially

the stubborn question of why her mother would abandon her on the day she was

born.

Brilliantly and hauntingly interwoven with Shannon’s story is the tale of her

mother, Yula, a girl herself who is facing a desperate fate in the hours and

days leading up to Shannon’s birth. As past and present converge, Y tells

an unforgettable story of identity, inheritance, and, ultimately, forgiveness.

I'm going to give you two sets of

Opening Lines--the "author's note" which opens the book with a beautiful brushstroke of lyrical prose, and the first two paragraphs of Chapter 1. I think you'll agree that there's some first-rate writing on these pages....

Y

That perfect letter. The wishbone, fork in the road, empty wineglass. The question we ask over and over. Why? Me with my arms outstretched, feet in first position. The chromosome half of us don’t have. Second to last in the alphabet: almost there. Coupled with an L, let’s make an adverb. A modest X, legs closed. Y or N? Yes, of course. Upside-down peace sign. Little bird tracks in the sand.

Y, a Greek letter, joined the Latin alphabet after the Romans conquered Greece in the first century—a double agent: consonant and vowel. No one used adverbs before then, and no one was happy.

* * *

My life begins at the Y. I am born and left in front of the glass doors, and even though the sign is flipped “Closed,” a man is waiting in the parking lot and he sees it all: my mother, a woman in navy coveralls, emerges from behind Christ Church Cathedral with a bundle wrapped in gray, her body bent in the cold wet wind of the summer morning. Her mouth is open as if she is screaming, but there is no sound here, just the calls of birds. The wind gusts and her coveralls blow back from her body, so that the man can see the outline of her skinny legs and distended belly as she walks toward him, the tops of her brown workman’s boots. Her coveralls are stained with motor oil, her boots far too big. She is a small, fine-boned woman, with shoulders so broad that at first the man thinks he is looking at a boy. She has deep brown hair tied back in a bun and wild, moon-gray eyes.

There is a coarse, masculine look to her face, a meanness. Even in the chill, her brow is beaded with sweat. The man watches her stop at the entrance to the parking lot and wrench back her head to look at the sky. She is thinking. Her eyes are wide with determination and fear. She takes a step forward and looks around her. The street is full of pink and gold light from the sun, and the scream of a seaplane comes fast overhead, and the wet of last night’s rain is still present on the street, on the sidewalk, on the buildings’ reflective glass. My mother listens to the plane, to the birds. If anyone sees her, she will lose her nerve. She looks up again, and the morning sky is as blue as a peacock feather.

My Ideal Bookshelf, edited by Thessaly La Force, art by Jane Mount (

Little, Brown and Co.): This has been the year of books celebrating books. In just the past twelve months, we've seen

Read This!: Handpicked Favorites from America's Indie Bookstores;

My Bookstore: Writers Celebrate Their Favorite Places to Browse, Read, and Shop;

Weird Things Customers Say in Bookstores; Joe Queenan's

One for the Books;

Books to Die For: The World's Greatest Mystery Writers on the World's Greatest Mystery Novels;

Judging a Book by Its Lover: A Field Guide to the Hearts and Minds of Readers Everywhere; and Robin Sloan's highly-praised novel

Mr. Penumbra's 24-Hour Bookstore. Whether it's a case of synchronicity or a universal

cri de coeur against the shuttering of independent bookstores, it seems everyone wants to convince readers to keep on reading. Because, let's face it, that's who's buying these books about books: die-hard bibliophiles who yearn for that warm-maple-syrup-in-the-throat feeling of nostalgia for well-loved books.

My Ideal Bookshelf is, first and foremost, a love letter to those treasured volumes many of us have on our own shelves. Contributors share their own favorite books which are illustrated by paintings of their spines-out shelf. It's artfully designed and would be ideal for your coffee table. You could, you know, casually place it there where your boorish brother-in-law normally puts his feet as he watches Monday Night Football and spills potato chip crumbs all over your couch. Maybe, you think, just maybe you can catch his attention and get him interested in books (it will help if you keep the book open to contributor Tony Hawk's ideal bookshelf where the skateboarder lists everything from Lance Armstrong's

It's Not About the Bike to Nick Hornby's

High Fidelity). In their preface to the book, editor Thessaly La Force and artist Jane Mount describe the assignment they gave more than one hundred creative people (chefs and architects, writers and fashion designers, filmmakers and ballet dancers): “Select a small shelf of books that represent you—the books that have changed your life, that have made you who you are today, your favorite favorites.” Not an easy task for anyone, but the results in this 200-page book span a satisfying range of literature--from

Middlemarch (selected by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie) to the Hardy Boys'

The Secret of the Old Mill (selected by William Wegman). If you're looking for the perfect gift to buy a book lover (or even a Pringles-munching sportsfan), I could think of no finer book to put under the Christmas tree. To give you a taste of what's inside this vibrant album of book spines, here's David Sedaris' shelf:

Add

Moby-Dick,

The Norton Anthology of Poetry and a couple of Charles Dickens novels and that would be close to my own ideal bookshelf. I love what Sedaris had to say in his accompanying remarks:

Tobias Wolff is America's greatest living short-story writer. Sometimes I meet ministers, and I always say to them, "If I had a church, I'd read a Tobias Wolff story every week, and then I'd say to people, 'Go home.'" There's nothing else you would need to say. Every story is a manual on how to be a good person, but without ever being preachy. They're deeply moral stories; the best of them read like parables.