When I sit in my favorite reading chair in December and think about all the books about to come my way over the next twelve months, there is, admittedly, a feeling both of dread and hope. I want my reading to be something I look forward to each day, a feeling of can't-wait-to-get-to-the-page. Sometimes the reading year turns out to have that kind of vibrancy....but there have been times when it seems every other book was heavy and dull as lead, the language uninspired and the characters flat.

Happily, 2014 was less dross and more gold. In fact, it turned out to be one of the best reading years I've had in a long time--particularly for first novels. Maybe I was just making better choices this year, or maybe the publishing stars were in full alignment. Whatever the reason, my Library Thing catalog was dominated by four- and five-star ratings this year.

Here are my favorite books published in 2014, in no particular order:

by Anthony Doerr

This was the year I vowed to read authors who'd been languishing in my To-Be-Read queue for far too long. I started with Donna Tartt (The Secret History--one of the best non-2014 books I read in the past twelve months), and moved on to Elizabeth Gaskell (North and South) before diving into a deep pool of Anthony Doerr. I couldn't have picked a better year to read my way through the Boise, Idaho writer's canon, because while Memory Wall and The Shell Collector were excellent examples of the short-story form, this year's novel All the Light We Cannot See proved to be his masterpiece. A simple plot synopsis—blind French girl and Hitler Youth boy communicate via radio during World War Two—doesn't do Doerr's novel justice. This is a 500-page page-turner whose story lives and breathes at the sentence level. Every word is a gem, placed with a pair of jeweler's tweezers into its place on the page. The result is a story as intricate as the model city M. LeBlanc builds for his daughter Marie-Laure. Just like that French locksmith, Anthony Doerr is a master craftsman. I can't wait to read his other two books: the novel About Grace and the memoir Four Seasons in Rome.

by Brian Turner

Near the end of this gut-honest memoir about poet Brian Turner’s time in Iraq, he writes: “America, vast and laid out from one ocean to another, is not a large enough space to contain the war each soldier brings home.” Likewise, this book and its 224 pages probably cannot hold all the rampaging emotions of Turner’s war experience, but damn if he doesn’t spill a lot of emotional blood in the course of these 136 short chapters. As anyone who has read Turner’s two collections of poetry (Here, Bullet and Phantom Noise) will tell you, he’s able to turn even the most horrific topics--death, dismemberment, sexual assault, post-traumatic nightmares--into things of linguistic beauty. In My Life as a Foreign Country, he once again brings the war home to us. Are we bold enough to hold his words?

by Victoria Wilson

Victoria Wilson spent 15 years deep-sea diving into Barbara Stanwyck's life. After I closed the 1,056th page of her book about actress Barbara Stanwyck, I wanted more, more, more! Specifically, I wanted to read more about Stanwyck because Wilson only covers the first third of the screen legend’s life. I’m praying that Volume 2 (which will begin right around the time Stanwyck is filming Frank Capra’s Meet John Doe) is on its way soon. We don’t often see a Hollywood biographer give the same kind of treatment to her subject like, say, Robert A. Caro devotes to his multi-volume look at Lyndon B. Johnson’s life; but Stanwyck seems to deserve it. She was a tough pioneer in the Golden Age of Tinseltown (she was the first actress under contract to two studios at the same time) and Wilson paints a rich, full-bodied portrait of a woman who once self-deprecatingly said, “I have the face that sank a thousand ships.” Maybe Stanwyck wasn’t the most conventionally gorgeous actress of her era (hello, Vivien Leigh!), but she sure could act her way out of a thousand wet paper bags.

by Jennifer Percy

Part memoir, part investigative journalism, Demon Camp tells the troubling story of a soldier named Caleb Daniels who turns to a "Christian exorcism camp" in Georgia as a way of getting rid of "the Black Thing" which has plagued him since his return from Afghanistan after a Chinook helicopter carrying sixteen Special Ops soldiers crashes during a rescue mission, killing everyone on board, including Caleb's best friend Kip Jacoby. Back stateside, Caleb begins to see dead soldiers everywhere and is convinced he's been possessed by a demon. To rid himself of these apparitions, he decides to kill himself...but veers off instead into the company of the bizzaro camp in rural Georgia. At this point, Jennifer Percy, gathering notes for a story about soldiers suffering from PTSD, gets personally involved in Caleb's life. That's when things get really interesting. In her debut, Percy has delivered a book that's haunting, empathetic, and crackling with beautiful sentences. Demon Camp reads like a fevered dream and, if you're like me, it will stay with you for a long, long time after you turn the final page.

by Malcolm Brooks

This was the year for Montana novelists and Malcolm Brooks' debut was among the best of them. (Full disclosure: Malcolm lives just up the road from me and we've become good friends...but only after I finished reading Painted Horses, so I think my initial assessment is still relatively untainted.) Set in the Big Sky state in the mid-1950s, Painted Horses gives us an American West on the cusp of change. Catherine Lemay is a young archaeologist hired to survey a canyon in advance of a major dam project; her job is to make sure nothing of historic value will be lost in the coming flood—a task that proves to be more complicated than she thought after she meets John H, a mustanger and a veteran of the U.S. Army’s last mounted cavalry campaign, who’s been living a fugitive life in the canyon. Together, the two race against time to save the past before it is destroyed by an industry with an eye on the future. Painted Horses is unlike any “western” I’ve read; it refreshes the genre while nodding back at its roots. This novel should already be at the top of the list for Larry McMurtry Fan Club members.

by Josh Weil

Josh Weil's first full-length novel The Great Glass Sea, long-awaited after his debut collection of novellas The New Valley, is many things (apart from being great indeed). It's about a giant greenhouse, mirrors floating in space, sibling rivalry, and a Russia unlike the one we know. It is a story about the complicated love between brothers. It is a multi-genre novel that takes meaty bites of science-fiction, fantasy, magical realism, and big Russian books by the likes of Tolstoy, Dostoevsky and Solzhenitsyn. It is a superb meditation on individualism and the cost of courage. It is a book with a chapter ("Heaven's Breast") which contains some of the most breath-taking imagery of ANY book I read in the past five years (I'd quote the entire chapter here if I could, but I can't, so you'll just have to go out and buy the book for yourself to experience the beauty for yourself). And The Great Glass Sea is a book rife with beautiful sentences like these: "He breathed in. If there was a faint redolence of mushroom and cigarettes and something fresh and sharp as a radish newly bit, on her it still seemed unlike anything he'd ever known." And, "Nothing bold was ever built without someone deciding where to lay the first stone." Or, "And the hail spilled down, a ceaseless clattering of pearls stripped off a broken string wrapped round and round the welkin neck, each one a whisper through the clouds, a multitude of last prayers mouthed, until the final stone slipped off the necklace end and down the breast of heaven and left the clouds all hushed." The Great Glass Sea is a big book of 400 pages, but I found myself taking it slow, savoring the many delicious lines along the way to its wholly-satisfying finish.

by Cara Hoffman

In Cara Hoffman's riveting novel, Lauren Clay has returned from a tour of duty in Iraq in time to spend Christmas holiday with her father and younger brother Danny. All seems fine on the surface, but—as with Caleb Daniels in Demon Camp—there are some rough seas building inside Lauren. Be Safe I Love You is populated with engaging characters and carries an urgent message about how we treat our veterans returning from war. I also appreciated Cara Hoffman's exceptional novel for the way it portrayed female soldiers--characters of whom we see far too little in contemporary fiction.

by Bill Roorbach

When I think back to everything I read in 2014, Bill Roorbach's novel takes the prize for Book Which Most Bruised Strangers' Palms After I Shoved It Into Their Hands. The Remedy for Love is definitely a "You must read this!" kind of book. Here's a pithy plot synopsis (which is actually the blurby words of praise I gave the novel after reading an advance copy): Take two strangers—Eric, a small-town lawyer, and Danielle, a former schoolteacher turned homeless squatter—put them in a cabin in the Maine woods, spice it up with a little romantic tension, stir in the wreckage of past love affairs, sprinkle liberally with sharp, funny dialogue, then add the Storm of the Century which buries the cabin in huge drifts of snow, and—voila!—you've got The Remedy for Love, one of the best novels of this or any year. I'm not a doctor, but I'll be prescribing Bill Roorbach's novel to readers sick of blase, cliched love stories that follow worn-out formulas. What we have here is a flat-out funny, sexy, and poignant romantic thriller. The Remedy for Love is good medicine which most readers will want to swallow in one dose. I don't, however, have a remedy for those bruises on your hands. Sorry about that.

by Phil Klay

Believe everything you've heard about this book--it deserves every syllable of praise! Phil Klay's short stories put the Iraq War and its lingering after-taste right in our laps—which is exactly where the war needs to be. Want to know what it was really like to fight a troubling, complicated war? Read these stories and you'll be there in the sand with Klay's characters. This fiction, true as anything else you'll read, penetrates to the heart of what it's like to serve on a modern-day battlefield (both overseas and back here in America). Unflinchingly honest, these stories never blink. It's no hyperbole to say the Iraq War has finally found its voice.

by Elizabeth McCracken

Sentence-for-sentence, Elizabeth McCracken’s new collection of short stories (her first since 1993’s Here’s Your Hat What’s Your Hurry) is the best value for lovers of fine, funny writing. I can't tell you how many times I chuckled (and, on occasion, let go into a barking, clear-the-room peal of laughter) while making my way through these stories. That's all well and good, but McCracken can also break the reader's heart--see, for example, the title story in which a family's trip to Paris is interrupted by their rebellious daughter's risky behavior; or “Peter Elroy: A Documentary by Ian Casey” where the now-dying subject of the documentary tries to turn the tables on the filmmaker years after their relationship was ruptured by betrayal. Thunderstruck was the one book I read this year which brought me equal doses of joy and sadness. I loved every minute of it.

by Lydia Netzer

One of the smartest books I've ever read about the hazards of parenting in the Golden Age of Facebook is, predictably enough, only available as an e-book. You shouldn't let that stop you from downloading Lydia Netzer's wickedly funny novella Everybody's Baby and reading it on whatever platform you choose. Just have plenty of screen wipes handy to clean up your laugh-spittle. A tall, curly-haired Scot, Billy Bream is the expectant father in Everybody's Baby who just can't stay off his laptop and tablet--even as his wife, Jenna, is screaming through her labor pains in the delivery room. Admit it: we all have a touch of the Billy in us. However, obsessively checking our social media feeds is where most of us stop. Billy and Jenna take it two or three steps further by engaging a little too much with the online community. Everybody's Baby turns into a cautionary tale for our times--a clever morality play where God is not just some deus ex machina flying in on pulleys and wires in the Third Act, but is really in the machine. Jenna and Billy decide to pay for their baby by crowd-sourcing bits of the infant to strangers on the internet. Every Kickstarter comes with perks, but in the case of "everybody's baby," those benefits turn into something that is, at heart, rather terrifying--things like: for $10, "You receive an invitation to appear waving in a crowd, captured on film for a segment in the baby’s first birthday video," or, for $30, "You can rub the pregnant belly, at a designated belly-rubbing station, on a designated rubbing day, to be determined," or, for $300, you can "Take home the placenta to do with as you will." The problems Billy and Jenna face aren't the typical challenges of first-time parents, but they are fears which most of us have faced at one point or another: How much is too much? How do we retain our identity in an increasingly-homogenized, flat-lined electronic world? Where do we draw the boundaries of privacy? This extends far beyond the screens on our electronic devices. Even if you're not sharing kitten-and-dolphin videos on Facebook, chances are that someone in the grocery line has stood too close to you, poked you with a personal question, or asked to rub your pregnant belly. For a longer treatment of modern romance (also available in the "dead-tree" print format) I also highly recommend Netzer's other 2014 novel, How to Tell Toledo From the Night Sky. Both books are sheer delights.

by Roxane Gay

There are books you read, and then there are books which read you--the ones that go deep inside, each word a tiny mirror forcing you to question who you are and how you see the world. Roxane Gay's debut novel is one of those books. It is horrific, it is beautiful, it is uncompromising. An Untamed State opens with the dissolution of a fairy tale. Haitian-American Mireille Duval Jameson, daughter of one of the most powerful men of Port-au-Prince, is abducted while on vacation visiting her family. Gay gets right down to it with the novel's first sentence: "Once upon a time, in a far-off land, I was kidnapped by a gang of fearless yet terrified young men with so much impossible hope beating inside their bodies it burned their very skin and strengthened their will right through their bones." From that impossible-to-put-down opening chapter, we follow Mireille's captivity, blow by blow. The chapter headings resemble stick numbers a prisoner might scratch on a wall and we are there with Mireille, chained to a bed as she is tortured and repeatedly raped, the kidnapping stretching to unendurable lengths when her wealthy father refuses to pay the ransom. An Untamed State is a difficult book to read--those little word-mirrors burn, burn, burn--but once begun, it's nearly impossible to stop. "When I closed my eyes, I was no one," Mireille says. "I was the woman who forced herself to forget her husband, her child, all the joy she had ever known, who carefully stripped herself of her memories so she could survive." Narratively-speaking, I'm in awe of what Gay has done here--especially when, midway through the novel, gears shift and it becomes a no-less-tense account of healing, recovery and the hard, seemingly-impossible journey toward hope--which, fittingly, is literally the final word of the novel.

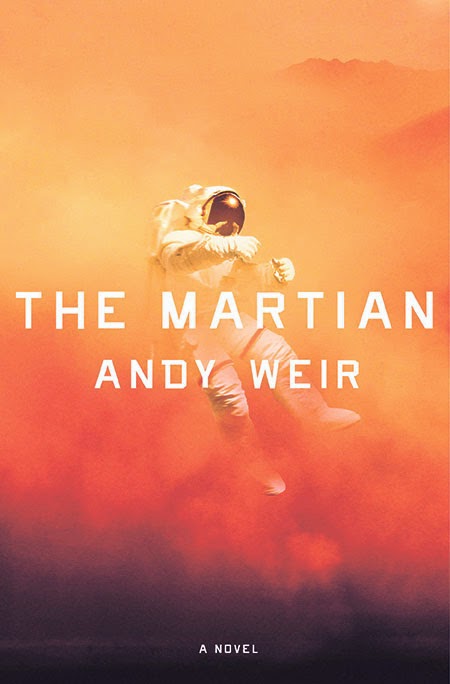

by Andy Weir

This science-fiction novel may be the most imperfect book on this list--some of the dialogue feels like it's cut-and-pasted from the lamest summer blockbuster movie and there are stretches where the science gets too heavy and I longed for more fiction--but The Martian was also the one I. Couldn't. Put. Down. Combining the best elements of Robinson Crusoe and the movies Castaway and Apollo 13, this is the white-knuckle read of the year. Author Andy Weir's forte is the plot hook: a geeky scientist on a mission to Mars gets stranded after a dust storm forces a hasty evacuation by his shipmates. When his fellow astronauts rocket off the planet without him (sort of a galactic Home Alone Moment), Mark Watney is left to fend for himself with very little food, dwindling batteries and zero communication with Earth. His ingenuity in building a livable shelter, creating soil to grow potatoes, and jury-rigging a rover to travel across the planet is breath-taking and inspiring.

by Kim Zupan

On the surface, there’s not a lot of action in Kim Zupan’s debut novel: some shallow graves are dug, a sheriff’s deputy goes out with his dog to look for missing persons, and there’s one particularly harrowing chase through a field in a Montana prairie. Other than that, most of the “action” takes place in the lush language which fills the pages of The Ploughmen–primarily the late-night conversations between John Gload, a septuagenarian serial killer, and Valentine Millimaki, the aforementioned sheriff’s deputy who works the graveyard shift at the Copper County jail. As the book’s jacket copy explains, “With a disintegrating marriage further collapsing under the strain of his night duty, Millimaki finds himself seeking counsel from a man whose troubled past shares something essential with his own.” Most of the book consists of cat-and-mouse conversations between diabolical killer and sympathetic lawman (very Silence of the Lambs-ian), and I’ve gotta say, I was held spellbound for the entire 256 pages of the novel. Zupan spins his tale with sentences that are rich in imagery and complex in construction. This is a book which encourages readers to slow down and savor its near-poetic language. At the same time, Zupan ratchets up the suspense with a menacing undertow that pulled me deeper and deeper into the novel.

by Raina Telgemeier

I will always remember 2014 as the year I discovered my new Author BFF. Included in the candy-colored pages of The Best American Comics 2014 was an excerpt from Raina Telgemeier's graphic novel Drama. I was quickly drawn in (pardon the pun) by Telgemeier's terrific pen work which combines realism with occasional cartoon-y flourishes (she cites Hi and Lois as one of her influences, and it's easy to see traces of that classic comic strip in the curves and lines of her characters). Drama is about the trials and tribulations of Callie and her junior-high friends as they rehearse for an upcoming school play. Telgemeier brilliantly captures what it's like to be young, in love, and ripe for public humiliation. I could totally relate. In fact, I loved the excerpt from Drama so much, I immediately went out and bought it and Telgemeier's other books: Sisters and Smile (her best work to date). I loved all of Telgemeier's Young Adult novels, but since this is about 2014, I'll say a few words on behalf of this year's Sisters. Like Smile, it's largely (if not wholly) autobiographical and, as you might expect, centers around the sibling rivalry between Raina and her younger sister Amara. The main narrative of Sisters revolves around a car trip from their home in San Francisco to a family reunion in Colorado, with flashbacks illuminating the dynamics between the characters. In addition to the squabbling between the sisters (and the mutual endurance tests a younger brother brings their way), the story also adds some heavier adult themes as, on the periphery, we see growing cracks in their parents' relationship. This lends the book an unexpected poignancy and realism. Though it may seem that Telgemeier's books are geared toward middle-grade readers (especially girls), I'm here to tell you that this middle-aged, greying man thoroughly enjoyed every hand-drawn panel of Telgemeier's graphic novel.

by Jenny Offill

I finished out this year by finally succumbing to the battering-ram of praise for Jenny Offill's slim, sharp novel about a marriage beset by the pressures of parenthood and infidelity. As it turns out, all those other yea-sayers knew what they were talking about. Dept. of Speculation came at me like a bullet train whispering along the tracks--nearly silent in its approach, but tearing me limb from limb when it finally hit. It is a book which can be read in a single sitting (though I took three or four) and it welcomes--almost demands--an immediate re-read. The language has been honed and distilled to a purity not often found in contemporary writing. Dept. of Speculation makes its strongest mark at the individual sentence level ("The baby's eyes were dark, almost black, and when I nursed her in the middle of the night, she'd stare at me with a stunned, shipwrecked look as if my body were the island she'd washed up on." Or, "A dog runs through the field, his dark fur ruffled with light."), but it's only when I finished the novel that I was able to appreciate the totality of its impact. It's a jigsaw puzzle whose 1,000 pieces interlock perfectly.