Front Porch Books is a monthly tally of books--mainly advance review copies (aka "uncorrected proofs" and "galleys")--I've received from publishers, but also sprinkled with packages from Book Mooch, Amazon and other sources. Because my dear friends, Mr. FedEx and Mrs. UPS, leave them with a doorbell-and-dash method of delivery, I call them my Front Porch Books. In this digital age, ARCs are also beamed to the doorstep of my Kindle via NetGalley and Edelweiss. Note: most of these books won't be released for another 2-6 months; I'm just here to pique your interest and stock your wish lists. Cover art and opening lines may change before the book is finally released.

Little Century by Anna Keesey (Farrar Straus Giroux): One look at the cover of Anna Keesey's debut novel and two things come to mind: Buffalo Bill and Larry McMurtry. As it turns out, neither are too far off the mark. Oh, it may not have the showmanship of B. B. or the epic length of Lonesome Dove, but Little Century has enough going for it to make me put it near the top of my To-Be-Read pile. Here's the Jacket Copy:

Orphaned after the death of her mother, eighteen-year-old Esther Chambers heads west in search of her only living relative. In the lawless frontier town of Century, Oregon, she’s met by her distant cousin, a laconic cattle rancher named Ferris Pickett. Pick leads her to a tiny cabin by a small lake called Half-a-Mind, and there she begins her new life as a homesteader. If she can hold out for five years, the land will join Pick’s already impressive spread. But Esther discovers that this town on the edge of civilization is in the midst of a range war. There’s plenty of land, but somehow it is not enough for the ranchers—it’s cattle against sheep, with water at a premium. In this charged climate, small incidents of violence swiftly escalate, and Esther finds her sympathies divided between her cousin and a sheepherder named Ben Cruff, a sworn enemy of the cattle ranchers. As her feelings for Ben and for her land grow, she begins to see she can’t be loyal to both.Blurbworthiness: ''Here is a fine novel, written with grace, about the settling of Oregon and the evening redness in the West. In the desert town of Century, haunted by Indian blood and barren to the core, the cattlemen hate the shepherds and the shepherds hate the cattlemen. But as the community is about to consume itself with greed and vengeance, a young orphan from Chicago shows up with a moral clarity that outstrips her age, to remind us that character matters and that justice is pursuant to conscience. Little Century is a frontier saga, a love story, and an epic of many small pleasures.'' (Joshua Ferris, author of Then We Came to the End)

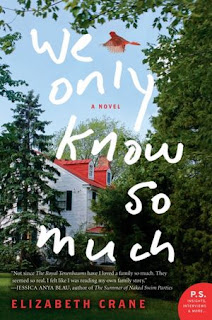

We Only Know So Much by Elizabeth Crane (Harper Perennial): This novel wins the award for Most Arresting Voice out of all the books to land on my front porch this past month. I'll just give it to you like a tumblerful of whiskey--neat, no rocks:

At the moment, the Copeland family is a bit at odds.And with that, a TBR-pile resident is born. I don't know about you, but I definitely get a Franzenesque vibe from these first few pages--which, I should add, is meant as a compliment. Here's the Jacket Copy to offer more evidence why you should add We Only Know So Much to your must-read list this summer:

First of all, Priscilla is a bitch. Or at least a brat. An extreme brat. Look, we're just reporting what we've heard. Maybe bitch is too harsh. Let's say it this way: her attitude is often poor. The reasons are currently unclear. For one thing, her parents might have done better to rethink that name. Right? It's not very contemporary. Something about it's just bitchy-sounding. Maybe she knew that when she was little. She's been this way since she was born and she's nineteen now and it's only gotten worse. What are you supposed to do when your daughter's like this? No one wants to believe their own kid isn't the nicest person, but think about it, girls like this aren't born in a void. Jean and her husband, Gordon, have punished her, of course, told her no, admonished her, this sort of thing, but nothing's worked. They've come to think it's just innate. That may or may not be true. Maybe she got it from her great-grandmother. Genetically or otherwise. Just a thought. And Priscilla's like this everywhere. At home, at work, at school, everywhere. Let's hope that if you're a waiter she never sits at your table. If she sits at your table she will be sending some shit back, and if you do that waiter thing where you introduce yourself, you will rue that choice because she will use your name so many times that by the time she leaves you will want to change it. Jean and Gordon almost never take her to restaurants anymore. Dinner at home is tough enough.

Jean Copeland, an emotionally withdrawn wife and mother of two, has taken a secret lover—only to lose him in a moment of tragedy that leaves her reeling. Her husband, Gordon, is oblivious, distracted by the fear that he's losing his most prized asset: his memory. Daughter Priscilla (a pill since birth—don't get us started) is talking about clothes, or TV, or whatever, and hatching a plan to extend her maddening reach to all of America. Nine-year-old Otis is torn between his two greatest loves: crossword puzzles and his new girlfriend. At the back of the house, grandfather Theodore is in the early throes of Parkinson's disease. (And he's fine with it—as long as they continue to let him walk the damn dog alone.) And Vivian, the family's ninety-eight-year-old matriarch, is a razor-sharp grande dame who suffers no fools...and still harbors secret dreams of her own. With empathy, humor, and an unforgettable voice, Elizabeth Crane reveals what one family finds when everyone goes looking for meaning in all the wrong places.Blurbworthiness: “The beauty in Crane’s novel is her sweep from acid commentary to heartfelt portrayal of real-life loves and losses.” (Kirkus Reviews)

Wild Delicate Seconds: 29 Wildlife Encounters by Charles Finn (Oregon State University Press): I first became aware of Charles Finn's slender, meditative book when he swept through Montana on a reading tour. Unfortunately, I didn't get the chance to attend one of those readings (when it comes to book tours, Butte is almost always bypassed and overlooked--a gas-stop along the interstate, at best). But now I've got his book in my hand and I have to say, it's a thing of beauty--like holding an edelweiss flower against the back-light of the sun, or cupping a downy-feathered fledgling in my palm. Here's how Finn describes his book in the Preface:

What follow are twenty-nine nonfiction micro-essays, each one a description of a chance encounter I had with a member (or members) of the fraternity of wildlife that call the Pacific Northwest home....It's no surprise that over the years my journals have filled with descriptions of black bears and bumble bees, mountain lions and muskrats, elk, pygmy owls, ravens and flying squirrels. What follows are those stories. With the exception of the snowy owls, sandhill cranes, and golden eagles, which I specifically went to see, all of these encounters were complete surprises: as I came inside from chopping wood a red-shafted flicker flapped against my cabin window; as I rested in the shade by a river a red fox suddenly appeared trotting toward me; lost, driving to a new job, and coming up over a small rise, I saw a hundred bison on the slope below me, their unmatched authority haloing them in the morning sun. Because of the unexpectedness of these meeting they held a special quality for me. Always there was a timelessness, a residue of the sacred, and a lingering feeling that I was witnessing something spectacular. And I was. Because these encounters were often so brief (usually just a matter of minutes, sometimes seconds) it seemed appropriate that I kept my accounting of them equally concise too.....in this way only the most important details survive, those few shimmering moments I spent lost to the world, alive in the company of these "other nations," as Henry Beston describes them, the wild, feathered, and furred creatures we share this planet with. Finally, I must note that there is very little adrenaline here. There are no maulings. No narrow escapes. It is not that kind of book. Instead, it is a quiet book made up of quiet moments that any of us might have....And here's the first paragraph from the first wild encounter in the book ("Black Bear"), which gives you a sense of the lyricism flooding Finn's pages:

Bear. It's a big word. Say it in casual conversation and people halfway across the room will stop and cock an ear, setting their drink down or halting a fork in mid-air. Everyone wants to talk about them and everyone wants to see one. They are the denizens of our forests. They have myopic, grandfatherly eyes, bionic noses, and half-dome cartoon ears. Their can-opener claws resemble hay rakes and when they exhale it's with a fetid, composted air. Born in the dead of winter they are blind as new kittens, no bigger than shoes, pink as a ribbon you might win at a fair, nuzzling their mother until the rich milk river flows.

Here Lies Hugh Glass: A Mountain Man, a Bear, and the Rise of the American Nation by Jon T. Coleman (Hill and Wang): Hugh Glass' encounter with a grizzly in 1823 wasn't as delicate or pleasant as Finn's moments with wildlife. If you didn't grow up in the Rocky Mountain West (as I did), you might not be familiar with the gory legend of Hugh Glass. Once you've heard the story, however, you won't soon forget it. Here, I'll let Professor Coleman describe it in his introduction to this book:

Hugh Glass nearly ended his days as meat. In August 1823, a female grizzly bear attacked him. She caught him as he scrambled up a tree, slicing a gash with a fore-claw from scalp to hamstring. She bit his head, punctured his throat, and ripped a hunk from his rear. The bear tore him "nearly to peases," and actually swallowed a few mouthfuls before Glass's associates shot and killed her. Expecting his hunter to die soon, Colonel Andrew Henry bribed two men to wait and bury the body. The expedition traveled on, and after six days the death watchers left, too, abandoning their comrade, who was still sucking breaths through a punctured trachea. Unable to walk, subsisting on insects, snakes, and carrion, an enraged Glass crawled and hiked two hundred miles to Fort Kiowa to kill those who had left him to die.Source material was undoubtedly scant and often unreliable, but as you can see, Coleman puts hair on the chest of the myth. Here's more from the Jacket Copy:

The acclaimed historian Jon T. Coleman delves into the accounts left by Glass’s contemporaries and the mythologizers who used his story to advance their literary and filmmaking careers. A spectacle of grit in the face of overwhelming odds, Glass sold copy and tickets. But he did much more. Through him, the grievances and frustrations of hired hunters in the early American West and the natural world they traversed and explored bled into the narrative of the nation. A marginal player who nonetheless sheds light on the terrifying drama of life on the frontier, Glass endures as a consummate survivor and a complex example of American manhood.

The Girl Giant by Kristen den Hartog (Simon and Schuster): I'm a huge fan of The Giant's House by Elizabeth McCracken, as well as The Time Traveler's Wife, A Prayer for Owen Meany and any number of other novels featured quirky, potentially-doomed characters who observe our society from the fringes. So, Kristen den Hartog's new novel should be a good fit for my offbeat tastes. Here's the Jacket Copy:

Ruth Brennan is a giant, “a rare, organic blunder pressed into a dollhouse world,” as she calls herself. Growing up in a small town, where even an ordinary person can’t simply fade into the background, there is no hiding the fact that Ruth is different: she can see it in the eyes of everyone around her, even her own parents. James and Elspeth Brennan are emotionally at sea, struggling with the devastation wrought on their lives by World War II and with their unspoken terror that the daughter they love may, like so much else, one day be taken away from them. But fate works in strange ways, and Ruth finds that for all the things that go unsaid around her, she is nonetheless able to see deeply into the secret hearts of others—their past traumas, their present fears, and the people they might become, if only they have courage enough.One other thing to note: The Girl Giant is packaged in a smallish trade paperback edition by Simon and Schuster. An ironic gesture, I'm sure--"Read about a giant in a book you can hold in the palm of your hand!"--but it's such a handsome little volume that I'm willing to overlook the obvious.

The Watch by Joydeep Roy-Bhattacharya (Hogarth): I've been immersed in contemporary war literature lately (Kaboom: Embracing the Suck in a Savage Little War by Matt Gallagher, Dust to Dust: A Memoir by Benjamin Busch, Billy Lynn's Long Halftime Walk by Ben Fountain, and The Yellow Birds by Kevin Powers), but here's a novel that has a little different slant on modern combat--it puts us on the other side of the concertina wire ringing the American compounds in Iraq and Afghanistan. The Watch takes the classic story of Antigone and puts in the tense, frightening setting of sand, heat and hair-trigger nerves. The Jacket Copy explains:

Following a desperate night-long battle, a group of beleaguered soldiers in an isolated base in Kandahar are faced with a lone woman demanding the return of her brother’s body. Is she a spy, a black widow, a lunatic, or is she what she claims to be: a grieving young sister intent on burying her brother according to local rites? Single-minded in her mission, she refuses to move from her spot on the field in full view of every soldier in the stark outpost. Her presence quickly proves dangerous as the camp’s tense, claustrophobic atmosphere comes to a boil when the men begin arguing about what to do next. Joydeep Roy-Bhattacharya’s heartbreaking and haunting novel, The Watch, takes a timeless tragedy and hurls it into present-day Afghanistan. Taking its cues from the Antigone myth, Roy-Bhattacharya brilliantly recreates the chaos, intensity, and immediacy of battle, and conveys the inevitable repercussions felt by the soldiers, their families, and by one sister. The result is a gripping tour through the reality of this very contemporary conflict, and our most powerful expression to date of the nature and futility of war.Blurbworthiness: “We watch as the resistance of an isolated American garrison in Afghanistan is ground down, not by force of arms but by the will of a single unarmed woman, holding inflexibly to an idea of what is just and right.” (J. M. Coetzee, author of Disgrace)

Brand New Human Being by Emily Jeanne Miller (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt): Miller's debut novel has Hollywood written all over it, starting with these classic Opening Lines: "My name is Logan Pyle. My father is dead, my wife is indifferent, and my son is strange. I’m thirty-six years old. My life is nothing like I thought it would be." Can't you just hear someone like John Cusack narrating that as the camera tracks along an autumn-leaf-strewn street in a small Montana town? Miller started writing her fiction when she was living in Missoula while getting a Master's degree in Environmental Studies so there's plenty of verisimilitude at work here. Though her setting has been fictionalized, there's enough crisp mountain air blowing through her sentences to call northwestern Montana to mind. Here's the Jacket Copy to fill us in on the story of Brand New Human Being:

Meet Logan Pyle, a lapsed grad student and stay-at-home dad who’s holding it together by a thread. His father, Gus, has died; his wife, Julie, has grown distant; his four-year-old son has gone back to drinking from a bottle. When he finds Julie kissing another man on a pile of coats at a party, the thread snaps. Logan packs a bag, buckles his son into his car seat, and heads north with a 1930s Louisville Slugger in the back of his truck, a maxed-out credit card in his wallet, and revenge in his heart. After some bad decisions and worse luck, he lands at his father’s old A-frame cabin, where his father’s young widow, Bennie, now lives. She has every reason to turn Logan away, but when she doesn’t, she opens the door to unexpected redemption—for both of them.

Walt Disney's Uncle Scrooge: "Only a Poor Old Man" (Vol. 1) by Carl Barks (Fantagraphics Books): Surely I'm not the only kid in America who went through a phase of saying everything in a Donald Duck voice--a speech impediment that involved rattling a considerable amount of spittle between one's jaw and cheek. Though I was a rank amateur compared to the late great Clarence Nash, there was still something satisfying about sitting around the dinner table and asking my mother to pass the mashed potatoes in a blustery hissing voice which, in hindsight, probably sounded more like I was coughing up a loogey than it did Donald Duck's voice. Oh well, it still quacked her up every time. You know what else is completely quackers? The fact that such a short-tempered, preening duck in a sailor suit could have such a rich, worldly uncle who, as the cover of Fantagraphics' new release reminds us, spent the majority of his time swan-diving (duck-diving?) into heaps of gold coins. If Donald Duck was the sassy hero of our childhood days, then Uncle Scrooge was the adult duck we all aspired to be. I mean, who wouldn't want to have a fortune of one multiplujillion, nine obsaquatumatillion, six hundred and twenty-three dollars and sixty-two cents? The miserly misanthropic moneymaker was created by Carl Barks in 1947 for a Donald Duck comic, "Christmas on Bear Mountain" published by Dell Comics. In time, Unca Scrooge went on to have his own series of comic books, which Fantagraphics presents in this volume with their typical finesse and color-popping beauty. Starting with "Only a Poor Old Man," the book takes us through more than two dozen classic Scrooge McDuck tales in which fortunes are lost, fortunes are gained, and eyes go ka-ching! with dollar signs. In his Introduction, George Lucas writes: "I think the reason Carl Barks's stories have endured and have had such international appeal is primarily their strength as good stories. Yet on a deeper level, they display American characteristics that are readily recognizable to the reader: ingenuity, integrity, determination, a kind of benign avarice, boldness, a love of adventure, and a sense of humor."

The Pleasures of Men by Kate Williams (Hyperion): This debut novel, set in Victorian London, joins a long list of my favorite novels like The Crimson Petal and the White, The Dress Lodger, and of course just about any Dickens narrative you could name. The Pleasures of Men is narrated by a nineteen-year-old girl who becomes obsessed with a series of murders that are ravaging the underbelly of London. As Catherine Sorgeiul is pulled deeper into the underworld, the serial killer is drawn closer and closer to her. On the surface, the plot sounds like it could be surgically transplanted into any number of other novels on the new-release tables these days, but what really grabbed me here were the Opening Lines. With your indulgence, I'll give you the entire first scene of the novel in all its grisly, grimy, gruesome glory:

Night comes late to Spitalfields Market, across the dump at the back used by the traders for the detritus of old vegetables and splintered crates. The stall holders pack up their apples and cabbages, gather their pieces of meat, oysters and bags of fish, the battered hardware and cheap clothes, down the last dregs of ale, then wrap their arms around each other for the short journey to the lights of Lely’s gin house on the corner. I stay behind, near the dump, see the mass glistening as maggots slither out of the soft flesh of the discarded beef.

The first scavengers are the younger men, dismissed soldiers hiking useless legs, crawling up the dump and delving in their hands. Then women, babies swaddled to their breasts, picking off the heads from trout and cockerels and pulling scraps of pork from the bones. Huddles of rheumy children come next, biting off carrot tops and around potato eyes, licking at the old boxes, rubbing their feet in the last juice of the meat. And when all the others have departed, the old woman comes, baring her rotted teeth at the pile, her lifeless bosoms like dirty moons, pulling herself around the sides of the stack, racking herself with laughter.

At first, when she screams, no one hears but me. Not the seamen outside the gin shop, talking about money and girls, or the women in darkened red dresses and thin shawls, waiting along street corners, or even the scavenging children, fighting over their spoils in the corner of the marketplace. She does not stop. The sound hurtles over the walls until they seem to echo to her cries and so the children look up and the women hear, and the sailors put aside their bottles and soon real men come, significant, responsible men with dressed hair and long black cloaks, who never give those who work in the market or the scavengers a single thought. They look at the madwoman, rocking in the blood, and think that she is the one dying.

Then they see what lies behind her. A girl, her blue dress ragged ribbons around her legs. She has been stabbed twenty times, they guess, over and over until her skin lies like ruffled feathers over the darkening flesh. Her arms and legs have been bent back so she is all chest, and her pale hair has been plaited and thrust into her mouth. A blue ribbon and a feathered comb cling to the edges of her hair. Over what remains of her bosom, the killer has gouged a deep star. And then they peer further and see a one-pence coin, perched on the still warm core of her heart.

The Secret Life of Objects by Dawn Raffel (Jaded Ibis Press): I'll confess that when I first picked up Raffel's book, I thought it was a collection of short stories. The front and back covers on my advance reading copy were no help in telling me what the book was about--it was an object that held its own secrets, it seemed. It only took me a few pages to realize that what I held in my hands was a unique, evocative memoir, told in a series of short micro-essays. Raffel is the author of two short-story collections (Further Adventures in the Restless Universe and In The Year Of The Long Division) and a novel (Carrying the Body) and this short memoir is written with all the wild bloom of imagination that fiction brings to the table. As she says early in the book, "All memoir is fiction." The Secret Life of Objects tells the story of Raffel's family in vignettes about material possessions, starting with a coffee mug she finds when going through her mother's belongings after that woman's sudden death. It's an interesting way to tell a life story: we are what we own. In Raffel's case, a tea set can spiral her off into a memory of her father with his whistling hearing aid, or a dress will remind her of the summer of 1984, holding in its weave "the heat, my young body, the necklace--all hearts--that I wore with it that broke, our rooftop in twilight, the city below us, the promise of the life I planned to live." Blurbworthiness: "'Sometimes things shatter,' writes Dawn Raffel in The Secret Life of Objects. 'More often they just fade.' But in this evocative memoir, moments from the past do not fade--they breathe on the page, rendering a striking portrait of a woman through her connections to the people she's loved, the places she been, what’s been lost, and what remains. In clear, beautiful prose Raffel reveals the haunting qualities of the objects we gather, as well as the sustaining and elusive nature of memory itself." (Samuel Ligon, author of Drift and Swerve)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.